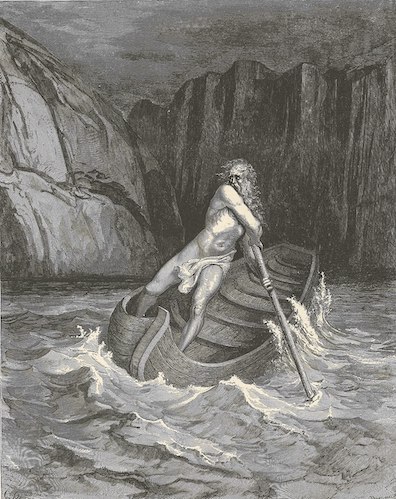

As the funeral carriages pass over the Royal Canal, Bloom watches a

boatman standing on his barge as it drops down into the

draining lock. Since Hades is studded with references

to the underworlds of classical epics, this detail tempts one

to hear an echo of Charon, the boatman who ferries souls

across the river Styx in Virgil's Aeneid and the river

Acheron in Dante's Inferno. The inference is justified

several sentences later as Bloom combines his memory of a

local boatman who recently died with his memory of a poem

about a boatman's deadly water crossing: "James M'Cann's hobby

to row me o'er the ferry."

Gifford notes that James M'Cann "was chairman of the court of

directors of the Grand Canal Company, which maintained a

regular fleet of trade boats on the Grand Canal (to central

and southern Ireland)." Since Bloom is crossing the Royal

Canal, on the north side of Dublin, the geography would seem

to be wrong. But M'Cann, Gifford goes on to observe, died on

12 February 1904. He thus "has already arrived in Hades" and

could very well play the part of Charon, helping Bloom cross

the northern river that separates Dublin from the land of the

dead in Glasnevin. In life such tasks constituted a paying

profession for McCann. Now it seems they are a "hobby."

In a note on JJON, Terence Killeen observes that use

of the word "ferry" to refer not to a boat or its action of

crossing a stream, but to the "place where boats pass over a

river etc. to transport passengers and goods" (in the same way

that a "ford" can be a place as well as an action) is "all but

obsolete now and was probably obscure in 1904." But Bloom, he

suggests, is thinking of a line from a poem written a century

earlier:

A chieftain to the Highlands bound

Cries, "Boatman, do not tarry!

And I'll give thee a silver pound

To row us o'er the ferry."

Lord Ullin's Daughter, published in 1804, was written

by a Scottish poet whose work Bloom seems to know—later in Hades

he tries to recall who wrote Elegy

Written in a Country Churchyard and comes up with

"Wordsworth or Thomas Campbell." Campbell's ballad describes

the plight of Lord Ullin's daughter and the young chieftain

she has run off with as they flee her father's soldiers. The

ferryman agrees to save the bridegroom from the sword, but the

"dark and stormy water" threatens no less mortal peril. Lord

Ullin arrives at the shore of the loch in time to watch his

girl drown: "The waters wild went o'er his child, / And he was

left lamenting."

Lord Ullin's Daughter, then, coheres with the possible

echo of Charon in its depiction of a boat ferrying people over

some very dark waters. By changing "row us" to "row

me," Bloom puts himself in the boat, confirming the

impression that he is being ferried to the land of the dead.

It seems odd that his meditation on McCann and Campbell comes

in the middle of about a dozen sentences in which he thinks

about traveling west along the canal to see Milly in

Mullingar. But these sentences are preceded and followed, at

the beginning and end of the paragraph, by long gazes at the

boatman, so Bloom has him in view the whole time. Death breaks

in on his happy dreaming.