Gifford glosses "To pot one's meat" as "crude slang for to

copulate," and that meaning resonates with the other

accidental sexual insinuations that assail Bloom as he stands

talking to M'Coy about Molly's upcoming singing tour.

("Who's getting it up?" "Part shares and part profits.")

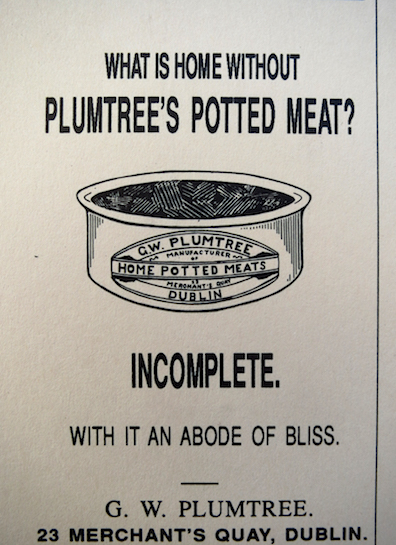

Plumtree's ceramic pots proclaimed that they contained "home

potted meats." Joyce's advertising jingle removes the word

"home" from the producer and gives it to the consumer:

What is home without

Plumtree's Potted Meat?

Incomplete.

With it an abode of bliss.

Later chapters, particularly

Lestrygonians, will

suggest that Bloom's home did reasonably approximate an abode of

bliss in the years when he and Molly were enjoying satisfying

carnal relations, and their marriage certainly did become

incomplete when those relations ceased after Rudy's death, early

in 1894.

As if to ensure that the jingle's taunting insinuations will

not go unnoticed, life later imitates the art of advertising.

Ithaca notes that, next to the "oval wicker basket

bedded with fibre and containing one Jersey pear" that Boylan

has had sent ahead of him to 7 Eccles Street, there is "an

empty pot of Plumtree's potted meat," no doubt one

of the contents of the basket. When Bloom climbs into bed

beside Molly, he discovers "the imprint of a human form, male,

not his," as well as "some crumbs, some flakes of

potted meat, recooked, which he removed." In the

course of repeatedly potting his meat Boylan has unpotted some

as well, enacting the novel's recurrent association of picnics

with sexual enjoyment.

The discussion of Molly's concert tour comes just after the Freeman

ad has impressed itself on Bloom's thoughts. Just before this,

he and M'Coy have been discussing Paddy Dignam's death, and

the ad reaches backward to encompass these associations as

well. "Potted meat" perfectly captures the spirit of Bloom's

meditations on burial in Hades, and in Lestrygonians

he reflects that the ad has acquired just such a

resonance by virtue of its placement. He seems to believe that

the gruesome association may not have been accidental. It is

the kind of stunt that an advertiser named M'Glade might try:

"His ideas for ads like Plumtree's potted under the

obituaries, cold meat department."

Later in Lestrygonians Bloom allows his imagination

to play with the equivalence between dead bodies and food, in

an associative sequence that leads logically to thoughts of

cannibalism: "Potted meats. What is home without

Plumtree's potted meat? Incomplete. What a stupid ad! Under

the obituary notices they stuck it. All up a plumtree.

Dignam's potted meat. Cannibals would with

lemon and rice. White missionary

too salty. Like pickled pork."

§ In Ithaca,

as Bloom once more contemplates bad ads, Plumtree's returns to

his mind as the worst of the worst. His thoughts veer from

objective specificity to fantastic wordplay: "Manufactured

by George Plumtree, 23 Merchants' quay, Dublin, put up in 4

oz pots, and inserted by Councillor Joseph P.

Nannetti, M. P., Rotunda Ward, 19 Hardwicke street, under the

obituary notices and anniversaries of deceases. The name on

the label is Plumtree. A plumtree in a meatpot, registered

trade mark. Beware of imitations. Peatmot. Trumplee. Moutpat.

Plamtroo." Not for the first time in Ithaca, the

authoritative air of objective fact here masks a fictive

falsification, for Joyce has transformed an English business

concern into an Irish one.

In "Plumtree’s Potted Meat: The Productive Error of the

Commodity in Ulysses," published in Texas Studies in

Literature and Language 59.1 (Spring 2017): 57-75,

Matthew Hayward observes that George W. Plumtree, 49 years old

at the time of the 1901 census, was a "Manufacturer of

Preserved Provisions" in Southport, England (61). The Census

of Ireland in that year, and again in 1911, showed no people

named Plumtree. Surviving Plumtree's pots bear one of two

addresses in Southport, either 184 Portland Street or 13

Railroad Street (apparently the business moved at some point).

From these English addresses, the firm shipped its products to

a small agency in Dublin, which in turn distributed them to

retailers. In 1904 that office was located at 23 Merchants'

Quay.

Thom's Dublin Directory misleadingly identified the

Dublin wholesale operation as "Plumtree, George W. potted meat

manufacturer," so Joyce's perpetual reliance on Thom's may

have caused him to unwittingly list the wrong address. But

Hayward argues that he must also have been using other

sources, probably contemporary advertisements, because Thom's

makes no mention of the 4 oz. pots or the "Home Potted Meats"

name. Joyce might even have been looking at an actual pot: in

an endnote, Hayward records the fact that in 1905 he asked

Stanislaus "to bring a big can of tinned meat" with him when

he came to Trieste (Letters 2:121). Both the pots and

surviving early 20th century ads clearly list an address in

Southport, England.

If Joyce did deliberately move Mr. Plumtree's business to

Dublin, then the potted meat motif must be viewed in the

context of the novel's many reflections on shipping beef and

sheep to England and the loss of Irish home industry under

British imperial rule. Englishmen bought Irish livestock

tax-free. Businesses like Plumtree's created added value by

manufacturing pots of ground-up unidentified meat parts and

marketing them as home cooking, and shipped them back across

the sea to Irish consumers, once again under favorable tariff

arrangements. Specifying an address on Merchants' Quay for the

business, Hayward notes, would "seem to contain the product in

the domestic Irish economy, appearing to fulfill the terms of

the 'Buy Irish' movement that Joyce at one time endorsed as

the best hope for Irish regeneration (Joyce, Letters

2:167)" (61).

But Plumtree's was not a home industry, and if the Dublin

address is a calculated fiction then the novel is protesting

the colonial economic arrangements which resulted in Ireland

buying back its own meat, at a markup, from England. This

strategy would cohere with Joyce's invention of a catchy ad

promising improvement in people's home lives if they eat the

right kind of food. Extending the scholarly work of Anne

McClintock and Thomas Richards, Hayward describes how British

businesses used imperial patriotic fervor to sell products

like Pears' soap and Bovril beef tea through ads implying that

their consumption helped spread enlightened, scientific,

health-conscious civilization. He connects "The commodity's

promise of social improvement" to a phrase in Joyce's

fictional ad, "an abode of bliss" (70).

Hayward does not, however, make one final connection that

would enable a wholly new reading of Joyce's mock ad,

consistent with the novel's other analogies between the

misrule in Bloom's home on Eccles Street and advocacy of Home

Rule for Ireland. The entire four-line text can be read as a

comment on the atrophy of Irish economic enterprises under

British colonial rule. What is our Irish home without

industries like Plumtree's? Incomplete.