The many appearances of McCann in Stephen Hero are

pared to a single scene in A Portrait. There he is a

political activist—he is called a "propagandist" at one

point—who with "flushed bluntfeatured face" is rounding up

signatures on a "testimonial." Cranly says it is for universal

peace and Moynihan says it's for a "Brandnew world. No

stimulants and votes for the bitches." In an effort to get

Stephen to sign, MacCann "began to speak with fluent energy of

the Csar's receipt, of Stead, of general disarmament,

arbitration in cases of international disputes, of the signs

of the times, of the new humanity and the new gospel of life

which would make it the business of the community to secure as

cheaply as possible the greatest possible happiness of the

greatest possible number." Stephen declines, prompting MacCann

to call him a "reactionary." As Stephen politely differs and

walks away, MacCann says that he has "yet to learn the dignity

of altruism and the responsibility of the human individual."

This portrait seems faithful to the political affiliations of

Skeffington, whose causes included pacifism, socialism,

feminism, vegetarianism, and opposition to "stimulants" like alcohol and tobacco. But by representing

only one sharp-edged intellectual exchange it obscures other

qualities which strongly attracted Joyce to Skeffington. The

two men were friends, as Stephen Hero makes clear,

and Fargnoli and Gillespie note that "With the exception of

himself, Joyce considered Skeffington the cleverest man at

University College, Dublin." After his marriage in 1903

"Skeffy" worked as a journalist, supported by his wife's

teaching job, and compiled a substantial record in publishing.

He edited or co-edited the Nationalist (with Tom

Kettle), the Irish Citizen, and the National

Democrat (with Fred Ryan)

and wrote pieces for various newspapers and magazines. His

book-length biography of Michael Davitt was published in 1908,

and his novel In Dark and Evil Days was published

after his death in 1916.

Skeffington supported Home Rule and sympathized with some of

the militants agitating for Irish independence, but he

categorically renounced violence. When the Rising began in

April 1916 he avoided the fighting but organized volunteers to

stop poorer citizens from looting shops. Arrested on the

streets by British soldiers, he was taken to the Portobello

Barracks and executed by firing squad the next day. His murder

was probably not due so much to government or army policy as

to the blood lust of one minor officer. Captain John

Bowen-Colthurst, a decorated Cork-born officer in the Royal

Irish Rifles who had seen action in South Africa, Tibet, and

France, seems to have snapped during the street fighting in

Dublin. In addition to his order to kill Skeffington and two

other journalists, Colthurst himself shot other Dublin

residents in the streets without any justification. He was

arrested on May 6, court-martialed on June 6, found guilty but

insane, and sentenced to the Broadmoor Lunatic Asylum for one

year.

The story was a bitterly sad one for Colthurst, for the

commanding officer who reported him, and not least for Sheehy

Skeffington and his wife and young son. Ellmann records that

Joyce "followed the events with pity; although he evaluated

the rising as useless, he felt also out of things. His

attitude towards Ireland became even more complex, so that he

told friends, when the British had to give up their plans to

conscript troops in Ireland, 'Erin go bragh!' and

predicted that some day he and Giorgio would go back to wear

the shamrock in an independent Ireland" (399). The sadness

continued when Tom Kettle, Skeffington's journalistic

collaborator and brother-in-law, was killed while fighting in

France. Kettle was one of those Irishmen who volunteered to

serve in the army in the hope that Britain would later

reciprocate by giving Ireland home rule. The impulse was

generous but naive: it would have been wiser for politicians

to try bartering service in exchange for independence.

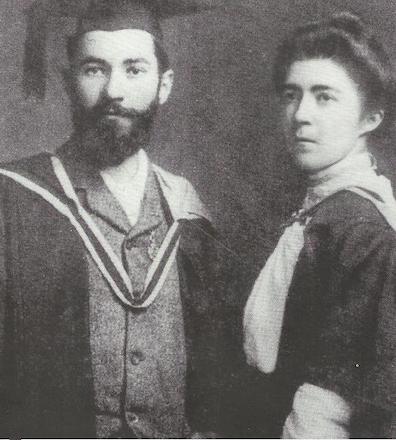

Elllmann records that when Joyce returned to Dublin in 1909

he "ran into Francis and Hanna Sheehy Skeffington. Skeffington

wanted to be friends, and seemed to have forgotten, as Joyce

had not, his refusal to be friendly in October 1904. He

pronounced Joyce 'somewhat blasé,' but Hanna said he was not a

bit changed. Joyce treated them coolly, as befitted an old

debtor with an old creditor, and subsequently refused an

invitation to dine" (278).