Metaplasm

(MET-uh-PLAZ-um, from Greek

meta- = change +

plassein

= to mold) means changing orthography by subtracting, adding,

transposing,

or substituting letters or syllables. Ancient rhetoricians

identified many different kinds of phonetic subtraction, three

of which appear in one sentence of Dawson's speech.

Apocope (uh-POCK-uh-pee, from Greek

apo- = off,

away from +

koptein = to cut, strike off) refers to

"cutting off" final letters. There are countless examples in

common speech: photo, ad, limo, obit, street cred, the British

pud, the Australian barbie. Even when pronunciation is not

affected, people often like to simplify spellings, changing

"through" to "thru" and "though" to "tho." Dawson's speech uses

an apocope of this sort as it describes a brook babbling on its

way to the sea, "

tho' quarrelling with the stony obstacles."

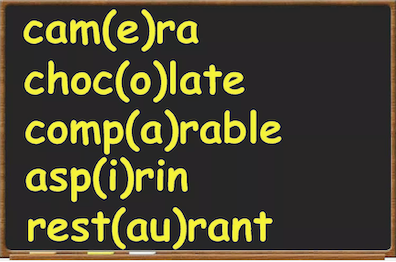

Syncope (SIN-cuh-pee, from

syn- = together,

thoroughly +

koptein) means removing letters or

syllables from the middle of words, as in the nautical terms

"bos'n" for boatswain and "fo'c'sle" for forecastle. This term

is commonly used in linguistics to describe the human tendency

to elide middle syllables, producing sounds like "famly" and

"camra." It is a staple of poetry, or was so in the days when

writers labored to subjugate lexical rhythms to meters like

iambic pentameter. Locating himself in this dying tradition,

Dawson describes the brook luxuriating in "

the shadows

cast o'er its pensive bosom by the overarching leafage."

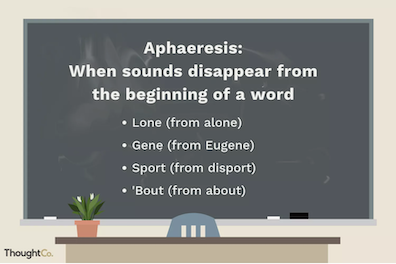

Aphaeresis (uh-FAIR-uh-sis, from

apo- +

hairein

= to take) is the term for "taking away" letters or syllables

from the beginning of words. The removal of an initial syllables

is another useful tool for maintaining meter, and one can hear

Victorian poetic cadences in the phrases "

'mid mossy banks"

and "

'neath the shadows." A bit later in

Aeolus

Ned Lambert reads from the speech a sentence that contains a

slightly different kind of aphaeresis: "

As 'twere, in the

peerless panorama of Ireland's portfolio..."

At first glance this looks similar to "'mid" and "'tween," but

"'twere" is a contraction of two words, and only "it" has been

shortened. Rhetorical theory does provide two terms for

metaplasm involving the contraction of words, though neither of

them seems perfectly relevant here.

Ecthlipsis (ec-THLIP-sis, from Greek

ek- = out +

thlibein

= to rub), a term important mostly for Latin poetry, shortens

the end of one word to join it to the following one in a

metrically desirable way. Gideon Burton (rhetoric.byu.edu)

quotes an example given by the 15th century rhetorician Peter

Mosellanus: "

Multum ille et terris iactatus et alto" can

be shortened to "

Mult'ill'et terris iactatus et alto."

Synaloepha (SIN-uh-LIF-uh, from Greek

syn- = together +

aleiphein = to smear, melt) joins two words by

eliminating a vowel from the end of one or the beginning of the

other, as in these lines from Shakespeare's

Hamlet:

"When yond same star that's westward from the pole / Had made

his course

t'illume that part of heaven." (Apocope is

also operating in "illume.") Neither term quite fits the case of

"'twere," which cuts a vowel from the beginning of the first

word.

If all of the foregoing seems to be getting pretty far down

in the weeds, chasing fine distinctions for small profit, it's

worth remembering that in Finnegans Wake Joyce brought

phonetic subtraction, addition, transposition, and

substitution to a level unimagined in anyone's wildest dreams.

A catalogue of metaplasms in that work would probably fill

hundreds of volumes.