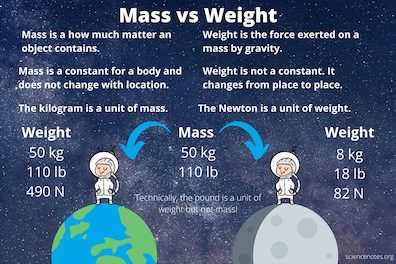

It is essentially correct, if a little imprecise, to say that

"the force of gravity of the earth is the weight."

According to the law of universal gravitation formulated by

Isaac Newton in 1686, all objects with mass attract one

another by a force that decreases in proportion to the square

of the distance between them. Any two objects will be drawn

more or less powerfully toward one another depending on how

much mass each has and how much distance separates them. This

pulling force is experienced as weight. A body with more mass

has more weight and a less massive one has less, but if they

were not pulled by the earth (or some other object) neither

would have any weight at all. On the Moon, as experience has

now confirmed, a human body will weigh less because of the

planet's lesser mass, even though its own mass remains the

same. Mass is an absolute quantity, but weight is a relative

one.

The second teaching that Bloom recalls, "Thirtytwo feet

per second per second," is a formula for describing

acceleration. In a vacuum, with no friction to slow its

descent, a dropped object will reach a speed of about 32 feet

per second (taken to three decimal points, 32.174) after one

second has passed. After two seconds it will be moving at a

rate of 64 ft/sec, after three 96 ft/sec, and so on. Like

weight, this steady gain in the velocity of falling bodies is

caused by the pull of the earth's gravity. (Gravitational

acceleration obeys different mathematical laws from those

governing weight. The speed of falling bodies increases in

direct proportion to time, and only as the square root of

distance. But as the third image here illustrates, it has a

direct mathematical relation to weight. Weight = mass x

gravitational acceleration.)

These scientific ideas linger in Bloom's mind throughout the

day. Weight's relativity seems to contribute to his

phenomenological ways of thinking about it, most of which have

to do with the feeling of being oppressed (weighed down). In Hades

the narrative's account of men hoisting Paddy Dignam's coffin

gives way, via a pun, to Bloom's subjective impressions: "The

mutes shouldered the coffin and bore it in through the gates.

So much dead weight. Felt heavier myself stepping out of

that bath." In Lestrygonians he regards women's

loss of weight post-partem as partly mental: "How flat they

look all of a sudden after. Peaceful eyes. Weight off

their mind." Nausicaa finds him thinking about

women's feelings of weight once again, this time in relation

to menstruation: "Devils they are when that’s coming on them.

Dark devilish appearance. Molly often told me feel things

a ton weight." In such cases weight is not something to

measure; it is felt. In the book's most subjective

chapter, Circe, Bella's hoof says to Bloom, "Smell my

hot goathide. Feel my royal weight," and shortly later

Bella herself commands, "Footstool! Feel my entire weight."

Bloom also thinks about bodies gaining speed as they fall.

When he throws the "Elijah is coming" throwaway into the river

in Lestrygonians, the downfall sounds more precipitous

than any that a piece of paper, slowed by friction, would

experience: "He threw down among them a crumpled paper ball. Elijah

thirtytwo feet per sec is com." In this despondent

chapter one may imagine that Bloom feels some gloomy

identification with the discarded Jewish prophet. In Circe

that impression is confirmed as he reenacts the plunge into

the waters of the Liffey, standing on a cliff's edge on Howth

Head: "(He gazes intently downwards on the water.) Thirtytwo

head over heels per second. Press nightmare. Giddy Elijah.

Fall from cliff. Sad end of government printer's clerk.

(Through silversilent summer air the dummy of Bloom, rolled

in a mummy, rolls rotatingly from the Lion's Head cliff into

the purple waiting waters.)" But fantasy can also

reverse the effects of gravity. At the end of Cyclops

Bloom's victory over the Citizen is celebrated with a

rocket-launch version of Elijah's ascension into heaven, "at

an angle of fortyfive degrees...like a shot off a shovel."

These encounters with gravity are mere fantasies, but in Ithaca

Bloom's body actually does fall through space. Finding

that he has no key to his house, he climbs over the area

railing, hangs suspended from the bars by his hands, and

consents for "his body to move freely in space by separating

himself from the railings and crouching in preparation for the

impact of the fall." The narrative asks, "Did he fall?" and

answers in the affirmative: "By his body’s known weight of

eleven stone and four pounds in avoirdupois measure."

"Did he rise uninjured by concussion?" Answer: "he rose

uninjured though concussed by the impact."

"By his body's known weight" implies that his weight is

somehow responsible for the speed of his fall. In a limited

and inexact sense this is true, because a body would not fall

if it did not have mass. But as the science lesson above

should make clear, weight is the product of gravitation, not

the cause, so no body will accelerate in proportion to its

weight, and the difference in mass between a heavy

human being and a light one is so relatively miniscule that it

would have no measurable influence on its gravitational

attraction to the earth. One of the milestones in the history

of understanding gravitational acceleration came in 1604 when

Galileo found that, counter-intuitively, objects of different

weights will accelerate at exactly the same rate, providing

friction is minimized. Bloom's body will not accelerate faster

or slower than any other.

However, it will accelerate with every second of time elapsed

and every foot of distance traveled. Evidence suggests that,

depending on one's age and physical condition, the velocity

needed to damage human limbs is achieved after a fall of about

20 feet. Joyce's narrative precisely specifies the harrowing

distance that Bloom's fall will cover: "two feet ten inches."