Figure of speech. As Myles Crawford regales his

audience with Ignatius Gallaher's journalistic exploit, he

peppers them with directive questions: "You know how he made

his mark? I'll tell you"; "Remember that time?"; "Whole route,

see?" "Look at here. What did Ignatius Gallaher do? I'll tell

you"; "Have you Weekly Freeman of 17 March? Right.

Have you got that?"; "Have you got that? Right"; "Where do you

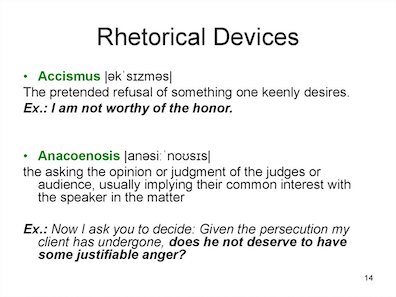

find a pressman like that now, eh?" Rhetoricians call this anacoenosis:

enlisting your listeners in your cause by asking for their

opinions, judgments, or knowledge.

Anacoenosis (AN-uh-sih-NO-sis or AN-uh-ko-uh-NO-sis) comes

from the Greek word anakoinoun = to communicate. It

involves so-called "rhetorical questions": queries that

require a single correct answer or no answer at all. The

tactic is employed regularly by teachers who punctuate their

lectures with one-right-answer questions. Anyone who offers an

answer other than the desired one can be made to feel slow,

misguided, unusual, or disruptive. Like synchoresis,

this device engages an audience while maintaining tight

control of where the argument is going.

Gideon Burton (rhetoric.byu.edu) cites an example from

Isaiah: "And now, O inhabitants of Jerusalem, and men of

Judah, judge, I pray you, betwixt me and my vineyard. What

could I have done more to my vineyard, that I have not done in

it?" (5:3-4). The only correct answer is "Nothing." In his

funeral oration in Julius Caesar, Mark Antony implies

a similar negative answer to a repeated question: "Did this in

Caesar seem ambitious?.... You all did see that on the

Lupercal / I thrice presented him a kingly crown, / Which he

did thrice refuse. Was this ambition?" (3.2.90, 95-97).

This style of instruction suits the newspaper editor in

Joyce's chapter. Crawford is opinionated, short-tempered, and

drunk––not one to waste time on contrary views.