Forestalling any performance of Stephen's Shakespeare theory

until later, Mulligan declares in Telemachus, "I'm

not equal to Thomas Aquinas and

the fiftyfive reasons he has made to prop it up. Wait till I

have a few pints in me first." Stephen thinks of the

philosopher in Proteus: "Morose delectation Aquinas

tunbelly calls this." When he finally expounds his theory in Scylla

and Charybdis, he does not use Aquinian ideas nearly as

much as he did in articulating his aesthetic theorizings in A

Portrait; but he does refer affectionately to Aquinas

as a philosopher “whose gorbellied works I enjoy reading in

the original.”

The “original” of the huge ("gorbellied") Summa

Theologica and Summa contra Gentiles is

Latin, the language of the medieval Catholic church. Thomas

Aquinas (1225-1274) was a Dominican friar and theologian; the

Dominicans were as famous for intellectual rigor as the

Franciscans were for emotional fervor. The intricately logical

Scholastic method of Aquinas’ two big Summae sought

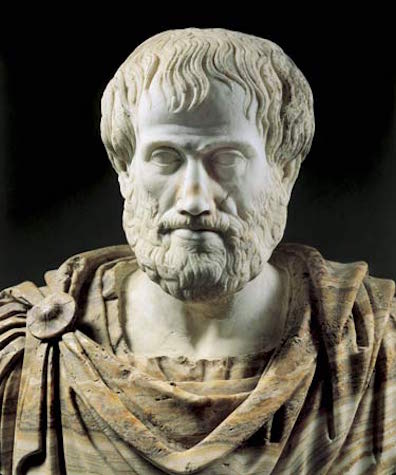

to reconcile Aristotelian

philosophy with Christian faith. Extremely controversial

in his own time, largely because of this synthesis of theistic

belief with pagan philosophy, by the end of the 19th century

Thomas had become absolutely canonical, recognized as the

greatest and most orthodox of all Catholic philosophers.

Stephen’s devotion to him has survived the lapse of his faith. In Scylla

and Charybdis, Buck Mulligan announces (with “malice”)

that “I called upon the bard Kinch at his summer residence in

upper Mecklenburgh street [a street in the red-light district]

and found him deep in study of the Summa contra

Gentiles in the company of two gonorrheal

ladies, Fresh Nelly and Rosalie, the coalquay whore.”

It is not only Aquinas' works that are gorbellied. According

to popular tradition the philosopher himself was immensely

fat, and anecdotes perpetuate the tradition: of holes cut in

tables to make room for his belly, of monks unable to carry

his dead body down the stairs from his sickroom, and so forth.

In Proteus Stephen thinks of him as "Aquinas

tunbelly." "Morose delectation" is

a translation of Delectatio morosa, which Thornton

identifies as one of three internal sins, consisting

(according to the Catholic Encyclopedia) of "the

pleasure taken in a sinful thought of imagination even without

desiring it." He directs readers to three passages in the Summa

Theologica.

“Fiftyfive reasons” certainly does suggest Aquinas’ method of

breaking large topics down into sub-topics, sub-sub-topics,

and sub-sub-sub-topics, then (at the level of the specific

question) proposing a statement of his belief, then

anticipating the most powerful objection that might be

advanced against that belief, then answering it with an “On

the contrary,” and finally detailing numerous precise reasons

for preferring his position. But it is also possible, Gifford

notes, that the number 55 may have been suggested by a detail

in Aristotle’s Metaphysics: the claim that beyond

the mutable region of the earth and moon lie “fifty-five

immutable celestial spheres,” perfectly “circular and

changeless.” If so, Joyce is rather naturally associating

Aquinas with the cosmological ideas of his master, Aristotle—a

philosopher whom Joyce also read with great devotion, and whom

Stephen invokes repeatedly in Nestor,

Proteus, and Scylla

and Charybdis.

Both of these philosophers, like Joyce himself, possessed

highly logical intellects and liked to categorize information.

Joyce once told a friend, “I have a grocer’s assistant’s

mind.” Early in the first chapter of A Portrait, he

has six-year-old Stephen write inside his geography book a

note that charts the categorical levels connecting him to the

highest reaches of the divinely ordered universe:

Stephen Dedalus

Class of Elements

Clongowes Wood College

Sallins

County Kildare

Ireland

Europe

The World

The Universe