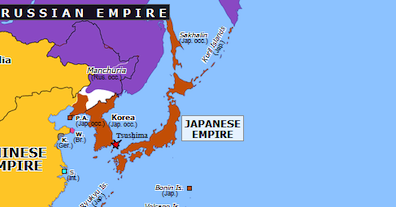

Tsarist Russia had been an expansionist power since the 16th

century and by the 19th century its empire was immense, ruling

well over 100 million people and reaching from Finland to

Crimea, Poland to Alaska, central Asia to the Arctic. Seeking

an ice-free port on the Pacific Ocean, the Russians expanded

into Manchuria and thereby encountered the rising Asian power

of Japan, which was expanding its own sphere of influence into

Korea and Manchuria. Diplomatic efforts to divide the

contested territories failed, and Japan attacked Russia's

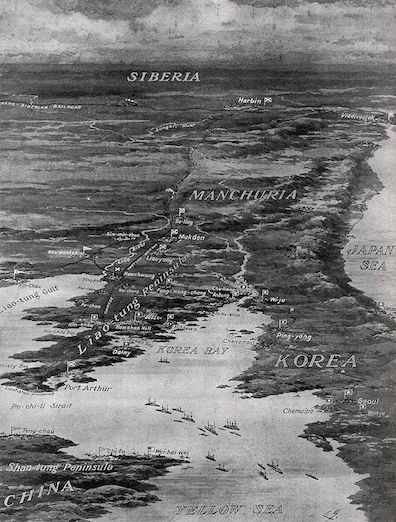

Eastern Fleet in February 1904. For the rest of that year an

arrogant Nicholas II declined overtures for an armistice and

arbitration, but his forces suffered defeat after defeat, and

in September 1905 he was forced to agree to a treaty mediated

by American president Theodore Roosevelt. Russia's

international influence dimmed, and a 1905 revolution at home

compelled the tsar to share power with a parliament—a first

step toward the disastrous revolution of 1917.

Although Britain had entered into a military alliance with

Japan in 1902 and must have taken some satisfaction in the

humiliation of its imperial rival, Irish nationalists too may

well have rejoiced, for different reasons. Nationalists in

other colonized regions—India, Indonesia, Indochina, the

Philippines, Poland—were inspired by the defeat of one of the

great European empires. Joyce appears to have been of the same

mind. Looking back from a time after Japan had secured

victory, he made people in 1904 Dublin relish the coming

Russian setback. In Calypso Leopold Bloom, himself

remembering a time before the start of the war, recalls Larry

O'Rourke saying, "Do you know what? The Russians, they'd

only be an eight o'clock breakfast for the Japanese." In

Cyclops Joe Hynes and the Citizen trade observations

about how "the markets are on a rise" because of "Foreign

wars." Says Joe, "It's the Russians wish to tyrannise."

Oxen of the Sun shows that other Dubliners have been

closely following the events in the Pacific: "Jappies? High

angle fire, inyah! Sunk by war specials. Be worse for him,

says he, nor any Roosian." At the beginning of the war,

in February 1904, some Russian battleships and cruisers had

been taken out of action by Japanese artillery shells that

descended at a "High angle" and penetrated the ships' lightly

armored decks. Gifford notes that these losses impelled the

Russian fleet to withdraw from fighting for several months

while repairs were made, and that "The Evening Telegraph,

16 June 1904, reported 'a renewal of activity on the part of

Russia's naval commanders' (though that renewal was to lead to

further Russian losses during the summer of 1904)." Joyce's

characters have been following news of the war, and their

slang suggests partisan identification with the enemy of a

bullying empire: "Inyah" or inagh, from the

Irish an ea, is a sarcastic Hiberno-English

expression meaning "Is that so?"

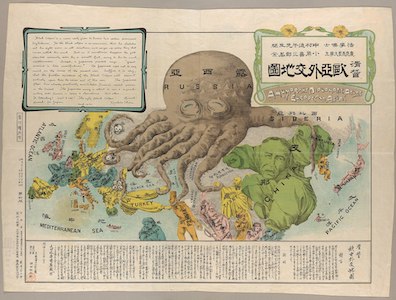

The Russians' troubles are linked with those of the English

in Eumaeus, when the proprietor of the cabman's

shelter predicts the collapse of the British empire: "But a

day of reckoning, he stated crescendo with no

uncertain voice—thoroughly monopolising all the

conversation—was in store for mighty England, despite her

power of pelf on account of her crimes. There would be a fall

and the greatest fall in history. The Germans and the Japs

were going to have their little lookin, he affirmed. The

Boers were the beginning of the end. Brummagem England was

toppling already and her downfall would be Ireland, her

Achilles heel." Irish public opinion had favored the Boers in

their valiant effort to resist British imperial expansion into

their lands, but they did not finally have sufficient

resources to defeat a great empire. In the shelter-keeper's

view, however, the growing naval power of Germany and Japan

poses a real threat to Britain's supremacy at sea, and Ireland

cannot be counted on to keep playing its role as the backbone

of the British army—a prediction that anticipates debates in

Ireland during World War I.

Circe maintains the link between Russia and England as

Stephen ponders a British soldier's proposal to "bash in your

jaw." He mockingly contrasts Darwinian realism with the bogus

idealism of a tsar and a king who present themselves as

"philirenists," a Hellenic coinage meaning "peace-lovers": "Struggle

for life is the law of existence but human philirenists,

notably the tsar and the king of England, have invented

arbitration. (He taps his brow.) But in here it

is I must kill the priest and the king." In Cyclops

the Citizen has contemptuously dismissed King Edward VII's wish to be

thought of as a "peacemaker" ("Tell that to a fool... There's

a bloody sight more pox than pax about that boyo"), and in

part 5 of A Portrait Stephen disdained the tsar's

proposals for international disarmament and arbitration ("MacCann began to speak with

fluent energy of the Csar's rescript, of Stead, of general

disarmament, arbitration in cases of international

disputes....").

Gifford notes that the tsar's "'peace rescript of 1898'

solicited petitions from 'the peaceloving peoples of the

world'"—people like McCann. The multi-national Hague

Conference of 1899 that followed from these efforts did not

achieve general or even limited disarmament, but it instituted

a body for "arbitration of international disputes and it began

to systematize international laws of war. It is something of

an irony that Nicholas II's peace crusade was a prelude to the

Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5. In retrospect the czar's

motivation appears to have been to stall for time so that

Russia could achieve an armament comparable to that of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire." Gifford's sense of "irony" applies

also to the English king: in 1908 and 1909 Edward twice met

with Nicholas to discuss peace, but their talks "seemed to

presage an alliance with Russia in aid of England's

intensifying naval and colonial competition with Germany." For

the imperial powers jostling for advantage in the years prior

to the Great War, idealism inevitably took a back seat to realpolitik.

Moral clarity was somewhat easier to come by for subjugated

peoples looking in from the outside.