In 1904 James Joyce walked into the pharmacy on Lincoln Place and

quizzed the proprietor, Frederick William Sweny, about

his business. This minor research foray no doubt gave him some

material for Bloom's reverie about the stuff on the shelves:

"Aq. Dist. Fol. Laur. Te Virid. Smell almost cure you like the

dentist's doorbell. Doctor Whack. He ought to physic himself a

bit. Electuary or emulsion. The first fellow that picked an

herb to cure himself had a bit of pluck. Simples. Want to be

careful. Enough stuff here to chloroform you. Test:

turns blue litmus paper red. Chloroform. Overdose of laudanum.

Sleeping draughts. Lovephiltres. Paragoric poppysyrup bad for

cough. Clogs the pores or the phlegm. Poisons the only cures.

Remedy where you least expect it. Clever of nature." Some of

the details here are neutral enough, but a thread of Odyssean

peril runs through the paragraph.

At the dawn of the 20th century pharmacology still relied

heavily on traditional herbal remedies, a fact which makes

Bloom think of the daring of the prehistoric humans who first

experimented with consuming potent leaves, berries, barks, and

roots. Pharmacies were stocked with numerous bottles, boxes,

and wooden drawers holding such ingredients. They were the "Simples"

which pharmacists compounded to make their various

preparations. (The OED notes that in medicine the term

means "Consisting or composed of one substance, ingredient, or

element...esp. natural or organic.") Many such herbal

ingredients in pharmacists' shops were quite unremarkable. The

trade abbreviations that sound so daunting in Latin (like the

phrases that Bloom has just heard used in the church) actually

refer to very ordinary household substances. "Aq. Dist."

or Aqua distillata is Latin for distilled water. "Fol.

Laur." or folia laurea are bay leaves,

picked from the laurel tree. "Te Virid" is the (or

te) viridis, green tea.

Other ingredients, however, were more powerfully productive of

precise chemical effects in the body. "Chloroform"

(trichloromethane) was first synthesized in the 1830s, and by

1850 it was being put to medical use as an anaesthetic. (Queen

Victoria used it in childbirth, popularizing that practice.)

It is not clear whether chloroform is being marketed in

Sweny's shop; Bloom thinks only that there is "Enough stuff

here to chloroform you." But "laudanum" was a staple of

all Victorian pharmacies. This tincture of powdered opium

mixed with alcohol had been used since the 17th century as a

painkiller and by the late 19th century made up such a large

part of pharmacy sales (unregulated and often self-prescribed)

that addiction had become a widespread problem. Well more than

half of addicts were women, owing to laudanum's great

effectiveness in treating menstrual cramps. Bloom thinks of

the danger of "Overdose," and a moment later he

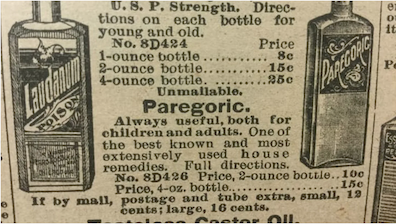

reflects, "Paragoric poppysyrup bad for cough."

Paregoric is another, less potent tincture of powdered opium

(hence "poppysyrup") that had been used since the early 18th

century to treat cough, pain, and diarrhea, particularly in

children.

Through all of this consideration of pharmaceutical

ingredients Bloom loosely threads his layman's inexact

impressions of the business. He has evidently decided from his

own experience of raising a child that paregoric is not an

effective cough remedy. He thinks of "Sleeping draughts"—whether

or not he is still thinking of opium products here is unclear,

but laudanum was sometimes recommended as a soporific for

children—and also of "Lovephiltres." The OED defines

"philtre" as "A potion or drug (rarely, a charm of other kind)

supposed to be capable of exciting sexual love, esp. towards a

particular person." Bloom recalls from high school chemistry

class that acid "turns blue litmus paper red," though

this information is irrelevant to chloroform, which has a

neutral pH. And he knows that pharmaceutical compounds can

take the form of "Electuary or emulsion," the former

mixing powdered agents with some sweet ingredient like honey

to improve the taste, the latter suspending minute droplets of

a non-soluble liquid agent in water.

In this paragraph Bloom also meditates on the ingestion of

potent chemicals in a way that suits the Lotus Eaters

chapter's larger preoccupation with escaping reality. He

thinks about drugs (unspecified, but they would clearly

include laudanum) that people take to alter their mental

states: "Drugs age you after mental excitement. Lethargy

then. Why? Reaction. A lifetime in a night. Gradually

changes your character." His thoughtful prudence here

marks him as an Odysseus figure who can resist the lure of the

lotus.

But even his thoughts about properly therapeutic drugs are

tinged with an awareness of danger. Bloom's reflections on how

perilous it is to sample wild plants and to "Overdose" on

medicines lead him to an often-repeated maxim about drugs and

poisons: "Poisons the only cures. Remedy where you least

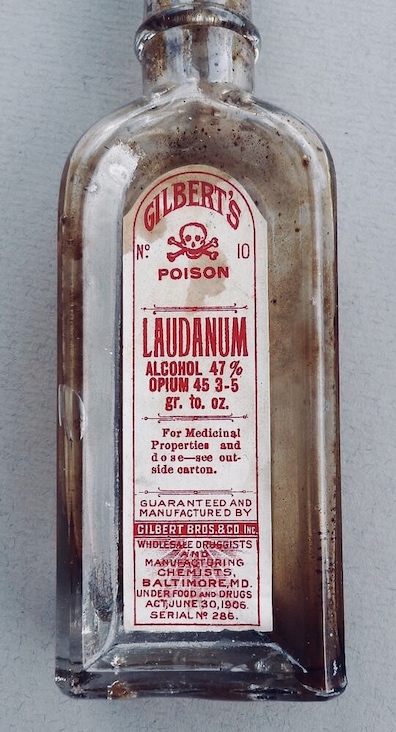

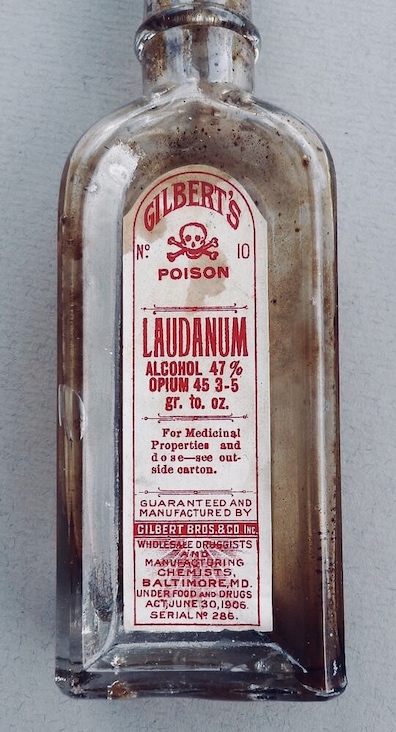

expect it. Clever of nature." (Laudanum labels at this

time often announced that the contents were "Poison," and

reinforced the warning with a skull and crossbones.)

Throughout this paragraph, the foray into Sweny's pharmacy

acquires the character of Homer's stories about men venturing

into unknown and highly dangerous places.

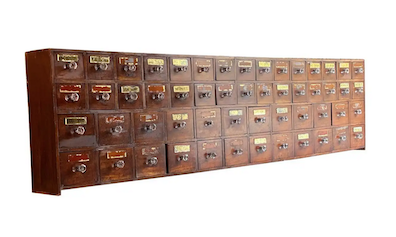

Adam Hart's recreation of the shelves of a

19th century pharmacy. Source: pixels.com.

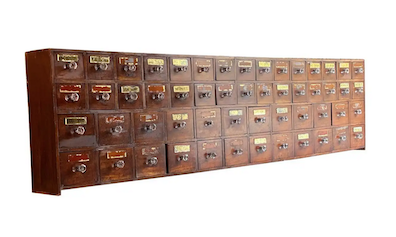

Wooden drawers for herbal simples made for a

Victorian pharmacy ca. 1870. Source: www.1stdibs.com.

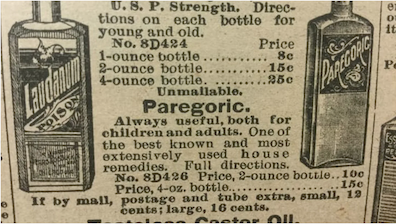

Laudanum and paregoric for sale in a 19th

century Sears catalogue. Source: www.mentalfloss.com.

American laudanum bottle from the early 1900s

marked with the word "Poison" and a skull and crossbones.

Source: imgur.com.