Molly's request for another Paul de Kock book makes Bloom

think, "Must get that Capel street library book renewed or

they'll write to Kearney, my guarantor." The public

library on Capel (pronounced KAY-pəl) Street, one of the first

two in the city's history, was approaching its twentieth

anniversary at the time represented in the novel. Bloom has

secured the backing of a nearby businessman to obtain

borrowing privileges, which were not extended to just anyone.

The library is mentioned also in Wandering Rocks

(Miss Dunne has borrowed a Wilkie Collins novel), Ithaca

(Bloom has borrowed an Arthur Conan Doyle book for himself),

and Eumaeus. The street itself surfaces in

characters' thoughts in Cyclops and Nausicaa.

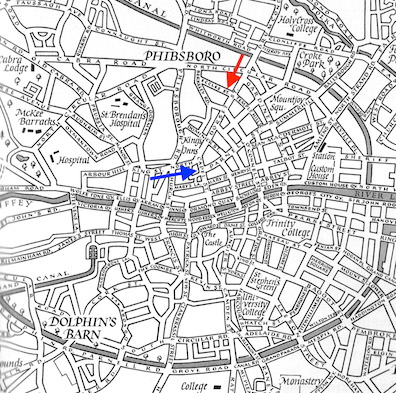

From a point in the very center of Dublin, the largely

commercial Capel Street runs northward from the River Liffey

for a little over a third of a mile, ending near the southern

terminus of Dorset Street.

It is easy to imagine Bloom walking half a mile down one of

his favorite shopping streets and turning into Capel to borrow

books. Gifford notes that a book and music seller named Joseph

Kearney had a Capel Street shop across the street from the

library, but his address for the library is mistaken (it was

at 106, not 166), so Kearney's shop would actually have been

several blocks away.

Many lending libraries in Ireland, and around the world,

still require young people to have an adult "guarantor"

in order to receive a borrowing card, but it would be unusual

today to require that of someone over 18 years of age. Bloom's

need to have a local businessman co-sign his borrower's

application reflects the pervasive poverty in 1904 Dublin,

where financial solvency could be expected of only a small

percentage of the population. In his foreword to Joseph

O'Brien's Dear, Dirty Dublin (1982), Hugh Kenner

observes that "by 1908 when shortage of funds closed the

entire system down only 6,000 books were on loan to about that

many cardholders" (ix). The libraries had to impose stringent

terms to keep their books from disappearing or being damaged.

The notice from the Lending Department reproduced alongside

this note specifies that "Application will be made to the

Borrower for the return or value of the Book, if the same be

not promptly returned; and in case of refusal

or neglect, proceedings will be taken to recover the same." If

a borrower does not agree to pay for damages caused to a book,

"application will be made to the Guarantor."

The Public Libraries Act of 1855 allowed for the

establishment of free public lending libraries in Dublin, but

the Corporation did not form a committee to do so until 1883.

Two run-down Georgian tenement houses in Capel Street and

Thomas Street were obtained for the purpose, to serve the

north and south sides of the city respectively, and they

opened within hours of each other on 1 October 1884.

The Dublin City Council website, from which two of the

photographs on this page are taken, notes what a momentous

development in the life of the city this was: "To mark the

occasion, the Library Association of the United Kingdom held

its Annual Conference in Dublin for the first and only time.

Conference delegates attended the opening ceremony. Patrick

Grogan, formerly a librarian at Maynooth College, became the

first librarian at Capel Street. The staff was composed of a

librarian, three library assistants, and a hall porter. The

Capel Street library proved popular with the inhabitants of

what was then a heavily industrialised area of the city. A

newsroom had to be constructed at the rear of the building to

accommodate 400 readers. A Ladies Reading Room was opened on

24 May 1895 and attracted a monthly attendance of 780. The

daily average of books issued in 1901 was almost 300 volumes.

In 1902 the daily average attendance in the newsroom was

1,200."

Bloom's ability to take books home for two weeks, rather than

having to look at them in a crowded reading room, marks him as

a relatively prosperous and privileged member of Dublin

society.