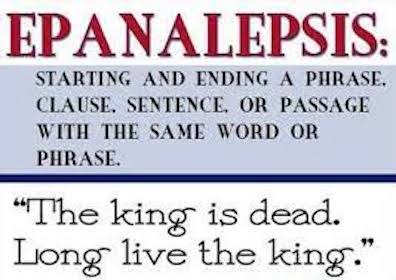

Figure of speech. J. J. O'Molloy ends a sentence

with the word that started it: "— Seems to be, J. J.

O'Molloy said, taking out a cigarettecase in murmuring

meditation, but it is not always as it seems." The rhetorical

term for this device is epanalepsis: using the same

word or words at the beginning and the end of a clause,

sentence, or other substantial block of text.

Best pronounced

EH-puh-nuh-LEP-sis, the Greek word means "resumption" (

epi-

= in addition +

ana- = again, anew +

lepsis =

taking, so "taking up again"). In addition to the rhetorical

uses evoked in the illustrations here, there are many powerful

literary examples of the device: "Once more unto the breach,

dear friends, once more" (Shakespeare,

Henry V); "In a

minute there is time / For decisions and revisions which a

minute will reverse" (T. S. Eliot,

The Love Song of J.

Alfred Prufrock); "They went home and told their wives, /

that never once in all their lives, / had they known a girl like

me, / But... They went home" (Maya Angelou,

They Went Home);

"We know nothing of one another, nothing, Smiley mused. However

closely we live together, at whatever time of day or night sound

the deepest thoughts in one another, we know nothing" (John le

Carré,

Call for the Dead); "Next time there won't be a

next time" (

The Sopranos).

J. J. O'Molloy's sentence may seem to repeat only the word

"seems," but in fact his second clause echoes the first one

quite closely, as can be seen by rephrasing the verb structure

of one clause or the other: "It seems that it is, but it is not

always as it seems"; or, "Seems to be, but seeming is not always

being." Since the sentence involves an ABBA structure (seem, be,

be, seem), it could be classed as a instance of

chiasmus.

Other rhetorical terms are very closely related to

epanalepsis: anaphora (beginning successive

sentences, clauses, or lines with the same word or words),

epistrophe (ending successive sentences, clauses or lines with

the same word or words), and symploce (the combination of

anaphora and epistrophe). Symploce is, if not entirely

synonymous, so nearly so that I am not sure what the

difference consists in. As Seidman observes, it too

could be applied to Molloy's sentence.

The term epanalepsis is usually employed in the way described

above: beginning and ending a phrase in the same way. But it

can also be used more loosely to describe any refrain-like

repetition of a word or phrase after intervening words.

Examples of this device, not cited by Gilbert or Seidman, can

be found in John F. Taylor's speech about Moses:

But, ladies and gentlemen, had the youthful Moses

listened to and accepted that view of life, had he bowed

his head and bowed his will and bowed his spirit before

that arrogant admonition he would never have brought the

chosen people out of their house of bondage, nor followed

the pillar of the cloud by day. He would never have

spoken with the Eternal amid lightnings on Sinai's

mountaintop nor ever have come down with the light

of inspiration shining in his countenance and bearing in his

arms the tables of the law, graven in the language of the

outlaw.