When Bloom recalls the death of his infant son in Calypso,

he twice thinks that the experienced midwife ("Lots of babies

she must have helped into the world") could tell at once that

the infant would not survive: "She knew from the first poor

little Rudy wouldn't live. Well, God is good, sir. She knew at

once." How, one wonders, could she have known that? And can

readers share in her omniscience by learning what killed Rudy?

Two chapters later, the novel offers a clue to the first

question: Rudy's skin looked purple. With no diagnostic

testing or autopsy having been performed, the second question

cannot be answered definitively. But the addition of another

clue—in Ithaca, we learn that Rudy died eleven days

after birth—suggests that he may have died of a congenital

cardiac defect known as Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome

(HLHS).

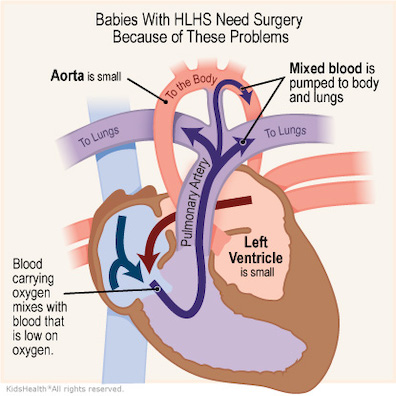

HLHS is characterized by a severely underdeveloped left

ventricle and ascending aorta, and by the presence of a septal

defect allowing blood to flow between the two atrial chambers.

In a normal heart, blood that has flowed from the right

ventricle to the lungs to take in oxygen returns to the left

atrium and moves from there to the left ventricle, which pumps

it through the aorta to the rest of the body. In the abnormal

development of HLHS the left ventricle is too small to pump

oxygenated blood to the body (in the worst cases, only a

slit), and the ascending aorta is likewise diminutive (in the

worst cases, only a thread).

With its normal passage blocked, the oxygenated blood in the

left atrium passes through the atrial septal defect always

found in cases of HLHS into the right atrium and thence into

the right ventricle, where it mixes with the oxygen-poor blood

that the veins have brought back to the heart from the body.

The pulmonary artery carries some of this mixed blood (shown

as purple in the illustrations) to the lungs, but some of it

passes to the rest of the body via the ductus arteriosus, a

fetal blood vessel connecting the pulmonary artery and the

aorta that, in utero, lets most of the blood bypass the

fluid-filled, not-yet-functioning lungs of the fetus. In

healthy babies the ductus arteriosus closes shortly after

birth.

As long as the fetus with a hypoplastic left ventricle

remains in the womb it is sustained by the oxygen it receives

from the mother's blood. As soon as the umbilical connection

is severed, however, the baby must depend solely on the poorly

oxygenated blood pumped from its right ventricle. Oxygen

saturation plummets to about 85%, resulting in marked cyanosis

(purplish skin). The decreased oxygenation delays the closure

of the ductus arteriosus, allowing adequate blood flow to the

body for a short while, but eventually this vessel does

close—typically in about 11 days. Blood flow is greatly

reduced, and death follows quickly. Without treatment, HLHS is

universally fatal.

The precise birth and death dates detailed in Ithaca

provide one indication that Rudy may have died from HLHS or

some other "ductal-dependent lesion" revealed by the closing

of the ductus: "birth on 29 December 1893 of second (and only

male) issue, deceased 9 January 1894, aged 11 days."

Another clue comes in Hades when Bloom sees a child's

tiny coffin and is reminded of his little boy's cyanotic

appearance: "A dwarf's face, mauve and wrinkled like

little Rudy's was. Dwarf's body, weak as putty, in a

whitelined deal box." Although the illustrations here

exaggerate the red color of oxygenated blood, the blue color

of venous blood, and the purple color of their mixing, the

three kinds of blood do display these distinctive colors. The

narrative itself exaggerates the cyanosis of Rudy's skin by

describing it as mauve, a rich

purple hue. The purple coloration must have been the trigger

for Mrs. Thornton's intuitive judgment that the baby was

suffering from a fatal condition.

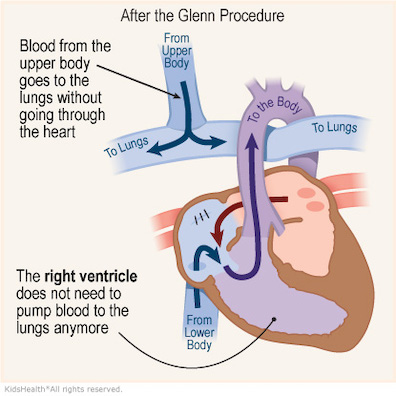

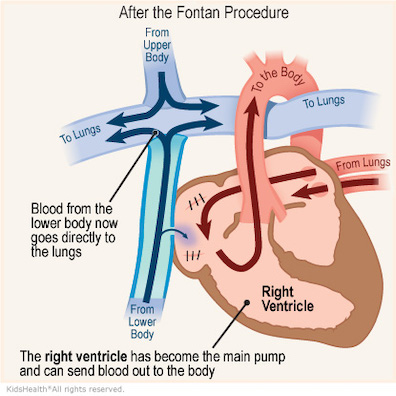

Today, there are three staged surgical procedures for

rebuilding these infants' malformed hearts: the multifaceted

Norwood procedure, generally performed in the first week of

life and fatal more than 10% of the time; the Glenn procedure

(Bidirectional Glenn Anastomosis),

usually done at about six months of age and carrying a much

lower surgical mortality risk of 1-3%; and the Fontan

Procedure, performed at 18-24 months with a comparably low

risk of death. The three operations are performed

successively, each building on the work of the former. They

are palliative, not curative, leaving the child with only a

single functioning ventricle.

Even with surgical and medical interventions, mortality and

morbidity from HLHS remain high. Children with the condition

typically suffer from incomplete brain development during

gestation and score in the low-normal range on IQ tests; other

somatic complications are commonplace. One study showed that,

a year after the Norwood Procedure, the mortality rate was

25%. Over time, survival rates increase. For children who

survive to the age of 12 months, long-term survival up to 18

years of age is approximately 90%. Even had the Blooms been

able to take advantage of these open-heart surgeries, their

lives as parents would not have been easy. But the development

of the three procedures lay many decades in the future. In

1904, HLHS was a death sentence.

Surrounded by large families, Joyce may have known of

infants who died at about 11 days of age, or his brief stints

as a medical student in Dublin and Paris could have

familiarized him with the deadly heart condition. Although

rare, HLHS is common enough to be known to all doctors: in the

U.S. the prevalence is approximately 2-3 cases per 10,000 live

births. HLHS accounts for 2-3% percent of all cases of

congenital heart disease and afflicts males approximately 1.5

times as often as females.