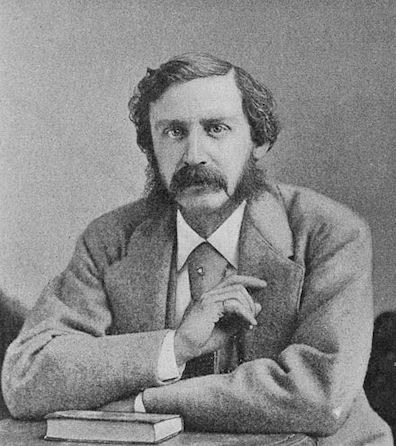

In 1870, while living in northern California, Bret Harte

published a narrative poem titled Plain Language from

Truthful James that sought to undermine the racial

prejudice shown toward Chinese workers in the western U.S.

Quickly gaining fame, the poem was republished at least eight

times in east-coast journals under the title The Heathen

Chinee.

The poem begins with the eponymous James struggling in his

rough-hewn and not very intelligent way to "explain" in

"plain" language what is so "peculiar" about the Chinese:

Which I wish to remark,

And my language is plain,

That for ways that are dark

And for tricks that are vain,

The heathen Chinee is peculiar,

Which the same I would rise to explain.

The speaker proceeds to tell how he and his friend Bill Nye sat

down to a game of euchre with a Chinese man. Ah Sin's smile was

"childlike and bland," and the whites assumed that "He did not

understand" the game, so they expected to easily take his money,

especially as Bill's sleeve was "stuffed full of aces and

bowers, / And the same with intent to deceive." But Ah Sin

shocked them by playing quite well, and at last "he put down a

right bower, / Which the same Nye had dealt unto me." At this

clear evidence of cheating Bill exchanges glances with James and

attacks the treacherous Chinaman. When the brawl is over the

floor is littered with cards Ah Sin had been hiding, and an

additional "twenty-four packs" are found in his long sleeves.

Harte intended for the poem to suggest that Chinese laborers

were smart enough to beat Americans at their own corrupt

games—he wrote later that Ah Sin "did as the Caucasian did

in all respects, and, being more patient and frugal, did it a

little better"—but he greatly underestimated the malice and

stupidity of his audience. He was dismayed when many American

readers drew the dim-witted conclusion that what makes the

heathen Chinee "peculiar" is his treacherous dishonesty.

Interpretations aside, the poem was wildly popular. It inspired

several anti-Chinese songs on the west coast, and Harte co-wrote

with Mark Twain a playscript titled

Ah Sin, which was

performed for several months in 1877.

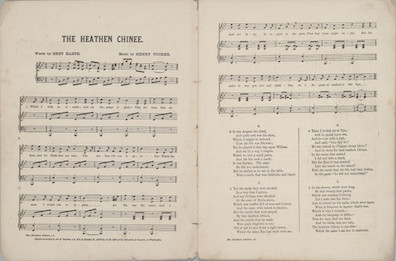

In

Yellowface: Creating the Chinese in American Popular

Music and Performance, 1850s-1920s (2005), Krystyn Moon

writes that "three composers used Harte's

Heathen Chinee

as lyrics. Henry Tucker's

Heathen Chinee (1871) was

quite simple, with only three chords. F. Boote's and Charles

Towner's versions had completely different sonic qualities,

using both musical notation and instrumentation to denote

Chinese difference. Both were written in minor keys, G and F

minor respectively, which gave the lyrics a more ominous and

eerie sound. Boote's

Heathen Chinee (1870) even included

diminished chords and a little syncopation, similar to devices

found in Orientalist art music or blackface minstrelsy. Along

with adding his own words in the form of a chorus to affirm the

moral turpitude of Ah Sin, Towner, in his version of

Heathen

Chinee (1870), included orientalized sounds through the

use of repeated notes in the bass clef and a recommendation that

performers use a gong and a trumpet during the introduction"

(40).

It seems possible that one or more of these song versions

may have been performed on the British music hall stages that gave

Joyce so many of the songs of Ulysses. If any of the

songs did find its way onto such stages, its casual trading in

racial stereotypes would have been right at home in that

raucous low-brow atmosphere. Like the many depictions of black

people drawn from minstrel shows in Ulysses, the image

of a cunning Chinese card-sharp may arouse disgust in 21st

century readers, but circumstances were different in

1904. Bloom cannot be greatly faulted, when he sees an

announcement of a priestly mission to China, for calling up

his one familiar image of that utterly foreign people. And a

man who can assent good-naturedly to the characterization of

his own people as "Ikey" may be

forgiven for perpetuating the name "Chinee."