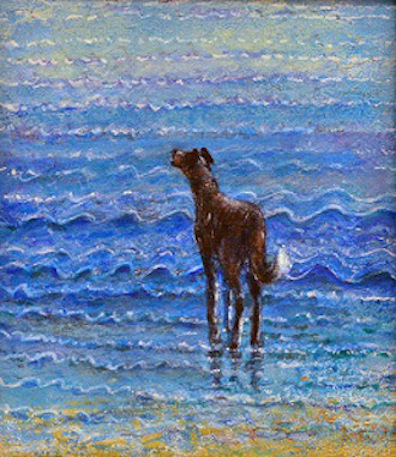

Authorial simile in Proteus briefly changes the dog

on the beach into a different animal: "Suddenly he made off

like a bounding hare, ears flung back, chasing the shadow of a

lowskimming gull." Further protean animal metamorphoses ensue,

anticipating the kaleidoscopic transformations of the dog in Circe.

The comparisons must be instances of free indirect narration

approximating the contents of Stephen's consciousness, because

soon after the first of them his interior monologue turns the

dog into a deer, using the language of heraldry: "On a field

tenney a buck, trippant, proper, unattired." At the end of the

chapter, Stephen himself is presented in the language of

heraldry.

In a personal communication, Ole Bønnerup offers the

wonderful observation that Stephen's "buck, trippant"

echoes Mulligan's characterization of himself in Telemachus:

"Tripping and sunny like the buck himself." But Stephen

manages to map this remembered phrase onto technical

terminology. In the language of heraldry, "passant" refers to

an animal walking past the viewer, looking straight ahead. (If

he looks at the viewer, the word "gardant" is added.) Unlike

other animals, a deer depicted in this posture is called "trippant."

Stephen presumably sees the dog moving across his field of

vision in this way. He also sees it "On a field tenney"

(tenné = orange or tawny, i.e. the beach), "proper"

(in his natural colors, i.e. not changed by demands of

iconography), and "unattired" (without

antlers, i.e., a dog).

All of this happens in the midst of the narrative's slightly

more realistic depiction of the animal. When the hare-dog

hears its master calling, it comes back, now sounding vaguely

like a horse or deer, and stops at the water's edge to watch

more life-forms approaching: "He turned, bounded back, came

nearer, trotted on twinkling shanks. On a field tenny a buck,

trippant, proper, unattired. At the lacefringe of the tide he

halted with stiff forehoofs, seawardpointed ears. His snout

lifted barked at the wavenoise, herds of seamorse. They

serpented towards his feet, curling, unfurling many crests,

every ninth, breaking." "Seamorse," which the OED

identifies as an archaic name for a walrus, captures the

heaviness of the breaking waves. "Serpented" captures their

sinuous many-headed advance. "Every ninth" foregrounds the

human habit of looking for patterns in the fluctuations of

magnitude in incoming waves.

In the following paragraph, the dog becomes a bear: "The dog

yelped running to them, reared up and pawed them, dropping on

all fours, again reared up at them with mute bearish fawning."

And a wolf: "Unheeded he kept by them as they came

towards the drier sand, a rag of wolf's tongue redpanting

from his jaws." And a cow: "His speckled body ambled

ahead of them and then loped off at a calf's

gallop." In the paragraph after that, he plays the part of the

fox in Stephen's riddle: "His hindpaws then scattered the

sand: then his forepaws dabbled and delved. Something he

buried there, his grandmother." And finally he leaves in a

flurry of changing forms: "He rooted in the

sand, dabbling, delving and stopped to listen to the air,

scraped up the sand again with a fury of his claws, soon

ceasing, a pard, a panther, got in spousebreach, vulturing

the dead."

Thornton traces the leopard and panther to several works in

the medieval tradition of fantastic bestiaries. The most

relevant seems to be the encyclopedic compendium called De

Proprietatibus rerum (On the Properties of Things),

written in the 13th century by a Franciscan friar named

Bartholomeus Anglicus (Bartholomew the Englishman) and

translated into English in the late 14th century by a Cornish

writer named John de Trevisa. The OED quotes this

sentence from the work: "Leopardus is a cruel beeste and is

gendered in spowsebreche [i.e., adultery] of a parde and of a

lionas." On the other hand, the "fury of his claws"

may justify William Schutte's suggestion that Joyce is

following Brunetto Latini's Il Tesoro, which

explains why the female panther gives birth only once: her

young will not wait for the proper time and tear their way out

of her womb.

In the final paragraph of Proteus Stephen himself is

described in heraldic terms as he looks back over its

shoulder: "He turned his face over a shoulder, rere

regardant." In James Joyce and Heraldry

(SUNY Press, 1986), Michael J. O'Shea notes that "None of the

English sources to which I have referred uses the expression

'rere regardant' (they simply use 'regardant' to describe the

lion looking back over its shoulder) except Barron. But Barron

is citing old French usage" (181). The fact that "regardant"

was used to describe lions extends the web of connections to

still one more animal image: "The lions couchant on the

pillars" of Mr. Deasy's gateway at the end of Nestor. There,

Stephen turns back at the gate and sees the sun fling spangles

of light on the "wise shoulders" of his Nestor. At the end of

Proteus he looks back over his own shoulder to see the

masts of a ship evocative of the homecoming of Ulysses.