When Bloom sees a cat basking on the warm window sill of a

house, he recalls that "Mohammed cut a piece out of his mantle

not to wake her." Mantle here means a cloak or robe, not the

fireplace ledge (sometimes spelled the same way) that could be

called up by the image of the "warm sill." The story, one of

many thousands of hadith, traditional reports of the

words and deeds of the Prophet, holds an obvious appeal for

Bloom, who likes cats and has just thought, "Pity to disturb

them."

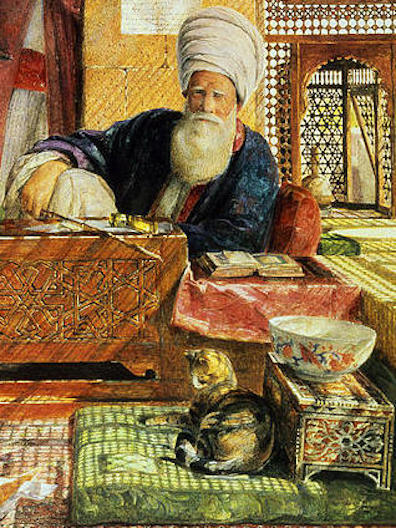

The best-known anthology of hadith is the Sahih

al-Bukhari, compiled by a Persian scholar named

Muhammad al-Bukhārī in the 9th century and revered by Sunni

Muslims. It has several passages referring to a woman who was

put in Hell because she imprisoned a cat until it died of

hunger, but none about the Prophet's act of kindness. Other

9th and 10th century collections, however, report that

Muhammad's favorite cat, Muezza, was sleeping on his robe one

day when the call to prayer came. Instead of waking her, he

cut off the sleeve of the robe. Islamic texts contain many

other encouragements to be kind to cats.

Bloom's sympathetic impulse toward this cat counts not only

as one more instance of oriental exoticism in Lotus Eaters,

but also as one more meditation on lotus-like states of

blissful relaxation. Indeed, nearly all of Bloom's thoughts of

the Mideast in this chapter (Jesus

at dusk, the excluded peri,

Mohammed and his cat) and also the Far East (lazy Cinghalese,

a reclining Buddha,

opium-smoking Chinese) can be read as efforts to project

himself out of his current mental struggles to a place where,

as Stephen thinks in Proteus, "Pain is far."