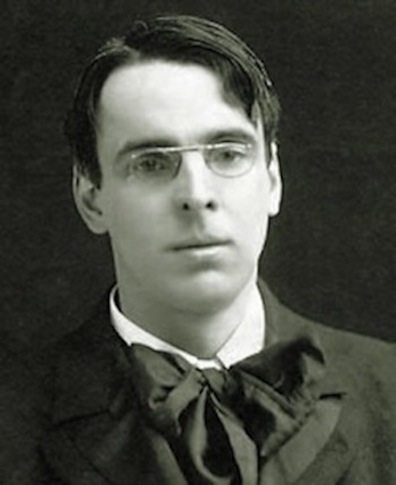

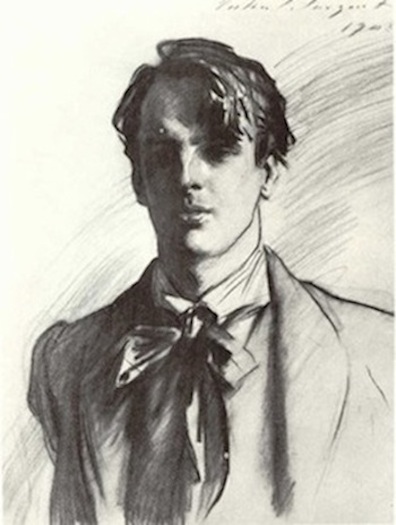

After Mulligan tells Stephen to "Give up the moody brooding"

about his mother's death, he quotes some apposite lines from a

song in W. B. Yeats' play The Countess Kathleen:

"And no more turn aside and brood / Upon love’s bitter

mystery." The song’s soothing images of shore and sea

underline the gesture that Mulligan has just made toward the

surrounding water: “Look at the sea. What does it care

about offences?" Within a few lines it becomes

clear that Stephen too knows the song well, but for him it

carries more troubling meanings in relation to his mother.

Kathleen (the spelling was changed to Cathleen

in later versions) was first published in 1892 and first

performed in 1899. Joyce attended the premiere. He did not

care either for the play's overtly political agenda or for the

political backlash against it (he refused to sign a student

petition objecting to its disrespect for Christian doctrine).

But, as Ellmann reports, he was deeply moved by the song; "its

feverish discontent and promise of carefree exile were to

enter his own thought, and not long afterwards he set the poem

to music and praised it as the best lyric in the world" (67).

The lyrics are sung to console the Countess, after she has

sold her soul to the devil to relieve her starving tenants:

Who will go drive with Fergus now,

And pierce the deep wood’s woven shade,

And dance upon the level shore?

Young man, lift up your russet brow,

And lift your tender eyelids, maid,

And brood on hopes and fears no more.

And no more turn aside and brood

Upon love’s bitter mystery;

For Fergus rules the brazen cars,

And rules the shadow of the wood,

And the white breast of the dim sea

And all disheveled wandering stars.

Stephen sang the song for his mother when she was dying, and

phrases from it hover in his thoughts now: “Woodshadows”

(in the following line of the novel) recalls Yeats’ “shadow of

the wood,” and “White breast of the dim sea”

(two lines after that) quotes from the song verbatim. Mulligan

hears the poem's promise of happy release, but Stephen attends

more to the anguished love that motivates the

Countess. He recalls that when he had finished singing

the song and playing its “long dark chords,” his mother “was

crying in her wretched bed” for “those words, Stephen:

love’s bitter mystery.” Love is a mystery which he has not begun to

fathom but must learn, as both she and he know. Against

Mulligan’s escape into hedonism, then, Stephen finds himself

pulled toward deeper emotional engagement.

As a figure of Christian piety, suffering, and martyrdom,

Stephen's mother fills

him with terror and guilt, and his brooding on her death

is certainly unhealthy. But like Kathleen she has known

the love that frees one from the tyranny of

egoism. (After her death the countess is redeemed and

ascends into heaven, because her apostasy sprang from generous

motives.) Stephen must brood on this mystery.