In Proteus Stephen thinks, "Isle of Saints," and in

Cyclops the Citizen exclaims, "Island of saints and

sages!" They are voicing a common Irish expression that

recalls the early medieval times when Irish monks like Columbanus brought Christian

spirituality and learning to Europe after the collapse of the

Roman empire. The phrase also evokes the title of a lecture,

"Ireland, Island of Saints and Sages," that Joyce delivered in

1907 at the Università Popolare in Trieste, introducing to

Italians the notion that his island once housed a great

civilization.

In the talk, Joyce observed that Irish people cling to the

phrase because "Nations have their ego, just like

individuals." The spiritual character of Ireland was

established long before the arrival of Christianity: "The Druid priests had their temples

in the open, and worshipped the sun and moon in groves of oak

trees. In the crude state of knowledge of those times, the

Irish priests were considered very learned, and when Plutarch

mentions Ireland, he says that it was the dwelling place of

holy men. Festus Avienus in the fourth century was the first

to give Ireland the title of Insula Sacra; and

later, after having undergone the invasions of the Spanish and

Gaelic tribes, it was converted to Christianity by St. Patrick

and his followers, and again earned the title of 'Holy Isle'."

In the Christian era, the druids' highly learned priesthood

gave way to monastic scholarship that kept the intellectual

traditions of the West alive through the Dark Ages: "It seems

undeniable that Ireland at that time was an immense seminary,

where scholars gathered from the different countries of

Europe, so great was its renown for mastery of spiritual

matters." Joyce stresses that he is not speaking of

Christianity for its own sake, but because in those days it

sheltered and fostered learning, art, and spirituality: "in

the centuries in which they occurred and in all the succeeding

Middle Ages, not only history itself, but the sciences and the

various arts were all completely religious in character, under

the guardianship of a more than maternal church."

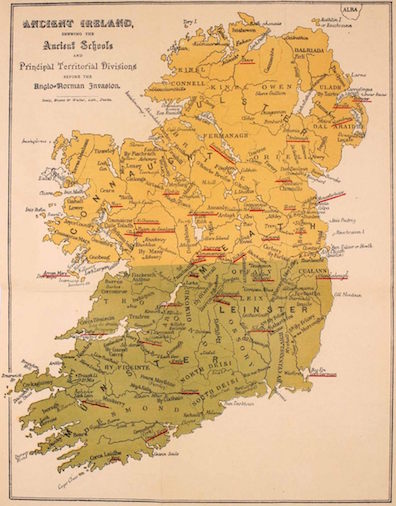

The relentless Viking

invasions of the 9th and 10th centuries weakened this

civilization, and the Anglo-Norman invasions of the 12th

century sealed its fate: "Ireland ceased to be an intellectual

force in Europe. The decorative arts, at which the ancient

Irish excelled, were abandoned, and the sacred and profane

culture fell into disuse." Eight centuries of colonial

capitulation and degradation followed, with the result that

"the present race in Ireland is backward and inferior."

"Ancient Ireland is dead just as ancient Egypt is dead."

But the Irish genius has remained alive throughout that time,

Irish industry and ingenuity have flourished in foreign

countries, and Irish valor has won Britain's wars. "Is this

country destined to resume its ancient position as the Hellas of the north some

day? Is the Celtic mind, like the Slavic mind which it

resembles in many ways, destined to enrich the civil

conscience with new discoveries and new insights in the

future? Or must the Celtic world, the five Celtic nations,

driven by stronger nations to the edge of the continent, to

the outermost islands of Europe, finally be cast into the

ocean after a struggle of centuries?"

Joyce acknowledges that he cannot answer these questions.

But "even a superficial consideration will show us that the

Irish nation's insistence on developing its own culture by

itself is not so much the demand of a young nation that wants

to make good in the European concert as the demand of a very

old nation to renew under new forms the glories of a past

civilization."