In Telemachus Stephen thinks of the "mass for pope

Marcellus," pondering both the paradoxical achievement of the

music ("the voices blended, singing alone loud in

affirmation") and its religious significance ("and behind

their chant the vigilant angel of the church militant disarmed

and menaced her heresiarchs"). Musical tension between

multiplicity and unity, addressing a theological dispute about

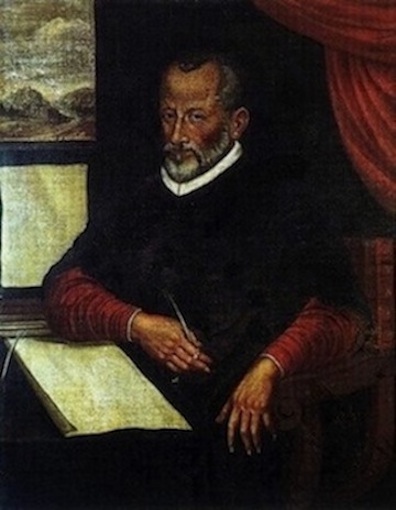

heresy and orthodoxy, was an essential concern of Giovanni

Pierluigi da Palestrina when he composed this great work of

Renaissance polyphony in or around 1564. The music clearly

meant a lot to Joyce: in Lotus Eaters he has Bloom too

mention Palestrina after thinking, "Some of that old sacred

music is splendid" and "Those old popes were keen on music."

It seems likely that Stephen may be considering the work's

relevance to composing a masterpiece in his own realm of

literary art.

Palestrina's mass is one of the highest achievements of

Renaissance sacred music, as spiritually powerful as it is

musically exquisite. It also reflects an ideological struggle.

When Stephen imagines that, behind the voices of the singers,

the Archangel Michael

("the vigilant angel") stands menacing all

those who would endanger Christian verities—Gifford observes

that Michael was often invoked in Catholicism’s struggle

against Protestantism in the 16th century—he is recalling a

church debate about what is acceptable in religious music.

Medieval church music had begun with monophonic "chant";

only over the course of centuries did polyphony (vocal music

with multiple melodic lines intersecting to produce chords)

become popular. In its counter-Reformation efforts to

strengthen the church, the Council of Trent (1545-63) issued

decrees against "music in which anything lascivious or impure

was mixed," and its sterner members argued that only chant

should be allowed in churches.

Palestrina was a brilliant composer of polyphony, and his

music was utterly dependent on church patronage. When

Marcellus II died in 1555, his successor Paul IV immediately

dismissed Palestrina from papal employment. But Paul's death

in 1559 opened the holy see to Pius IV, who was more

sympathetic to polyphony. In 1564 Pius commissioned Palestrina

to compose a polyphonic mass that would answer all the

objections to such music. Judging by the esteem in which

Palestrina has been held by Italians ever since, he succeeded.

Giuseppe Verdi said of the composer, "He is the real king of

sacred music, and the Eternal Father of Italian music." In James

Joyce and the Making of Ulysses (1934), Joyce's friend

Frank Budgen records that "He was a great admirer of

Palestrina, and that not alone for Palestrina's musical

achievements. It was as something of a hero that he regarded

the great Italian. / 'In writing the Mass for Pope

Marcellus,' said Joyce, 'Palestrina did more than

surpass himself as a musician. With that great effort,

consciously made, he saved music for the Church" (182).

It is not primarily theological doctrine, then, that Michael

is defending against heresiarchs when choirs sing this mass,

but sacred music itself. The righteous archangel evokes

Palestrina’s having successfully defended polyphony as aesthetically

orthodox. The singers' voices are polyphonically diverse ("blended"

together), but they sing "alone loud in affirmation”"in

a kind of "chant," just as multiple voices join to make

a single haunting voice in Gregorian plainsong. Thus the Mass

for Pope Marcellus is artistically innovative but still

traditional, an intricately complex mixture of diverse

elements yet still radiantly "pure" enough to satisfy the

censors.

By the time he wrote Ulysses Joyce had begun to use

his discarded Catholic religion as "a

system of metaphors" (Richard Ellmann's phrase) for his

literary art. It is quite plausible to imagine that he heard

in Palestrina's mass something similar to what he was

attempting to do in his great novel: carry sanctified literary

traditions like Homeric epic and Shakespearean drama forward

into the confusing welter of contemporary existence, and

combine a kaleidoscopic multitude of subject matters and

styles in a single aesthetically harmonious whole. As Stephen

stands on the Sandycove rocks, swept up in the inspiring power

of Palestrina's music, he may well be thinking about how "his

own rare thoughts" may produce a work of comparable power.

Gifford and Seidman note that Edward Martyn helped to

generate enthusiasm for Palestrina and his Renaissance

contemporaries in 1890s Dublin, and the mass for pope

Marcellus was first performed at St. Teresa’s church in 1898.

It is likely that Joyce attended this performance: he loved

the lute songs of the English Renaissance, and in Penelope

Molly thinks of having sung in a concert in "St Teresas

hall Clarendon St."