Having followed the

"strandentwining cable of all flesh" back to Eden, Stephen

spends one paragraph in Proteus thinking about the

First Woman. An assortment of literary texts informs his

meditation on "naked Eve." Here and again later in the

chapter, he thinks also of Adam before the Fall. He returns to

his thoughts about Eve in Oxen of the Sun, and in Wandering

Rocks he again recalls a passage from Thomas Traherne's

Centuries of Meditations that inspires his thinking

about Edenic perfection.

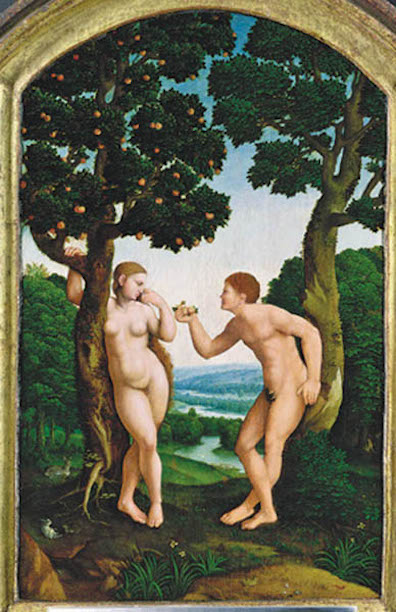

He might have found in many different texts the notion that "She

had no navel." It is not in Genesis, but

many theologians have argued that, since neither Adam nor Eve

was born in the usual way, they would not have possessed belly

buttons. When Michelangelo put a belly button on his Adam in

the Sistine Chapel, some theologians accused him of heresy.

Thomas Browne devoted an entire chapter of the Pseudodoxia

Epidemica to the "vulgar error" of painters who depict

the First Couple with navels. Most painters through the ages,

however, have rejected the smooth-belly hypothesis. The canvas

shown here is a relative rarity. Stephen prefers to think of

such a "Belly without blemish," and in Oxen

he thinks again of Eve's body undistorted by the familiar

processes of gestation and birth: "A pregnancy without

joy, he said, a birth without pangs, a body without

blemish, a belly without bigness."

Thornton hears in "whiteheaped corn" an echo

of the Song of Solomon: "Thy navel is like a round

goblet, which wanteth not liquor: thy belly is like an heap of

wheat set about with lilies" (7:2). Stephen, however, changes

"wheat" to "corn" (a word which meant simply "grain" before

the modern era): "no, whiteheaped corn, orient and

immortal, standing from everlasting to everlasting."

This word allows him to pivot to a passage from Thomas

Traherne's 17th century prose Meditations. Section 3

of the third Century rapturously recalls a vision of Edenic

perfection that the author had when he was a child: "The Corn

was Orient and Immortal Wheat, which never should be reaped,

nor was ever sown. I thought it had stood from everlasting to

everlasting." In this lovely passage, Stephen gets as close as

he will to the mystical gazing on perfection that is

apparently driving his meditation ("That is why mystic

monks. Will you be as gods? Gaze in your omphalos. . . .

Gaze). But, as William York Tindall pointed out in

A Reader's Guide to James Joyce (1959), Stephen could

not actually have made such an allusion in 1904, because the Centuries

were not published in a modern edition until 1908 (148).

"Heva" approximates early Hebrew versions of

Eve's name: Cheva/Chawwah, derived from chawah

("to breathe") or chayah ("to live"). Eve is

described as "Spouse and helpmate" of Adam in

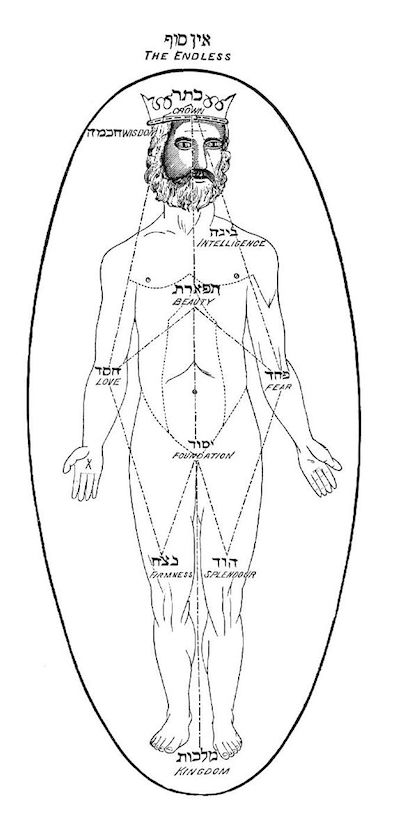

Genesis. "Adam Kadmon" is a phrase

from the Kabbalah meaning "original man." Thornton notes that

"He includes all of the ten Sephiroth or intelligences which

emanated from the En Soph." Gifford speculates that Joyce may

have taken the phrase from its theosophical elaboration in

texts like Helena Blavatsky's Isis Unveiled (1886),

but there is nothing in Stephen's sentence to indicate any

particular theoretical intention.

Later in Proteus, Stephen recalls Edenic perfection

one last time when he thinks of "Unfallen Adam rode

and not rutted." As Gifford puts it, "According to

tradition, before the Fall sexual intercourse was without

lust."