Telephones were not rare in 1904 Dublin. The first ones had

arrived in 1880, and the following quarter century saw a

steady build-out of lines, including trunk lines linking the

city to Drogheda, Dundalk, Belfast, Derry, Mullingar,

Limerick, and Cork. But the device was still far from being an

omnipresent personal convenience. The three phones that Joyce

mentions are all in business offices, and the conversations

that he shows taking place on them consist mainly of

communicating utilitarian data: telephone numbers, prices to

be paid, times of the day, and so forth. Also heard often is

the universal 20th century phone greeting, "Hello." In a

moment of gentle comedy in Aeolus, Bloom's baffled

"Hello?" suggests that many people did not feel entirely

comfortable with this new appliance.

Newspapers would surely have been among the first businesses

to acquire Alexander Graham Bell's revolutionary invention. Aeolus

twice shows a phone ringing in the offices of the Freeman's

Journal and Evening Telegraph. In Wandering

Rocks several other businesses that one might expect to

have telephones––a fruit and flower shop dispatching baskets

all around Dublin, a business promoter arranging concerts and

fights, a hotel doing brisk business on the quays––are shown

to have this amenity. Blazes Boylan's request of the

shopgirl in Thornton's, "May I say a word

to your telephone, missy?," evidently is answered in the

affirmative, because two sections later, as his secretary Miss

Dunne sits in an office a few blocks away, a

telephone rings "rudely by her ear."

— Hello. Yes,

sir. No, sir. Yes, sir. I'll ring them up after five. Only

those two, sir, for Belfast and Liverpool. All right, sir.

Then I can go after six if you're not back. A quarter after.

Yes, sir. Twentyseven and six. I'll tell him. Yes: one, seven,

six.

She scribbled three figures on an

envelope.

— Mr Boylan! Hello! That

gentleman from Sport was in looking for you. Mr

Lenehan, yes. He said he'll be in the Ormond at four. No, sir.

Yes, sir. I'll ring them up after five.

The overheard conversation is a welter of numbers: I'll make

that call "after five," we have only "two" items of business

today, I'll leave work "after six," or "A quarter after" if you

insist, payment in the amount of "Twentyseven" shillings and

"six" pence, i.e. "one" pound "seven" shillings and "six" pence,

and by the way you have an appointment "at four," no I won't

forget to call "after five." An impression of tedious

impersonality prevails, but one may note also the convenience

provided by the telephone. A man who, like Boylan, has access to

one can impose some order on the peripatetic randomness of

moving about Dublin hoping to run into the right people. A

friend wishing to meet him later in the day at a particular

place can simply ring his office and leave a message.

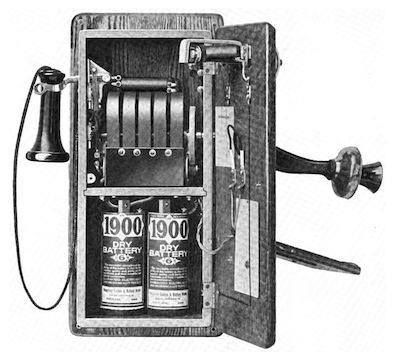

To readers for whom cell phones have conquered space, time, and

human absence, Miss Dunne's brisk chatter sparkles with

recognizably modern efficiency. But telephones have always

brought with them also elements of confusion and frustration,

which in 1904 would have included holding a cone to one's ear,

bending over to shout into another cone, dealing with the

intermediary services of a switchboard operator, and struggling

to ignore the traces of other conversations leaking into the

line. For those who did not regularly use telephones––the vast

majority of the population––the experience must have been

daunting at times. The first time that "The telephone whirred"

in

Aeolus, some rapid-fire business is transacted by an

unknown person: "Twenty eight... No, twenty... Double four...

Yes." On the second occasion, Bloom takes the call and is heard

struggling to converse with some unknown person: "

— Hello?

Evening Telegraph here... Hello?... Who's

there?... Yes... Yes... Yes." His struggles with phone

etiquette, or the deficiencies of the service, or both, may

elicit sympathy as much as laughter.

As Vincent Van Wyk points out in a personal communication, the

awkwardness of Bloom's exchange is serendipitously reflected in

a scene from

Topsy Turvy, Mike Leigh's delightful comedy

about Gilbert and Sullivan and the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company.

The film is set in 1885, when telephones were still quite new,

but it shows people using the phone for business only, as in

Joyce's novel, and transmitting messages in alphanumeric code to

thwart possible eavesdropping by operators. Such practices are

now ancient history, but the clip comically presents other

annoying aspects of the medium that may never entirely go away:

coming up with a phone number, hurling "Hello" into the void,

awkwardly identifying oneself, figuring out ways to begin and

end a conversation with a person whose face one cannot see. Near

the end of the clip, incidentally, readers of

Ulysses

will appreciate the reference to "

Italian hokypoky."

Joyce provides a mocking echo of Bloom's brief phone

conversation in Circe, when editor Myles Crawford

crams "a telephone receiver nozzle to his ear" and

barks, "Hello, seventyseven eightfour. Hello. Freeman’s

Urinal and Weekly Arsewipe here." The

novel also makes one mocking comment on the utility of the

device itself. In Hades the practical-minded Bloom

imagines an utterly impractical way of rescuing buried people

who are not

really dead: "They ought to have some law to pierce the

heart and make sure or an electric clock or a telephone in

the coffin and some kind of a canvas airhole. Flag of

distress." Blackly comic possibilities abound: "Hello? Hello?

Winifred? Um, yes, it's your dearly departed mum here. Yes,

um, about the burial this morning.... You see, it turns out

that I'm not quite dead."