As he walks on Sandymount Strand Stephen imagines having been

alive in the 1330s

as a different "I, a changeling."

Changelings, commonly encountered in Irish folklore (as in W.

B. Yeats' poem The Stolen Child), are mysterious

beings swapped for human children by the fairies—or,

sometimes, the stolen children themselves. The belief probably

arose as an explanation for birth defects, diseases, and other

afflictions. It is not clear why Stephen thinks of past lives

in these terms, or even that he believes he had one. He may

only be imagining himself as a fairy child raised in a

medieval bed as a fanciful way of indulging a historical

revery. But a sense of deep racial identity informs his

imagined ability to travel through time: "Their blood

is in me, their lusts my waves."

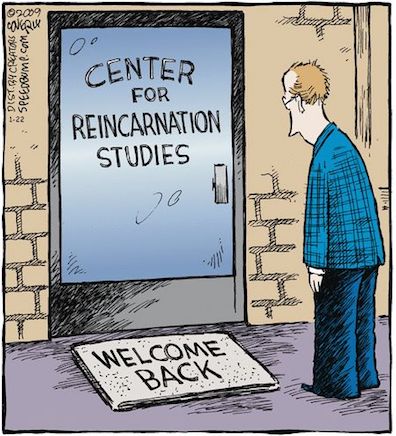

Less than a page later, Stephen explicitly thinks of

reincarnation, whimsically imagining that the dog he sees

nosing about the beach is "Looking for something lost

in a past life." Still later in Proteus,

he broadens the concept of transmigration from temporal to

spatial extension. Somewhere out there in the innumerable "worlds"

that Giordano Bruno

supposed to populate the cosmos there is a parallel universe,

some unknown planet in which Stephen plays a part: "Me

sits there with his augur's rod of ash, in borrowed

sandals, by day beside a livid sea, unbeheld, in violet night

walking beneath a reign of uncouth stars." Opposing the

Christian cosmology of his time, Bruno proposed that the

universe had no center and that the innumerable stars visible

in the heavens were suns that might have their own

life-bearing planets. He also affirmed the transmigration of

the soul.

Bruno was going back to Plato, and beyond him Pythagoras.

When Molly asks her husband the meaning of "met him pike

hoses," which she has encountered in

a novel, he evinces some awareness of this ancient

history: "— Metempsychosis, he said, frowning.

It's Greek: from the Greek. That means the transmigration of

souls." The word is indeed Greek, and the belief

was one feature of Orphic religion in ancient Thrace: Orpheus

was said to have taught that a life of ascetic purity could

liberate the soul from an otherwise endless cycle of

reincarnation. The 6th century BCE philosopher Pythagoras

apparently brought the doctrine into greater Greek

circulation, practicing vegetarianism in the belief that

abstaining from harming other sentient beings could affect the

soul's reincarnation in one animal form or another. This

Pythagorean aspect of the doctrine appears in Lestrygonians

when Bloom thinks of vegetarians: "Only weggebobbles and

fruit. Don’t eat a beefsteak. If you do the eyes of that

cow will pursue you through all eternity."

Many of Plato's works in the early 4th century BCE suggest

that he was strongly influenced by the Pythagorean doctrine.

The myth at the end of the Republic recounts how a

man named Er came back from the dead to tell how departed

human souls are judged and then choose new forms of existence,

many of them animal. Er also saw animals taking the forms of

other animals, as happens repeatedly in Proteus and Circe.

The Phaedrus and the Meno suggest that true

knowledge involves anamnesis or recollection of things

we have encountered in the realm of Ideas between our

different incarnations, and the Phaedo, the Timaeus,

and the Laws all contain thoughts about the doctrine.

Some later classical writers referred disparagingly to

reincarnation, but Virgil made it a central component of his

eschatology in book 6 of the Aeneid, and it was

explored sympathetically by Plotinus and the Neoplatonists.

Bloom's definition of metempsychosis as "the transmigration

of souls" leaves Molly thoroughly unimpressed: "— O,

rocks! she said. Tell us in plain words." In response,

he silently racks his brain for what he knows: "That we

live after death. Our souls. That a man's soul after he

dies. Dignam's soul..." Impressively, he rouses his

inner lecturer to give his wife a brief but coherent account:

"— Some people believe, he said, that we go on

living in another body after death, that we lived before.

They call it reincarnation. That we all lived before on the

earth thousands of years ago or some other planet. They say

we have forgotten it. Some say they remember their past

lives." Interestingly, Bloom too makes the

connection to living on "some other planet."

Realizing that even this may not mean much to Molly, he tries

again, with unfortunate results: "— Metempsychosis, he

said, is what the ancient Greeks called it. They used

to believe you could be changed into an animal or a tree,

for instance. What they called nymphs, for example."

Metempsychosis should not be conflated with metamorphosis as

Bloom does, but there is certainly overlap, as reincarnation

erases the boundary between animal and human. Ulysses

plays both with metamorphosis in this life (as when human

beings are changed into countless animal forms in Circe)

and with metempsychosis in the afterlife. The two conceptions

share the notion that, in Bloom's words, "we go on living in

another body."

In Nausicaa Bloom watches a bat flitting about near

Paddy Dignam's old house and thinks, "Metempsychosis. They

believed you could be changed into a tree from grief.

Weeping willow. Ba. There he goes. Funny little beggar.

Wonder where he lives. Belfry up there. Very likely. Hanging

by his heels in the odour of sanctity." Paddy returns in

Circe as a baying beagle to announce, Hamlet-like,

"Bloom, I am Paddy Dignam's spirit. List, list, O list!" When

one policeman, piously crossing

himself, asks, "How is that possible?" and the other one

says, "It is not in the penny catechism," Dignam

answers, "By metempsychosis. Spooks." In these two

passages, Joyce uses the recently departed Dignam to suggest

that the Catholic church's Last Things (Hell, Paradise, and

the Purgatory that Hamlet Sr. reports on) may not be the only

realities that human beings can encounter after death.

The ancient Greeks and Romans almost certainly derived their

ideas of reincarnation ultimately from Indian doctrines that

reach back to the Upanishads. No doubt Joyce encountered some

of these more directly in theosophical

writings of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One

section of Cyclops hilariously employs words covered

with Sanskrit-like diacritical marks to narrate Dignam's

afterlife experiences. Such passages may easily be dismissed

as comic hyperbole, but they plant the seeds of speculation.

Whatever Ulysses may be judged to say or not say

about the afterlife, these quasi-eastern thoughts about

reincarnation clearly do invite the reader to think about the

mutability of human personality and the permeability of its

boundaries. In Hades, as Dignam's coffin is diving

down into the dark and the men handling the ropes are

struggling "up and out" of the grave, Bloom thinks, "If

we were all suddenly somebody else." To pursue that

thought, speculations about the destination of Dignam's soul

are unnecessary. Much of Circe can be read as people

suddenly becoming somebody else in the here and now, and Scylla

and Charybdis explores the mechanisms by which

Shakespeare did so again and again in his plays.

Viewed in this way, metempsychosis is another name for

self-knowledge: the ability to imagine the different forms

that one's life can take. It is also a name for empathy or

compassion: the ability to feel the sufferings of others as if

one lived within their bodies. The word is used in this second

way in Oxen of the Sun, when Bloom contemplates "the

wonderfully unequal faculty of metempsychosis possessed by"

the medical students, who cannot imagine the effect that their

raucous laughter may be having on the unfortunate woman trying

to give birth. Remembering a past life "in another body"

probably has less ultimate value than being able to loosen the

bonds of self imposed by inhabiting a body in this life.