Joyce modeled Mrs.

Riordan on a Cork woman named Mrs. Elizabeth Conway who may have

been a distant relative of John Joyce and who was governess to

his children from 1888 through the end of 1891. Devoutly

religious, Elizabeth Hearn entered a convent but left before

taking her final vows when her brother died in 1862, leaving her

a large inheritance of £30,000. She married Patrick Conway in

1875, but after living with her for two years he left Ireland

for Buenos Aires with most of her money and did not return. The

experience seems to have permanently embittered Elizabeth.

In

My Brother's Keeper, the anti-Christian Stanislaus

Joyce devotes several pages to a richly detailed portrait of

Mrs. Conway. He calls her the "first educator" of his brother

James, who began the family tradition of calling her

"'Dante'––probably a childish mispronunciation of Auntie" but

one that proved serendipitous. Among other subjects, she taught

James "a good deal of very bigoted Catholicism and bitterly

anti-English patriotism." Stanislaus recalls that Mrs. Conway

"was unlovely and very stout," dressed primly, loved to have the

children bring her "the tissue paper that came wrapped round

parcels," and regularly complained of back pains "which I used

to imitate pretty accurately for the amusement of the nursery."

"She had her bursts of energy, however": when an elderly man

stood up, hat in hand, at a band's playing of

God Save the

Queen, she gave him "a rap on the noddle with her parasol"

(7-11).

For Stanislaus, the intelligence and occasional tenderness of

the governess were far outweighed by her fondness for original

sin, divine judgment, and eternal damnation. "Whatever the

cause," he writes, "she was the most bigoted person I ever had

the misadventure to encounter" (9). The "cause" must have had

much to do with her unhappy marriage, for she also possessed an

unusual degree of vengeful sexual prudery. Jackson and Costello

recount an incident in which she convinced John Joyce's wife to

burn his photographs of his former girlfriends while he was out

of the house. May tried to take the blame, but John knew at once

that the real instigator was "that old bitch upstairs" (159).

The opening section of

A Portrait glances at the

governess's patriotism and her small kindnesses to young

Stephen: "Dante had two brushes in her press. The brush with the

maroon velvet back was for Michael Davitt and the brush with the

green velvet back was for Parnell. Dante gave him a cachou every

time he brought her a piece of tissue paper." (Stephen recalls

these details in

Ithaca.) It then evokes her vicious

religious intolerance. Stephen says that when he grows up he

will marry Eileen Vance, the Protestant girl next door, after

which he is shown hiding "under the table" as his mother says,

"O, Stephen will apologise." Dante: "O, if not, the eagles will

come and pull out his eyes." Mesmerized, the little boy repeats

the refrains "Apologise" and "Pull out his eyes," making of them

a small rhyming poem.

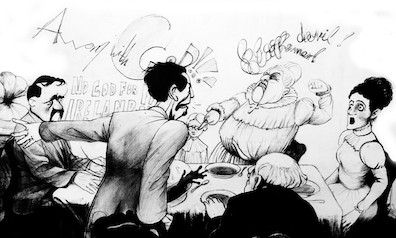

The O'Shea divorce scandal ended Mrs. Riordan's love of Charles

Stewart Parnell, as it did for many puritanical Irish Catholics.

Joyce evoked this watershed in the most powerfully emotional

scene in his fiction, Mrs. Riordan's ferocious argument with Mr.

Dedalus and Mr. Casey at the Christmas dinner of 1891, several

months after Parnell's death. Young Stephen watches the

religious and patriotic halves of his education collide as the

two men abominate the Catholic bishops for betraying Parnell and

the governess spits hatred back at them.

The boy understands that Mr. Casey "was for Ireland and Parnell

and so was his father: and so was Dante too for one night at the

band on the esplanade she had hit a gentleman on the head with

her umbrella because he had taken off his hat when the band

played

God save the Queen at the end." But the church's

hatred of sexual immorality has trumped allegiance to the great

parliamentary leader. At the climax of the argument, fulfilling

the promise of her sobriquet, Dante bellows, "God and morality

and religion come first.... God and religion before

everything!... God and religion before the world!" "Very well

then," Mr. Casey replies, "if it comes to that, no God for

Ireland!... We have had too much God in Ireland. Away with God!"

The governess screams, "Blasphemer! Devil!... Devil out of hell!

We won! We crushed him to death! Fiend!"

Ulysses sounds only faint echoes of this vivid

personality.

Ithaca notes that after leaving the Dedalus

household at the end of 1891, and before dying in 1896, Mrs.

Riordan lived "during the years 1892, 1893 and 1894 in the

City Arms Hotel owned by

Elizabeth O’Dowd of 54 Prussia street where, during parts of the

years 1893 and 1894, she had been a constant informant of Bloom

who resided also in the same hotel." Bloom was kind to the old

woman: "He had sometimes propelled her on warm summer evenings,

an infirm widow of independent, if limited, means, in her

convalescent bathchair" to the North Circular Road, where she

would gaze on its traffic through his binoculars. And

Hades

reveals that when she lay dying in Our Lady's Hospice in the

Mater, he visited her there.

Molly thinks that these "corporal works of mercy" manifested an

ulterior motive. Like the Dedalus children hoping to receive

rewards for bringing tissue papers to the governess, Bloom

"thought he had a great leg of" the old woman and would inherit

something at her death, but "she never left us a farthing all

for masses for herself and her soul greatest miser ever." The

narrator of

Cyclops too remembers this episode: "Time

they were stopping up in the City Arms pisser Burke told me

there was an old one there with a cracked loodheramaun of a

nephew and

Bloom trying to get the soft side of her doing

the mollycoddle playing bézique to come in for a bit of the

wampum in her will and not eating meat of a Friday because

the old one was always thumping her craw." One of the

hallucinations in

Circe represents this view that Bloom

was angling for a bequest. When Father Farley accuses Bloom of

being "an episcopalian, an agnostic, an anythingarian seeking to

overthrow our holy faith," one adherent of the Catholic faith

responds warmly: "

MRS RIORDAN: (Tears up her

will.) I’m disappointed in you! You bad man!"

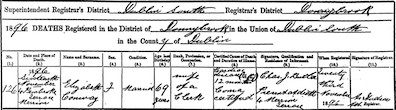

But Bloom knows a sadder part of the story that Molly does not:

Mrs. Riordan's means were indeed "limited," as

Ithaca

notes, her wealth "suppositious." When the real Mrs. Conway died

in November 1896, her assets totaled only £40 6s. 6d. And, in a

supreme irony, administration of the estate was granted to

Patrick Conway, her husband, mysteriously recorded as living at

Dominick Street, Dublin.

Molly hated Mrs. Riordan's constant complaints and her

prudish piety but she respected her learning, and she thinks

that Bloom was not entirely mercenary: "telling me all her

ailments she had too much old chat in her about politics and

earthquakes and the end of the world let us have a bit of fun

first God help the world if all the women were her sort down

on bathingsuits and lownecks of course nobody wanted her to

wear them I suppose she was pious because no man would look at

her twice I hope Ill never be like her a wonder she didnt want

us to cover our faces but she was a welleducated woman

certainly and her gabby talk about Mr Riordan here and Mr

Riordan there I suppose he was glad to get shut of her and her

dog smelling my fur and always edging to get up under my

petticoats especially then still I like that in him polite to

old women like that."