As the funeral carriage rolls past Westland Row on Great

Brunswick Street, Bloom notices a sudden vigorous action in

the street: "A pointsman's back straightened itself upright

suddenly against a tramway standard by Mr Bloom's window."

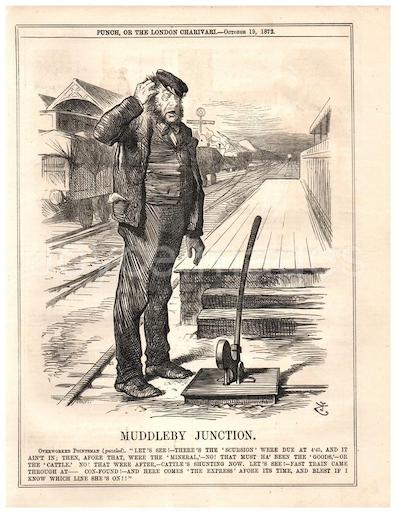

Pointsmen (called switchmen in the U.S.) were railway workers

stationed at track junctions to pull on metal levers that

opened one line or another to oncoming trains. In The

Bloomsday Trams (2009), David Foley observes that "An

example of a standard is now preserved at the national

Transport Museum" (4), which is located inside the main gates

of Howth Castle.

"Points" (sometimes called switch rails, switch points, or

point blades) are pairs of rails, tapered at the ends, that

swing a few inches from side to side to guide train wheels

into either of two sets of fixed rails. They are linked

together to ensure that only one point rests against a fixed

rail at any given time, and often some kind of indicator shows

train drivers which set of tracks is currently open. Today

many of these switches are powered by electric motors or by

pneumatic or hydraulic actuators, but some still require a

human being to shift the points manually, as evidently was the

case in Dublin at the time represented in the novel. In the

1937 photograph displayed here, a pointsman appears to be

manually performing a second function: indicating to a tram

driver which line is open.

Seeing the pointsman's laborious effort, Bloom indulges one

of his fancies about civic improvement: "Couldn't they

invent something automatic so that the wheel itself much

handier? Well but that fellow would lose his job then? Well

but then another fellow would get a job making the new

invention?" The idea that some device might make it

possible for motormen to shift the track's points, eliminating

the need for pointsmen, probably reflects Joyce's awareness of

imminent technological change. The electrification of Dublin's

trams had been completed in 1901, and Foley notes that "Forty

automatic switches were installed at an unspecified date in

1904 and were operated by the driver sending a jolt of current

on to a contact set in the road" (4). These electrical

switches were not activated by a train's "wheel"––the

mechanism that Bloom imagines––but that idea too seems to have

some basis in physical reality. So-called "trailable switches"

allow trains on either of two converging lines (i.e., moving

toward the single set of tracks) to move the points with their

wheels.

Bloom is not simply daydreaming, then. He is applying

technological developments that he has heard of or read about

to the practical business of moving around the city––just as

he will do a bit later later in Hades, when he

suggests that Dublin should have funeral trams as in

Milan. His thoughts about workers losing their jobs and

other kinds of jobs being created is of course a staple of the

modern industrialized economy, often referred to these days as

capitalism's effect of "creative destruction."

Although Joyce does not have Bloom reflect on it, another

kind of economic reality was involved in the job of

"pointsmen." Foley observes that "The tramway company employed

boys" to do this physical labor (4). Slote confirms this

information, quoting from Michael Corcoran's Through

Streets Broad and Narrow: A History of Dublin Trams:

"The pointsmen were frequently boys..., hopefuls for future

employment as motormen or conductors" (70). Corcoran's book

agrees with Foley's also on the installation of electrically

controlled track points: the DUTC experimented with

these new devices in 1903 and installed forty of them in 1904.