Pádraic, or Patricius as he calls himself in his Latin Confessio

and a single Latin letter, was not Irish at all but

Romano-British, son of a decurion (probably a civic tax

collector) named Calpurnius in an unknown town named Bannavem

Taburniae. He was probably born in the late 380s AD and

probably died in the early 460s. Raiders enslaved him as a

teenager and brought him to Ireland, where he herded sheep for

six years before escaping, probably back to his home in

Britain. According to a legend credited by Stephen in Ithaca

he returned to Ireland in 432, "sent by pope Celestine I,"

and effected "the conversion of the Irish nation

to christianity from druidism."

Some of this appears to be true: the Annals of Ulster,

compiled no earlier than the mid-6th century, date Patrick's

return to 432. But the legend misleadingly conflates Patrick

with the other prominent missionary to Ireland of the period,

Palladius. According to a famous chronicle by Prosper of

Aquitaine, Pope Celestine sent Palladius to Ireland in 431 to

become bishop to a community of Christians––suggesting that

the conversion process was already well under way. Patrick,

for his part, says in the Confessio that he

returned to Ireland after receiving a vision of people writing

from Ireland, begging him to come back and convert them.

(Thanks to Cian Lyons for his expert help with the details of

this summary.)

Fittingly for an ad salesman, Bloom seems most interested in

how this talented missionary succeeded so well at persuading

the violent pagan warriors of the island to accept the

Christian dispensation—a sales job that has never quite worked

on Bloom himself. In Lotus Eaters he thinks, "Clever

idea Saint Patrick the shamrock." According to legend,

Patrick used one of these three-leaved clover shoots to

illustrate the Christian doctrine of the Trinity. In Lestrygonians

Bloom gets off one of his better jokes of the day when he

thinks of another of Patrick's adventures in sales: "That

last pagan king of Ireland Cormac in the schoolpoem choked

himself at Sletty southward of the Boyne. Wonder what he

was eating. Something galoptious. Saint Patrick converted

him to Christianity. Couldn’t swallow it all however."

Bloom is mistaking one pagan king for another, under the

influence of a 19th century poem that he learned in school.

The great Cormac, son of Art, reigned during the 3rd century,

so Patrick could not possibly have interacted with him, but

legend holds that he did convert to Christianity, thereby so

angering the druid priests of

the existing faith that they cursed the king and caused him to

choke on his food. According to the Annals of the Four

Masters, it was a salmon bone. Bloom's revery is prompted by

watching the diners in the Burton "Working tooth and jaw" and

thinking, "Don't. O! A bone!"

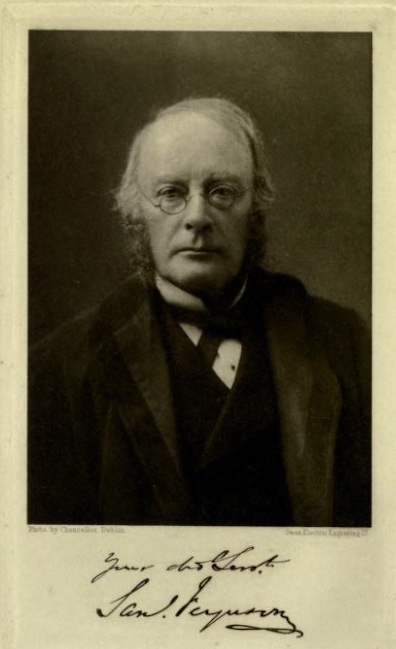

The poem by Sir Samuel Ferguson (1810-86), 28 quatrains on

"The Burial of King Cormac," was first published in Lays

of the Western Gael in 1864. It says that Cormac "choked

upon the food he ate / At Sletty, southward of the Boyne."

The poem improbably relates that, as the king choked to death,

he managed to find breath enough to say, "Spread not the beds

of Brugh for me, / When restless death-bed's use is done: /

But bury me at Rossnaree, / And face me to the rising sun. /

For all the kings who lie in Brugh / Put trust in gods of wood

and stone; / And 'twas at Ross that first I knew / One,

unseen, who is God alone."

The ruler who couldn't quite swallow the saint's teachings,

as opposed to his dinner, was Leary (Laoghaire), who according

to the Four Masters had been High King for four years when

Patrick arrived in 432. He did not agree to convert but

allowed Patrick to proceed with his missionary work. In Ithaca

Bloom somehow finds occasion to recite his confusion of the

two kings to Stephen, who sets him straight on Cormac being

the "last pagan king": "Bloom assented covertly to Stephen’s

rectification of the anachronism involved in assigning the

date of the conversion of the Irish nation to christianity

from druidism by Patrick son of Calpornus, son of

Potitus, son of Odyssus, sent by pope Celestine I in the year

432 in the reign of Leary to the year 260 or thereabouts

in the reign of Cormac MacArt († 266 A.D.), suffocated by

imperfect deglutition of aliment at Sletty and interred

at Rossnaree."

As it happens, Stephen has actually been thinking earlier in

the day about such historically impossible meetings of great

figures. In Scylla and Charybdis he muses about "Oisin

with Patrick." Medieval oral traditions held that Oisin

(Oisín), warrior-poet son of Finn MacCool (Fionn MacCumhail)

and historian of the legendary Fenians (Fianna), survived for

200 years after the end of the heroic age because he left with

his bride Niamh for her land of Tír na nÓg, a place off the

western coast of Ireland where time has no meaning or reality

and nothing ages. When he returned to visit his father in

Ireland, he found Fionn and his entire way of life gone, and

he himself became old, blind, and enfeebled, but there was

Patrick, eager both to teach Oisin the true faith and to learn

about the Fianna from him.

In some Christian tales Patrick succeeds in converting Oisin,

but in pagan versions Oisin more than holds his own,

vigorously defending his pagan beliefs and values against

"Patrick of the closed mind" and his small-minded religion.

None of Stephen's thoughts about the meeting of the two men

are given, but since he thinks of it in relation to his own

Parisian encounter with a truculent John Millington Synge, it

seems likely that he is recalling the more argumentative

versions.

Other famous legends about Patrick come up in the chapter

most associated with Irish nationalism, Cyclops. Patrick

appears in its long list of saints and also in the mention of

"Croagh Patrick," the holy mountain on the ocean's edge

in County Mayo where the saint is supposed to have fasted for

40 days and expelled all of Ireland's snakes, which are

sometimes read allegorically as representing the druids. The

Citizen seems to be thinking of this lore when he vituperates

Bloom, another representative of a false faith, as a poisonous

"thing" to be driven out: "Saint Patrick would want to land

again at Ballykinlar and convert us, says the citizen, after

allowing things like that to contaminate our shores."

Ballykinler, a village 30 miles south of Belfast in Ulster's

County Down, sits on Dundrum Bay, which is one reputed site of

Patrick's arrival in Ireland.

Cyclops also mentions "S. Patrick's Purgatory,"

another geographical site associated with the saint's

miracles. This one is in County Donegal, in the far northwest.

Station Island in Lough Derg contained a deep pit or "cave"

which Christ, in a vision, showed Patrick to be an entrance to

Purgatory. The belief arose that pilgrims who spent a day and

a night in this pit would experience the effects of Purgatory,

suffering the torments appropriate to their sins and tasting

the joys of salvation. From the 12th century to the 17th,

pilgrims thronged to the site. The practice was revived in the

19th century, accounting for its mention in Cyclops,

and it continues today, as evoked in Seamus Heaney's long

collection Station Island (1984).

In the Middle Ages pilgrims typically went first to Saints

Island, a larger piece of land near the shore, and then rowed

to Patrick's island. The 17th century map reproduced here

shows boatloads of pilgrims approaching the shores of Station

Island and the "Caverna Purgatory," which today is covered by

a mound supporting a bell tower for the adjacent church. The

filling in of the cave would seem to have occurred in the

1650s, when Oliver Cromwell's soldiers desecrated the site in

his campaign to suppress Irish Catholicism. The map with its

indication of a cave was published in 1666, however, so

perhaps the date is later. In any case, pressures to shut down

the pilgrimage site had been building ever since the papacy

issued bans against it just before and after the year 1500.

Cyclops makes brilliant comedy out of another famous

aspect of Patrick's hagiography: his saint's day, March 17.

This is traditionally regarded as the date of his death,

though no reliable records exist. The 19th century poet and

songwriter Samuel

Lover wrote a bit of comical verse making fun of the

arbitrary date, but he connected it to the saint's birthday.

According to "The Birth of S. Patrick," the first factional

fight in Irish history was over the question of whether

Patrick was born on March 8 or March 9. One Father Mulcahy

persuaded the combatants to combine the two numbers and settle

on March 17. Having done so, "they all got blind drunk—which

complated their bliss, / And we keep up the practice from that

day to this."

Joyce turns this contention over dates into a brawl with

assorted deadly weapons between members of the Friends Of The

Emerald Isle who have come to witness the execution: "An

animated altercation (in which all took part) ensued among the

F. O. T. E. I. as to whether the eighth or the ninth of

March was the correct date of the birth of Ireland's

patron saint." A Constable MacFadden is summoned and

proposes "the seventeenth of the month as a solution equally

honourable for both contending parties." The quick acceptance

of the policeman's proposal seems to have much to do with the

fact that he is described as "The readywitted nine footer."

Joyce continued his engagement with the mythology of Saint

Patrick in Finnegans Wake. In the summer of 1923 he

worked on a sketch of "St Patrick and the Druid" inspired by

stories of the saint's encounter with King Leary and his

archdruids, who were encamped on the Hill of Tara. Patrick is

said to have camped on the nearby Hill of Slane and built a

paschal fire on the night before Easter, alarming the druids

who held that all fires must be extinguished before a new one

was lit on Tara. They told the king that if this one was not

put out it would burn forever. Traditionally, this story is

told as a Christian victory, but in Joyce's sketch, which he

referred to as "the conversion of St Patrick by Ireland," a

druid named Berkeley

meets Patrick in the presence of the king and does all the

talking, teaching the Christian his idealistic theory of light

and color by discussing the "sextuple" (or, alternately,

"heptachromatic sevenhued") colors displayed in King Leary's

person (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet), all

of which turn out to be shades of botanic green.

This sketch fed into several parts of the Wake, including its

spectrum of rainbow colors and the phrase on its first page,

"nor avoice from afire bellowsed mishe mishe to tauftauf thuartpeatrick."

Joyce reworked the sketch extensively near the end of the

book. On pp. 611-12, the archdruid Balkelly (a Shem figure)

and "his mister guest Patholic" (Shaun) continue the

discussion of light, color, and vision. The druid again uses

"High Thats Hight Uberking Leary" as the example of

his impractical way of seeing, but this time Patholic has the

last word, invoking the sun of everyday seeing and the Great

Balenoarch (the Italian for rainbow is arcobaleno) of

the world's apparent colors.

In a 17 March 2015 blog post that discusses the presence of

Patrick and the druid in the Wake, Peter Chrisp concludes by

observing how important this saint was to Joyce. The Swiss

writer Mercanton, Chrisp observes, talked to Joyce as he

basked in the late sunlight one evening on the Quay de Lutry.

Mercanton recorded that he "spoke of St Patrick, whose

intercession was indispensable if he was to complete the

book." Joyce said, "I follow St Patrick... It is the title of

an erudite book by my friend Gogarty... Without the help of my

Irish saint, I think I could never have got to the end of it."

Chrisp ends by noting that "Gogarty's book was found on

Joyce's desk after his death."