Deasy responds to Stephen's bleak view of history with

quintessential Victorian optimism: "All human history moves

toward one great goal, the manifestation of God." Taking his

assertion more or less seriously, Stephen answers that if God

is in the business of manifesting himself in human history

then even the basest things must be divine.

Thornton identifies two close analogues to Deasy's statement:

Alfred, Lord Tennyson's hopeful vision of "one far-off divine

event, / To which the whole creation moves," at the end of In

Memoriam (1850), and Matthew Arnold's lines from Westminster

Abbey (1881), "For this and that way swings / The flux

of mortal things, / Though moving inly to one far-set goal."

Gifford observes that by the end of the 19th century such

"faith in the inevitability of man's moral and spiritual

progress...was widely regarded as a feeble substitute for

vital spiritual commitment."

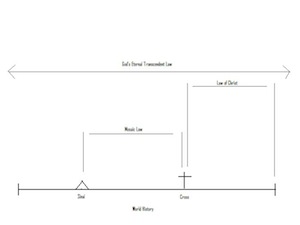

The idea that history has a telos or purposeful

end-point had long been associated in western culture with the

historiography of the Christian church, whose ideas of

apocalypse, judgment, and revelation Joyce contrives to

associate, derisively, with the "goal" being

scored on the hockey field. The Christian conception of

history is marked by a beginning (the Creation), a middle (the

Incarnation), and an end (the Last Judgment). Although God

exists outside of time, he reveals his providential plan in

such linear developments, and so history can be seen as the

ongoing record of his self-manifestation, with the fullest

revelation coming at the end of time. Some secular western

historiographies, such as Hegel's description of human history

as a progressively greater manifestation of Geist or

Spirit, have drawn on this Christian model, and in 19th

century Britain the swelling tide of industry, science,

empire, and commerce encouraged a new belief in "progress."

Against such schemes depicting history as a linear

progression, Joyce seems to have preferred circular or

cyclical models which describe human experience perpetually

revisiting similar states of being, with no clear beginning or

end. The early lecture "Drama and Life" (1900) describes

eternal human truths that express themselves perpetually and

unchangingly in human experience. The Viconian historiography

of Finnegans Wake augments this eternal sameness

with the idea of recurring cycles.

In Proteus, Stephen continues thinking about ideas

of history. He harshly dismisses the triumphant

transcendentalism of Deasy's "one great goal" when he watches

a live dog sniffing a dead one on the tidal flats: "Dogskull,

dogsniff, eyes on the ground, moves to one great goal.

Ah, poor dogsbody! Here lies poor dogsbody's body."

Here, the great goal of life is clearly death. When Stephen

contemplates the decomposing body of the drowned man at the

end of Proteus, it becomes apparent that his focus

on the death of the organic body does not represent simply a

cynical or nihilistic rejection

of metaphysical explanations; but it does constitute a

rejection of Christian metaphysics.