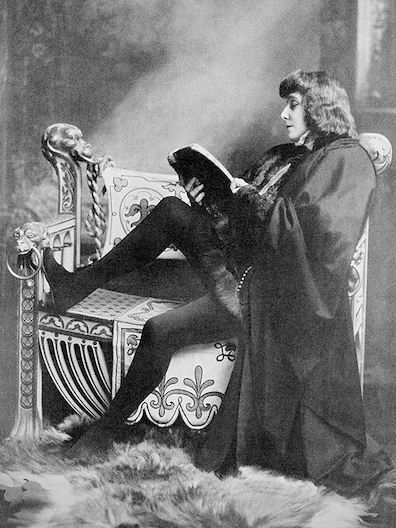

§ "Hamlet

she played last night. Male impersonator":

Bloom thinks this of Millicent

Bandmann-Palmer, who did perform in the play at the Gaiety Theatre on June

15. Gifford notes that a review of the show in the next day's

Freeman's Journal mentioned that she acted the

principal role and "to say the least sustained it creditably."

Strange as it may seem today (perhaps—it is becoming common

again in the 21st century), such cross-gender casting was a

frequent practice in 1904. Just as theater companies in

Shakespeare's time cast boys in women's parts because women

were viewed as inferior creatures and legally barred from

London's stages, late 18th and 19th century theater companies

often cast women in men's parts because beloved female actors

could find relatively few substantial female roles in

Shakespeare's plays. The conversion of Shakespeare's men into

"breeches parts" or "pants roles" (terms also commonly used in

opera) had become increasingly frequent by the end of the 19th

century.

In an article titled "Tragedy, Gender, Performance: Women as

Tragic Heroes on the Nineteenth-Century Stage," Comparative

Literature 30.2 (1996): 135-57, Anne Russell ably

summarizes this history. Some of the performances she mentions

were so influential that for decades afterward women continued

to be cast in the same part: Sarah Siddons' Hamlet (1776-81),

Ellen Tree's Romeo (1832), Patricia Horton's Fool in King

Lear (1838). For theatrical producers of the time, the

Danish prince seemed particularly suited to female

interpretation, and "At least fifty English and American

actresses played Hamlet in the latter part of the nineteenth

century: Charlotte Cushman, Emma Walker, Fanny Wallack, Clara

Fisher Maeder, Alice Mariott, Julia Seaman, Winetta Montague,

and Millicent Bandmann-Palmer...who played Hamlet hundreds of

times" (143). The tradition reached a kind of apex in Sarah

Bernhardt's famous 1899 performances.

§ But "Perhaps

he was a woman": Bloom's focus shifts from seeing the

actress playing Hamlet as a male impersonator to wondering if

the character himself (or herself) somehow is (or was) a

woman. His source here is a 19th century American literary

critic named Edward Payson Vining whose thoughts about Hamlet

both reflected and influenced the female portrayals happening

on stage. In The Mystery of Hamlet; An Attempt to Solve an

Old Problem (1881), Vining argues that Queen Gertrude

gave birth to a girl. With war raging between Denmark and

Norway she dressed her child as a boy in hopes of ensuring her

offspring's succession to the throne. Vining devised this

backstory to explain Hamlet's feminine qualities: instead of

showing "the energy, the conscious strength, the readiness for

action that inhere in the perfect manly character" (46), the

prince spends his time deploring drunkenness, pondering

morality and religion, and emotionally leaping into graves.

This all seems pretty unlikely, as (leaving aside the gender

stereotypes) Shakespeare never alludes to any of Hamlet's

upbringing except his university education, and never in all his

soliloquies does the prince suggest that, in addition to

concealing a murderous intent behind an antic disposition, he is

also concealing a female nature behind a male appearance. In

Twelfth

Night, which he wrote at about the same time as

Hamlet,

Shakespeare got a lot of dramatic mileage out of a female

cross-dresser's self-disclosures to the audience, her public

embarrassments when male violence or heterosexual desire is

called for, and the sympathies she finds for both genders as a

result of her disguise. But Viola's trouser role as Cesario, and

Rosalind's as Ganymede, and Imogen's as Fidele—all of them men

playing women playing men—do arguably encourage a literary

critic to look around for further cases of gender-bending. In

that context, Vining's conceit of a woman dressing up as a man

to make her way in a male world does not seem so very fantastic.

Nor was his quasi-biographical way of reading a play all that

unusual for his time. Literary critics in the second half of the

19th century often studied leading characters in Shakespeare's

plays as if they might be real people, jumping off from mere

dialogue to sketch detailed psychological portraits and

inferring life histories that began well before the opening

scene. (The most famous work of this kind, A. C. Bradley's

Shakespearean

Tragedy, was published in the year in which

Ulysses

is set, 1904.) Such an approach feels dated now, but it was all

the rage in the Victorian and Edwardian era. It becomes truly

untenable only if one begins to think of Shakespeare's

characters as actual people. Bloom seems to flirt with this

absurdity by thinking that Hamlet "

was a woman," but he

maintains comic detachment in the following sentence: "

Why

Ophelia committed suicide."

Eglinton has his own wry detachment: "The bard's

fellowcountrymen," he supposes, "are rather tired perhaps of

our brilliancies of theorising. I hear that an actress

played Hamlet for the fourhundredandeighth time last night

in Dublin. Vining held that the prince was a woman. Has

no-one made him out to be an Irishman?" One Irishman whose

brilliancies of theorizing he is aiming at is Stephen, who has

been ransacking recent biographies of Shakespeare to construct

a pseudo-critical account of the playwright's life just as

fantastic as Vining's portrait of Hamlet. But seeing as how

Eglinton, Lyster, Best, and Mulligan are always throwing out

alternatives to Stephen's preferred authorities and

explanations, Joyce may be evoking the Hamlet-was-a-woman

theory here for a second reason. Vining's account of a

character ill-suited to a masculine world of violent action

sounds very much like the view of Hamlet advanced by Stephen's

argumentative opponents: "The beautiful ineffectual dreamer

who comes to grief against hard facts." Stephen's Hamlet is

much more the murderous man of action.