"To whom?... Ah, to be sure!... The islanders, Mulligan said

to Haines casually, speak frequently of the collector of

prepuces." Adopting the persona of an ethnographer detailing

the exotic cultural practices of his countrymen to a visiting

colleague, Mulligan explains their belief in a strange deity

who judges the loyalty of his followers by their willingness

to slice rings of skin off the genital organs of their infant

male offspring. Joyce no doubt wishes to offend Irish

Catholics, but he may also be setting his sights higher: on

the Holy Father and his conclave of cardinals in Rome.

In Ithaca, Stephen too thinks of circumcision,

while urinating with Bloom in Bloom’s back yard. Exposed

penises make the scientific Bloom think of issues like

“tumidity," "sanitariness," size, and hairiness, but they turn

Stephen’s mind to the circumcision of Jesus Christ, and

particularly to the question of “whether the divine

prepuce, the carnal bridal ring of the holy Roman catholic

apostolic church, conserved in Calcata, were deserving of

simple hyperduly or of the fourth degree of latria accorded

to the abscission of such divine excrescences as hair and

toenails.” Gifford glosses the question posed by

the dual nature of Christ: "is this relic a part of the body

of Jesus, in which case it is due latria, the highest kind of

worship, paid to God only . . . or is the relic 'human,' thus

meriting hyperdulia, the veneration given to the Virgin Mary

as the most exalted of human beings?" (586).

Christ’s foreskin, the only part of the divine body left

behind on earth (not counting hair, sloughed skin,

fingernails, and toenails), was indeed regarded not only as a

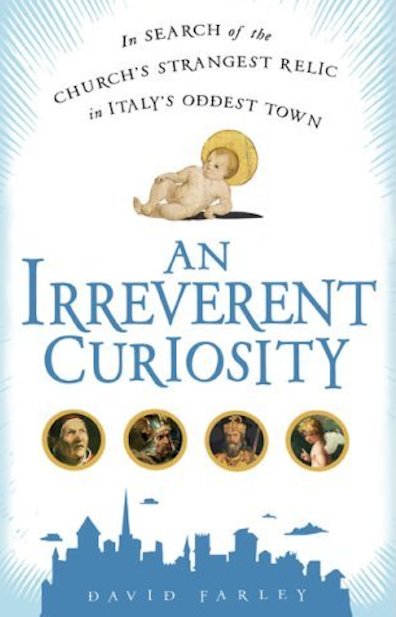

holy relic, but as a “carnal bridal ring.” A book by David

Farley, An Irreverent Curiosity: In Search of the

Church’s Strangest Relic in Italy’s Oddest Town (2009)

notes that Catherine of Siena, the medieval saint, was

reported to have worn her Lord’s foreskin as a ring around her

finger. In doing so she was probably following the practice of

many medieval female religious of becoming quite literally

married to Christ—a phenomenon explored in Sarah McNamer’s Affective

Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion

(2009). Later, though, the sacred penis part ended up in the

north Italian hill town of Calcata, making the town’s church

an important pilgrimage destination. Farley’s adventure story

starts from the fact that, in December 1983, the church’s

parish priest announced to his congregation that the foreskin

of Jesus had disappeared.

In addition to confirming what Stephen says about bridal

rings and about Calcata, Farley’s book discusses something

that is never mentioned in Ulysses but that may very

well account for Mulligan’s and Stephen’s strange

obsession. Although the divine foreskin had been an

object of veneration for many centuries, and at one point

belonged to the Vatican, Calcata’s long history of marketing

it to pilgrims excited embarrassment and other ill feelings

(penis envy?) among the princes of the church, and changes in

Catholic theology made veneration of divine genitals more

problematic than it had previously been. In 1900, therefore,

the Vatican decreed that the parish could display its prize

holding only on New Year’s Day. It declared, furthermore, that

from that day forth anyone who spoke about the divine foreskin

would be subject to excommunication. Given the fact that Joyce

is up to speed on other aspects of the divine prepuce, it

seems likely that he would have known about this papal ban. If

so, he is making a point of spectacularly defying it, once in

Telemachus, again in Scylla and Charybdis,

and most volubly in Ithaca.