In Lotus Eaters, as Bloom watches the pious

worshipers in St. Andrew's church and imagines how women may

confess some of their sins to a priest "and do the other thing

all the same on the sly," he thinks of "That fellow that

turned queen's evidence on the invincibles he used to receive

the, Carey was his name, the communion every morning. This

very church. Peter Carey. No, Peter Claver I am thinking

of. Denis Carey. And just imagine that. Wife and

six children at home. And plotting that murder all the time."

In Lestrygonians he is still searching for the first

name: "Like that Peter or Denis or James Carey that blew the

gaff on the invincibles. Member of the corporation

too." The man's name was James Carey, but Bloom remembers his

story quite accurately.

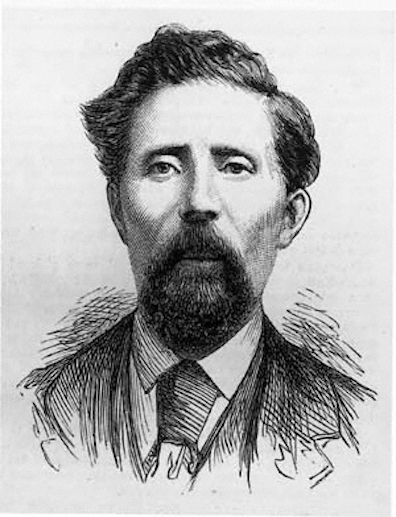

James Carey was the son of a bricklayer who became a builder

and landlord. He lived on Denzille

Street and owned properties also on Denzille Lane,

Hamilton Row, South Cumberland Street, and South Gloucester

Street. By virtue of his success in business he was elected to

the Corporation, and some

people spoke of him as possible Lord Mayor material. But since

1861 he had been a member of the

Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Fenian group that mounted

a violent rebellion in 1867. Carey left the IRB in 1881

and helped to found a new group calling itself the

Invincibles. On 6 May 1882 nine of them wielding long knives

killed the under-secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland,

Thomas Henry Burke, along with Lord Frederick Cavendish, the

Chief Secretary for Ireland, who happened to be with him in

Phoenix Park. The perpetrators were sought for a long time

without success, but in January 1883 Carey and sixteen other

men were arrested. He turned state's evidence, and his

testimony was used to convict and hang five of his fellow

conspirators. The government took him into protective custody

and put him on a ship to South Africa. There, a fellow

bricklayer who became friendly with Carey learned who he was

and shot him dead on board the ship.

Although he cannot remember his given name, Bloom's knowledge

of the man is remarkably full. Carey had a brother named

Peter, likewise committed to violent action. He was elected a

Councillor. He was known for attending services at the

nearby St. Andrew's church

every single day. Igoe quotes a contemporary reporter,

J. B. Hall, who remarked on his "reputation for ostentatious

piety." Thornton describes Bloom's knowledge of Carey's family

situation as "amazingly accurate: in a London Times interview

of February 20, 1883, Mrs. Carey says that they have seven

children, and that the youngest is a baby two months old"

(85).

It is possible that Carey enters Bloom's thoughts because he

has entered the church from the back door on South Cumberland Street.

There, he was only a few steps away from one of Carey’s houses

where the knives from the Phoenix Park murders were found—a

discovery that was widely reported in the newspapers and

caused a sensation. One of Carey's tenants in the house had

seen him using a ladder to make secret trips to the attic and

climbed up to see what was there. He found two long surgical

amputation knives that fit the wounds inflicted in the park.