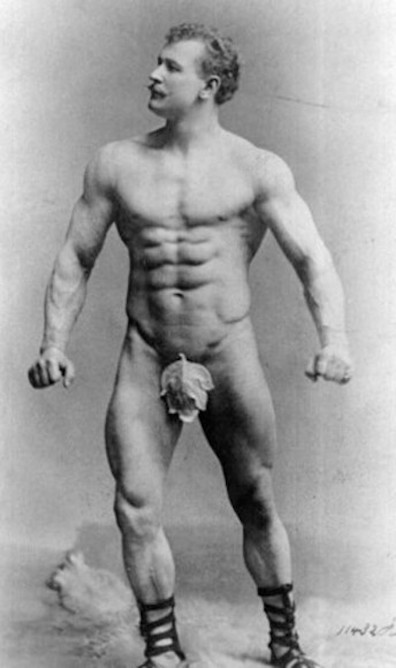

Friedrich Wilhelm Müller, born in Prussia in 1867, gave

himself the stage name Eugen Sandow when he began performing

in European circuses in the 1880s. In addition to performing

staggering feats of strength, he adopted poses that would

highlight particular aspects of his musculature, as

professional bodybuilders do today. In the 1890s Sandow opened

schools that taught exercise routines, healthy diets, and

weight training. He published a monthly magazine called Physical

Culture starting in 1898, wrote several books (which

included charts prescribing amounts of weight and numbers of

repetitions), invented new kinds of exercise equipment, and

championed isometric exercises (merely tightening and

releasing muscle groups) as a complement to weight-lifting.

In addition to performing internationally, Sandow organized

bodybuilding competitions, trained soldiers, and served for a

while as a personal trainer to King George V. In May 1898 he

delivered a run of spectacular performances in Dublin's Empire

Palace Theatre. More than 1,300 people came on the first night

to see him effortlessly lift enormous dumbbells, throw human

beings around like beanbags, rip three decks of playing cards

stacked on top of one another, and lift up a platform

containing a piano while the pianist continued playing on it.

Sandow enjoyed a sky-high reputation in Ireland for many years

after the 1898 tour, and sold many copies of his books as well

as the Sandow Developer, a pulley system for dumbbells that

anticipated modern weight-lifting machines. A good account of

the Irish Sandow craze can be found at www.theirishstory.com.

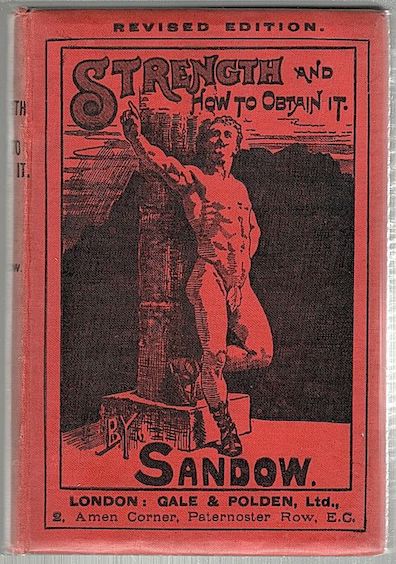

Sandow's most famous book, Strength and How to Obtain It

(1897)—Joyce got the title slightly wrong—supplied a chart for

recording measurements of particular muscle groups, so that

the practitioner could track their growing size. Ithaca

observes that these "indoor exercises . . . designed

particularly for commercial men engaged in sedentary

occupations, were to be made with mental concentration in

front of a mirror so as to bring into play the various

families of muscles and produce successively a pleasant

rigidity, a more pleasant relaxation and the most pleasant

repristination of juvenile agility." Later, when it details

the contents of Bloom's desk drawer, the chapter mentions "a

chart of the measurements of Leopold Bloom compiled before,

during and after 2 months' consecutive use of Sandow-Whiteley's

pulley exerciser (men's 15/-, athlete's 20/-) viz.

chest 28 in and 29 1/2 in, biceps 9 in and 10 in, forearm 8

1/2 in and 9 in, thigh 10 in and 12 in, calf 11 in and 12 in."

Alas, like many later 20th and 21st century individuals who

have purchased exercise advice and exercise equipment, Bloom

suffered a lapse of enthusiasm after his two months of

faithful adherence. Ithaca notes that his Sandow's

routines were "formerly intermittently practised, subsequently

abandoned." In Calypso, his brief plunge into black

gloom on Dorset Street

makes him resolve to improve his physical conditioning:

"Morning mouth bad images. Got up wrong side of the bed. Must

begin again those Sandow's exercises." In Circe,

a near encounter with a tram causes him to renew the

resolution: "Close shave that but cured the stitch. Must

take up Sandow's exercises again."

Sandow advocated what he called the "Grecian ideal" of male

beauty, shaping his own body to measurements of muscles that

he took from statues in museums. Bloom's interest in the

Sandow ideal is clearly of a piece with his admiration for the

standards of beauty embodied in Greek

statues, both male and female. His mimetic desire for

the one and sublimated sexual desire for the other merge with

any purer aesthetic appreciations he may have, making his

response to this great art form as much "kinetic" as "static,"

in the terms that Stephen propounds in Part 5 of A

Portrait of the Artist.

[2019] Bloom's conscious thoughts about Sandow are limited to

desiring physical strength, but his mimetic attraction to this

brilliant self-promoter may express professional envy as well.

As Vike Martina Plock observes in Joyce, Medicine, and

Modernity (UP of Florida, 2010), "Both physically and

commercially Sandow has achieved what Leopold Bloom can only

dream of: physical superiority and professional success in

advertising" (119). Sandow's books and magazine, his

theatrical triumphs, his classes, his exercise products, his

marketing of his services as a consultant, his modeling for

photographs: Bloom would count himself fortunate to achieve

any one of these commercial successes.

In a personal communication, fitness trainer and writer

Andrew Heffernan adds several other interesting pieces of

information. Sandow completely changed the look of

weight-lifters: "Prior to him, strongmen were thick-waisted

beer-guzzling bears." In order to accentuate the resemblance

to ancient statues, he would cover himself in white powder

that gave his body the appearance of having been carved from

marble. And Sandow "was—and remains—the model for the trophy

given annually to the winner of the Mr. Olympia

contest—bodybuilding's top prize." Heffernan's photograph of

one of these trophies appears here.