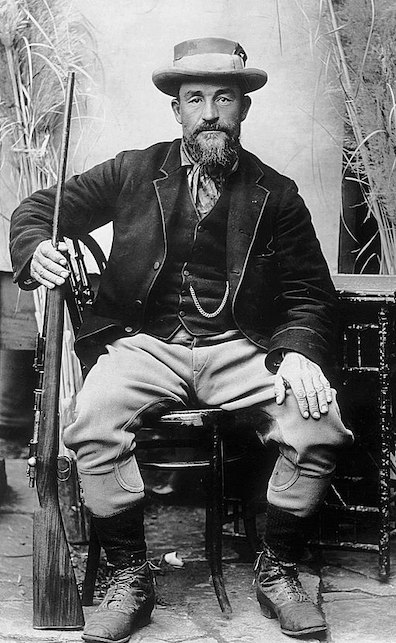

Joe Chamberlain

Joe Chamberlain

In Brief

The Boer War of 1899-1902 aroused intense nationalist

emotions all across Ireland. In December 1899 it prompted the

worst outbreak of political violence that Dublin had seen in a

long time, when a leading British MP named Joseph ("Joe")

Chamberlain came to town to accept an honorary degree from

Trinity College. Protests, counter-protests, and police

crackdowns produced a highly volatile atmosphere.

Read More

In Lestrygonians Bloom watches two squads of constables near the "Trinity railings," site of a confrontation between policemen and protesters of Chamberlain's visit that soon moved west to Dublin Castle, and then north across the Grattan Bridge. Bloom recalls being caught up in the violence that erupted at the far end of this turbulent procession, and the angry shouted protests: "— Up the Boers! / — Three cheers for De Wet! / — We'll hang Joe Chamberlain on a sourapple tree." Christiaan de Wet was a general in the citizen army of the Boers who became its foremost practitioner of guerilla warfare. He returns in Circe, as does the reviled Joe Chamberlain.

Chamberlain had been despised in Ireland since 1886.

Ferociously antagonistic to Gladstone's plans for Home Rule,

he helped defeat that legislation and resigned from the

Liberal Party, causing its government to fall. His new party,

the Liberal Unionists, formed an alliance with the

Conservatives, and when this bloc came to power in 1895 he was

given the office of Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Although he had once been outspokenly anti-imperialist, he

used his new position to pursue an aggressively militaristic

policy toward the Dutch republics in South Africa and

effectively directed the war effort from London. At first the

war went badly for the British: the towns of Ladysmith,

Mafeking, and Kimberly were besieged, and large battles at

Stormberg, Magersfontein, and Colenso were lost in the short

span that came to be known as Black Week. The Irish, who knew

a thing or two about imperial suppression of small republican

nations, greeted the dark news with unbridled joy.

Chamberlain fought opposition to the war with persuasive

speeches in Parliament, with personal attacks on Liberal

politicians whom he cast as all but traitors, and with a trip

to Dublin that many people supposed was designed to show

Ireland's support for the war effort. If this was indeed his

intention, it was a terrible miscalculation. Even before the

start of hostilities Irish nationalists were enlisting to

fight on the side of the Boers in a unit called the Irish

Transvaal Brigade led by Major John MacBride—one of three

Easter Rising leaders executed in 1916 who had fought in South

Africa. After returning from South Africa, where he had worked

in the Transvaal mines from 1896 to 1898, Arthur Griffith worked to form

a political counterpart called the Irish Transvaal Committee,

which was housed in an office on Lower Abbey Street that in

1900 birthed Cumann na nGaedheal, the precursor of Sinn Féin.

Nationalist leaders affiliated with the ITC, including

Griffith, Maud Gonne,

Michael Davitt, the young socialist organizer James Connolly

(also executed in 1916), and the old Fenian leader John O'Leary

planned a pro-Boer protest rally in Beresford Place, not far

from Trinity College and site of another pro-Boer

demonstration on 1 October 1899 that drew 20,000 people. The

authorities planned a massive police response. The resulting

turmoil put paid to any notion that the Irish public largely

supported the British imperial program.

In a book titled Forgotten Protest: Ireland and the

Anglo-Boer War, 2nd ed. (Ulster Historical Foundation,

2003), the Durban-based historian Donal P. McCracken provides

a lively summary of the Chamberlain protest, starting with the

effect that news of British military setbacks had on

Dubliners: "The crowds would thrill with excitement and men,

radiant with delight, would stop strangers in the street and

express their pleasure. Dublin witnessed scenes akin to those

which were to take place in London when Mafeking was

relieved." (Stephen refers in Scylla and Charybdis to

the huge "tide of Mafeking enthusiasm" released in

England when the siege of that town was lifted.) According to

the Freeman's Journal,

"In two brief months, the bravery of the little people has

destroyed the military prestige of the British Empire,

demoralized their troop of enemies, and amazed the world with

the spectacle of what men who prefer death to the destruction

of their nationality can accomplish" (53).

With the news that Chamberlain would be visiting Dublin to

receive an honorary degree on Monday, December 18, plans were

hatched to hold a protest rally in Beresford Place on Sunday,

December 17. On Saturday the authorities in Dublin Castle

issued a proclamation banning the gathering. Griffith threw

his copy into the fireplace. Hundreds of policemen were

deployed on the streets beginning at 11 AM the next day, and a

large force of mounted police armed with sabers was assembled

in the courtyard of the Castle as a reserve force. At about

noon "a brake, or long car," pulled up outside the office of

the Irish Transvaal Committee and at least a dozen leaders

including O'Leary, Griffith, Gonne, and Connolly got in.

Connolly took the reins and "smashed the brake through a

police cordon to get into Beresford Place. The brake was

followed by a mass of people waving Boer flags and cheering

for the Boers" (54-55).

The occupants of the car were briefly arrested, but upon

their release from a nearby police station the brake, followed

by a huge crowd, crossed the O'Connell Bridge, went up

Westmoreland Street, and assembled on College Green outside

the "railings" of Trinity College—the spot where Bloom

thinks in Lestrygonians, "Right here it began."

Police attacked with batons drawn, forcing the crowd to move

west along Dame Street. After speeches and tauntings of the

policemen at points along the way, the crowd came to the end

of the street, where, since it seemed lightly guarded,

Connolly proposed capturing Dublin Castle. Cooler heads

prevailed—fortunately, since hundreds of armed horsemen were

still assembled in the courtyard, unseen. The brake and its

attendant crowd moved north, down Parliament Street toward the

river, followed by the mounted police who had issued from the

Castle after they passed.

When the crowd was across the Grattan Bridge, the officer in

charge ordered his men to charge with sabers drawn. "What

followed was one of the most violent scenes Dublin had

witnessed in a generation. A pitched battle took place . . .

It is said that Arthur Griffith disarmed a mounted policeman.

After the initial shock of the first charge—the police used

the flats of their swords—the crowds retaliated by throwing

whatever they could find. The mounted police were joined by

constables on foot, wielding batons. In the confusion the

brake escaped along Capel Street and turned into Upper Abbey

Street. It is interesting to find that Maud Gonne makes no

mention of this riot in her autobiography" (56).

Back at the office on Lower Abbey Street, "a packed and

jubilant meeting was held," though Davitt was fearful that Joe

Chamberlain might be attacked. McCracken concludes, "The day

was a victory for both sides. From the point of view of the

authorities, they had stamped on a major threat to their

control of the city. It was no accident that Dublin

experienced no more pro-Boer demonstrations of this magnitude.

The police had shown their determination to stand no nonsense.

In the short term, though, the victory was with the Irish

Transvaal Committee. Its prestige now soared in the minds of

many. It was widely, and most likely correctly, believed that

Chamberlain's real motive for visiting Ireland was to

'identify Ireland with the war.' The events of that Sunday

afternoon cast strong doubts on the success of such a mission.

. . . / In fact Chamberlain's visit was a political and

security blunder of the first magnitude . . . no amount

of cheering from the undergraduates of Trinity College could

disguise the psychological victory which the Irish Transvaal

Committee had won" (56-57).

In Lestrygonians Bloom recalls running from the

mounted police, only to see one of them fall from his horse:

"That horsepoliceman the day Joe Chamberlain was given his

degree in Trinity he got a run for his money. My word he did!

His horse's hoofs clattering after us down Abbey street.

Lucky I had the presence of mind to dive into Manning's

or I was souped. He did come a wallop, by George. Must have

cracked his skull on the cobblestones." This detail, confirmed

by contemporary accounts, places Bloom near the climactic

battle that engulfed the quays and Capel Street, at a time

when citizens were desperately fleeing the mayhem. (Manning's

pub was at 41 Upper Abbey Street, on the corner of Liffey

Street.) Had he wandered west from the newspaper offices near

O'Connell Street, or did he join the protest somewhere on its

route from Trinity College to Capel Street?

Wherever his involvement started, it seems that an accidental

encounter with some TCD students brought it about: "I

oughtn't to have got myself swept along with those medicals.

And the Trinity jibs in their mortarboards. Looking for

trouble. Still I got to know young Dixon." Joyce

modeled "young Dixon" on a real-life Joseph F. Dixon who

received a medical degree from TCD in December 1904, so

presumably the other "medicals" Bloom thinks of were also

attending that Protestant ruling-class institution. Slote,

relying on Patridge's dictionary of slang, identifies "jibs"

as first-year undergraduates. It is almost inconceivable that

any Trinity students, much less freshmen, would have been

demonstrating against Chamberlain. There are no contemporary

accounts of them doing so, and it is well known that some did

mount pro-Chamberlain rallies, so the students with whom Bloom

got "swept along" must have been "Looking for trouble" in the

form of violent confrontations with the mostly Catholic

nationalists.

However Bloom may have come to be swept up in the chaos, the

way he praises the great

many Irishmen who fought in the British armed forces

when accosted by two policemen in Circe suggests that

he feels defensive about having held pro-Boer,

anti-Chamberlain views. Bloom tells the constables that his

father-in-law fought in "the heroic defense of Rorke's drift,"

an 1879 action in Zululand, but his sycophancy is met with an

anonymous jeer: "Turncoat! Up the Boers! Who booed Joe

Chamberlain?" In reply, he makes himself a veteran of

the Boer War: "I'm as staunch a Britisher as you are, sir. I

fought with the colours for king and country in the absentminded war under

general Gough in the park and was disabled at Spion Kop and

Bloemfontein, was mentioned in dispatches." Sir Hubert Gough

helped lift the siege of Ladysmith in February 1900. Spion Kop

was the site of a Boer victory in January 1900. Bloemfontein,

the capital of the Orange Free State, fell to the British in

March 1900.

Erected in 1907, the notorious Fusiliers' Arch that guards

the Grafton Street entrance to St. Stephen's Green embodies

the contrary emotions expressed in Bloom's defensive rant to

the constables. It commemorates the courage and sacrifice of

four battalions of Royal Dublin Fusiliers in the Second Boer

War, with inscriptions recording the major battles in which

the Fusiliers took part and the names of the 222 men who died.

Nationalists, however, quickly bestowed a new name on it:

Traitors' Gate, the water entrance through which political

prisoners were long ferried into the Tower of London.

Remarkably, this triumphal arch remains, in McCracken's words,

"one of the few British-erected monuments in Dublin which have

not been blown up" (148).