Bloom thinks three times of a chain of barber shops called

"Drago's." The business was an actual one, as is almost always

the case in Ulysses, and the proprietors did have that

name. Adolphe Drago committed suicide in 1897, and in 1904 the

shops were owned and operated by his widow. Neither spouse

figures in the novel.

In Lestrygonians, as he is taking a brief jog down

Dawson Street to get from Duke Street to Molesworth Street on

his way to the National Museum and Library, Bloom sees a "dyeworks'

shopvan drawn up before Drago's." The 1904 Thom's

Directory lists an "Adolphe Drago, Parisian perfumer and

hairdresser," at 17 Dawson Street, as both Gifford and Slote

observe. Slote notes also that the directory lists a second

establishment at 36 Henry Street, a block or two northwest of

the General Post Office on Sackville Street. There is evidence

(details in a moment) that the Drago family lived above the

Henry Street shop. Other evidence indicates that there was a

third Drago business at 29 Eden Quay, two blocks east of

Sackville Street on the north bank of the Liffey. When Bloom

thinks in Calypso of "Drago's shopbell ringing,"

and when he recalls in Sirens that "the barber in

Drago's always looked my face when I spoke his face in the

glass" (because seeing someone's face makes it easier to

understand their words), he could be thinking of any of these

three establishments, or more than one.

But the Drago references involve an additional complication.

Slote observes that Thom's lists the proprietor of the

shops on Dawson Street and Henry Street as "Mrs Drago,

wigmaker and hairdresser" (p. 1857). He does not speculate

about the disparity between linking the two shops to "Adolphe

Drago" and identifying the proprietor as "Mrs Drago," but that

apparent contradiction can now be explained. Little was known

about the Dragos until recently––Vivien Igoe does not mention

them––but this year Senan Molony and Vincent Altman O'Connor

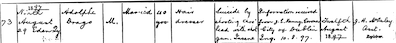

have uncovered pertinent information. In the Glasnevin

cemetery they have found a monument whose inscription reads,

In memory of my beloved

husband

Adolphe Drago, 36 Henry St..

Who died 9 August 1897 aged 40 years,

a kind and loving husband,

good father and a just man.

Sacred Heart of Jesus have mercy on his soul.

Also their dear son John Francis

Drago

who died 25 Feb. 1926.

Rest in peace.

Drago lived on Henry Street, then, and he died in 1897.

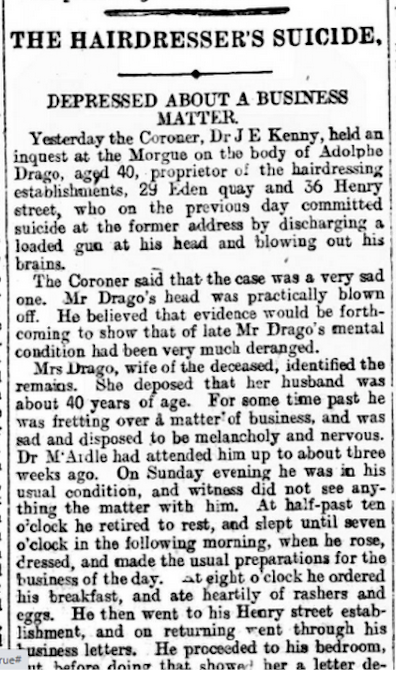

Contemporary documents identify the cause of death. The

coroner's official death certificate attributes it to "Suicide

by shooting thro' head with shot gun. Insane." An article in

the Irish Independent of August 11 goes into more

lurid detail, reporting that Drago died by "blowing out his

brains" and noting that "Mr Drago's head was practically blown

off." The article presents the coroner's finding that Drago's

"mental condition had been very much deranged." His widow

testified that "For some time past he was fretting over a

matter of business, and was sad and disposed to be melancholy

and nervous. Dr M'Ardle had attended him up to about three

weeks ago."

Neither spouse figures even slightly in Ulysses,

unless "the barber in Drago's" whom Bloom remembers was

Adolphe himself––and there is little reason to think that,

since Bloom speaks of him so impersonally and never mentions

him again. However, the Dragos' known biographical details do

hold interest in relation to themes explored elsewhere in the

novel. Mrs. Drago's proprietorship (the description of her as

"wigmaker and hairdresser" suggests that she was no mere

adjunct to her husband) allies her with other enterprising

Dublin businesswomen like "John

Wyse Nolan's wife." Her husband's struggles with mental

illness connect him to figures who seem to have a tenuous grip

on sanity, like Dennis Breen and Cashel Boyle O’Connor

Fitzmaurice Tisdall Farrell. His suicide in response to

chronic depression links him with Bloom's father.

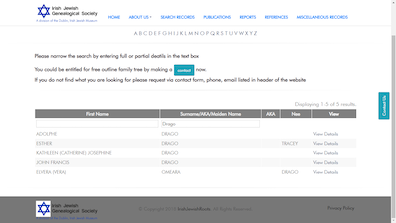

Finally, records in the Irish Jewish Genealogical Society

show that the Drago family were of Jewish descent. Bloom's

patronage of Drago's shop coheres with the way he seeks out

other Jewish merchants like Dlugazc

the butcher and Mesias the taylor. Although his father's

marriage to a Catholic woman, and his own, have engendered

separation from the tight Jewish community in south Dublin,

Bloom continues to circle back to his ethnic origins in a

spirit of curiosity, solidarity, and perhaps guilt.