Bloom's speculation about Mr. Woods goes straight to his

domestic arrangement: "Wife is oldish. New blood. No

followers allowed." By his suspicious logic, the

servant girl is not at 8 Eccles just to perform domestic

chores, but to provide a remedy to the problem of an aging

wife. "No followers" was a common Dublin employment condition

to keep maids from bringing distracting and possibly felonious

boyfriends or suitors to their place of work. Bloom imagines

Woods laying down this condition to establish a monopoly of

sexual access to his attractive young helper.

He is clearly extrapolating from personal experience. Circe

dramatizes the erotic interest he took in a "scullerymaid"

named Mary Driscoll, which may have led to a physical advance

on his part, and which may have emboldened Mary to steal some

oysters from the Blooms. Molly thinks about the events in Penelope,

remembering Mary "padding out her false bottom to excite him"

and stealing potatoes and oysters, and suspecting that Bloom's

complicity gave her some encouragement to act so outrageously.

Bloom's propensity for voyeurism combines with his

identification with a fellow employer to make the girl next

door an object of erotic longing: "Strong pair of arms.

Whacking a carpet on the clothesline. She does whack it, by

George. The way her crooked skirt swings at each whack." Bloom

clearly has gazed into his neighbor's back yard when the

servant girl was working there. He may not have quite imagined

himself a carpet, but his appreciation of her aggressive vigor

implies some masochistic

interest in this young woman. Consistent with his marked

anality, he seems also to

have been particularly excited by the sight of her "vigorous

hips," which he is now staring at again.

Standing in a place where meat is sold, his admiration of the

woman's rump becomes translated into the language of

commodification and consumption: "Sound meat there: like a

stallfed heifer." Bloom remembers his days in the cattle

market, when the breeders would walk among the stock,

"slapping a palm on a ripemeated hindquarter, there's a prime

one, unpeeled switches in their hands." He hopes that his

business will be concluded quickly enough "To catch up and

walk behind her if she went slowly, behind her moving hams."

The "Brown scapulars in

tatters" that the poor girl wears, "defending her both ways,"

testify to her vulnerability working for low wages in a home

far from her own, unprotected by male relatives. As if in

recognition of this fact, Bloom's fantasy concludes with the

thought that she is not really for Mr. Woods or for himself,

but "For another: a constable off duty cuddled her in

Eccles lane. They like them sizeable. Prime sausage. O

please, Mr Policeman, I'm lost

in the wood." Either Bloom has actually seen the girl

flirting with such a policeman in Eccles Lane, which runs

behind Eccles Street to the hospital, or he has imagined it.

Such a hero can rescue a damsel lost in the Woods, he wittily

supposes. This figure returns in fantasy in Circe: "the

constable off Eccles Street corner."

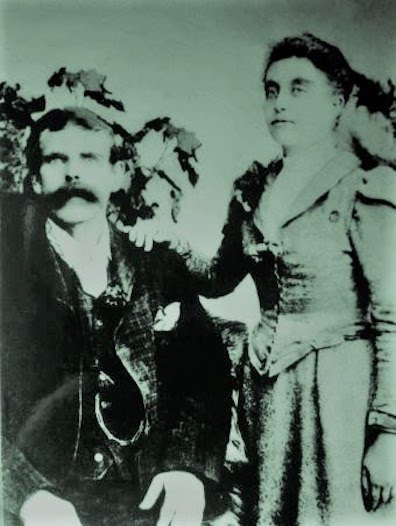

Gifford notes that the 1904 Thom's lists a Mr. R.

Woods as living at 8 Eccles Street, one door west of Bloom's

house, and that "He is listed again under 'Nobility, Gentry,

Merchants, and Traders' (p. 2043), but his vocation is not

identified." In giving a place in the narrative to someone who

actually lived in the neighborhood, Joyce continued the

verisimilitude maintained by placing the fictional Bloom in a

house that was unoccupied in

1904. But in fact Thom's was wrong about the

person living in the house next door in 1904. "R. Woods" was

Rosanna Woods, wife of Patrick, and although the couple had

lived together in the house at the time of the national census

in 1901, they separated in 1902 and after that Rosanna lived

at 8 Eccles Street either alone or with her daughter Mary

Kate. For more on the Woods, see the note on the James

Joyce Online Notes website.