In Telemachus Stephen says to Mulligan, "You saved

men from drowning. I'm not a hero, however." In Eumaeus

Bloom thinks of Mulligan's "rescue of that man from certain

drowning by artificial respiration and what they call first

aid at Skerries, or Malahide

was it?" Drawing on a real-life difference between Joyce and Oliver Gogarty, the novel

returns repeatedly to the theme of saving someone's life,

beginning with Stephen's meditations in Proteus on

whether he could ever be capable of such a thing: "He saved

men from drowning and you shake at a cur's yelping.... Would

you do what he did? A boat would be near, a

lifebuoy. Natürlich, put there for you. Would you or

would you not?"

Gogarty did in fact save men from drowning, snatching people

from the Liffey at least four times between 1898 and 1901, and

his aquatic heroism outlived his twenties. In November 1922,

the commander of an IRA faction that opposed the Treaty

between Ireland and Great Britain authorized the killing of

Irish Free State Senators, of whom Gogarty was one. Two months

later he was kidnapped by IRA soldiers and held in a house

near Chapelizod. Aware that he might soon be executed, he

feigned diarrhea, was led out into the garden, broke free,

jumped into the Liffey, and swam to freedom in Phoenix Park.

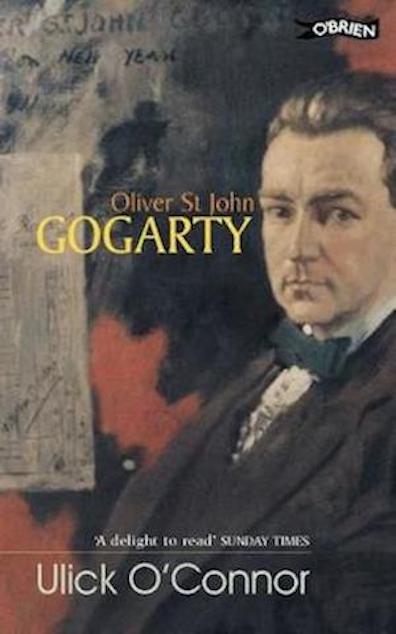

Ulick O’Connor's authorized, and valuable, biography of

Gogarty details these events beginning on p. 194.

Ulysses continues to follow the thread of aquatic

heroism, but subsequent instances are tinged with sardonic

irony. In Hades we learn that the son of Reuben J.

Dodd jumped into the Liffey, probably in an attempt at

suicide, and was hooked out by a boatman. Dodd rewarded the

rescuer “like a hero,” with the

un-princely sum of a florin

(two shillings). Hearing the story, Simon Dedalus remarks

“drily” that it was “One and

eightpence too much.”

In Wandering Rocks Lenehan alludes to the story of

Tom Rochford going down into a sewer to rescue a man overcome

by gas. “’He’s a hero,’ he said simply. . . . ‘The act of a

hero.’” In this instance, however, life complicates the

simplicity of art. Robert Martin Adams describes how twelve

men in succession went down the manhole, one after another

becoming overcome by the methane and requiring a new rescuer

to enter the fray (Surface and Symbol, 92-93). Tom

Rochford was merely the third in this series of comically

futile heroic actors, but Joyce knew and liked Rochford and

decided to elevate his importance.

In Circe, the importance is inflated to absurd

proportions, as Rochford, Christ-like, jumps in to save the

dead (Paddy Dignam) rather than the dying. Paddy Dignam, who

has become a dog, worms his

way down through a hole in the ground, followed by “an obese

grandfather rat” like the tomb-diving one that Bloom sees in Hades.

Dignam’s voice is heard “baying under ground.” Tom Rochford,

following close behind, pauses to orate: “(A hand to his

breastbone, bows) Reuben J. A florin I find him. (He

fixes the manhole with a resolute stare) My turn now

on. Follow me up to Carlow. (He executes a daredevil

salmon leap in the air and is engulfed in the coalhole. . .

.)”