It is a tricky business, using quotations from works you have

not read to justify generalizations about life—especially when

the works in question are dramatic masterpieces in which

dozens of characters speak but the author does not. That does

not stop Mr. Deasy from enlisting the Greatest English Writer

in his cause of correcting Irish Catholic Ignorance. But if

the old blowhard is wrong to find moral authority in Iago, he

is right that Shakespeare was a capitalist entrepreneur.

First recalling an old proverb, Deasy then invokes no less a

figure than the Bard to justify his love of money: "If

youth but knew. But what does Shakespeare say? Put

but money in thy purse." Thornton cites the

old proverb, "If youth but knew what age would crave, it

would both get and save." The italicized phrase comes

from act 1 scene 3 of Othello, where Iago repeatedly

urges Roderigo to sell his lands, claiming that with the

money's help he can persuade Desdemona to love Roderigo. This

is hardly an instance of thriftily saving up for old age, and

in any case Iago is a sociopathic liar who is cheating

Roderigo of his wealth. (He confides to the audience that the

money will end up in his purse: "Thus do I ever make

my fool my purse.")

Ancient Greeks often approached the Homeric epics as if they

were owners' manuals for human life, and many modern

Christians oddly persist in viewing the Bible this way. In

Joyce's time there was a widespread cultural conviction that

life wisdom could be found in Shakespeare, and he implanted

that mindset in both Deasy and Bloom. Ithaca

notes that Bloom has often "reflected on the pleasures derived

from literature of instruction rather than of amusement as

he himself had applied to the works of William Shakespeare

more than once for the solution of difficult problems in

imaginary or real life." "Had he found their

solution?" the catechism asks. "In spite of careful and

repeated reading of certain classical passages, aided by a

glossary, he had derived imperfect conviction from the text,

the answers not bearing in all points."

The narrative's mockery of Bloom here echoes Stephen's

earlier contempt for Deasy, which he expresses so

politely that Deasy does not notice the rebuttal:

— Iago, Stephen

murmured.

He lifted his gaze from the

idle shells to the old man's stare.

— He knew what money

was, Mr Deasy said. He made money. A poet, yes, but an

Englishman too.

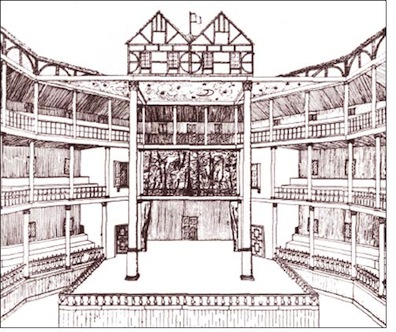

Shakespeare did make money, and not accidentally. He was one

of a handful of "sharers" (i.e., shareholders) in the Lord

Chamberlain's (later the King's) Men, in the Theatre (later

the Globe), and in the plays that the acting company produced

in those theaters. The partners split obligations and profits

according to their stake in the whole. Shakespeare's share was

originally one eighth, 12.5%, but at the time of his

retirement he held about 7%. His shares must have produced a

sizeable income, because as he aged he purchased a lot of real

estate in and around his home town, Stratford. He did exactly

what the proverb recommends, saving up for a time when money

would be important, and in much the same way as Bloom has done

by purchasing Canadian railway stock paying a 4% dividend.

Stephen's utter lack of

thrift means that he could learn something from both

Deasy and Bloom, but the odds that he will do so anytime soon

are vanishingly small. Accepting Deasy's point about

Shakespeare's love of money, he makes this "English" quality

an object of derision rather than admiration in Scylla

and Charybdis: "He drew Shylock out of his own long

pocket. The son of a maltjobber and moneylender he was himself

a cornjobber and moneylender, with ten tods of corn hoarded in

the famine riots. His borrowers are no doubt those divers of

worship mentioned by Chettle Falstaff who reported his

uprightness of dealing. He sued a fellowplayer for the price

of a few bags of malt and exacted his pound of flesh in

interest for every money lent."