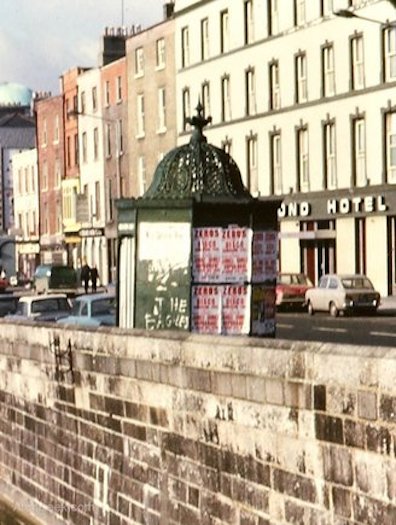

Richard Wall documented this sense of "greenhouse" in An

Anglo-Irish Dialect Glossary for Joyce's Works (1987), A

Dictionary and Glossary for the Irish Literary Revival

(1995), and An Irish Literary Dictionary and Glossary

(2001). In his Dictionary of Hiberno-English (2004),

Terence Dolan quotes from the last of these, which says that

the name referred to "the hexagonal, green, cast-iron public

urinals, which were once part of Dublin's street furniture."

Wall is almost certainly wrong about the hexagonal

shape—photographs show that the structures were octagonal—but

he is almost certainly correct about the color. Present-day

confirmation of that can be found on Horfield Common in

Bristol, England. There, just off Gloucester Road at the end

of a concrete path, stands an ornately decorated,

Victorian-era iron urinal, this one round, that is painted a

bright shade of green. While new paint was no doubt applied

recently, it presumably may have been chosen to match what

came before. A photograph of one of the Dublin urinals on

Ormond Quay, taken in the days of color film, shows that it

too was painted green.

In Penelope, Molly's thoughts about penises lead her

to male exhibitionism and thence to greenhouses: "that

disgusting Cameron highlander behind the meat market or that

other wretch with the red head behind the tree where the

statue of the fish used to be when I was passing pretending he

was pissing standing out for me to see it with his babyclothes

up to one side the Queens own they were a nice lot its well

the Surreys relieved them theyre always trying to show it

to you every time nearly I passed outside the mens

greenhouse near the Harcourt street station just to try

some fellow or other trying to catch my eye as if it was 1 of

the 7 wonders of the world O and the stink of those rotten

places the night coming home with Poldy after the Comerfords

party oranges and lemonade to make you feel nice and watery

I went into 1 of them it was so biting cold I couldnt keep

it when was that 93 the canal was frozen yes it was a

few months after a pity a couple of the Camerons werent there

to see me squatting in the mens place meadero."

("Meadero" is a Spanish word for urinal. The "Camerons," or

"The Queens own," were the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders, an

infantry regiment.)

Molly seems to have experienced some curiosity about what the

greenhouse experience was like. (Does "just to try," at the end

of the first boldfaced passage above, refer to her desire to

peek inside, or is it somehow syntactically connected to men

"trying to catch my eye"?) But her strongest response is to "the

stink of those rotten places," which she associates with men's

"disgusting" desire to display their sexual organs to total

strangers. It would appear that, in the strongly homosocial

environment of 1904 Dublin, men often did not bother to

completely button up before leaving the confines of the

convenience.

Perhaps some connection is implied to the strange moment in

Wandering

Rocks when Stephen's father confronts the viceregal

cavalcade passing by him on Ormond Quay: "

On Ormond quay Mr

Simon Dedalus, steering his way from the greenhouse for the

subsheriff's office, stood still in midstreet and brought his

hat low. His Excellency graciously returned Mr Dedalus'

greeting." The phrase "brought his hat low" could describe

Simon extravagantly doffing his hat, or perhaps making a deep

bow. But would this passionate nationalist ever make such a

gesture of obeisance?

It could perhaps be claimed that Simon salutes the viceroy in a

spirit of sarcastic mockery (your LORDship) or of resigned

cynicism (when in Rome...), but in

James Joyce's Ireland,

David Pierce suggests a different way of understanding the

gesture. He notes that "The plebeian Joyce took delight in

associating the British Establishment with the urinal," notably

in the bizarre detail of

Edward

VII's bucket in

Circe. Simon is coming "from the

greenhouse," a structure which did in fact stand on the river's

edge of Ormond Quay as one of the photographs here shows.

Pierce's comical take is that Simon "has forgotten to button his

trousers" and bends over to remedy the problem, but the Lord

Lieutenant "assumes that one of his subjects is showing respect

and returns the greeting. Across the colonial divide, even basic

signs get misread" (105).

The practice of giving urban men places to relieve their

bladders, at a time when people moved about by foot and indoor

toilets were rare, apparently started in Paris. According to a

page on the Old Dublin Town website (www.olddublintown.com),

they were informally called

pissoirs but the "official

name was

vespasiennes, named after the first century

Roman emperor Vespasianus, who put a tax on urine collected from

public toilets and used for tanning leather." Introduced in 1841

by Claude-Philibert Barthelot, comte de Rambuteau,

the Prefet of the former Départment of the Seine, the

first pissoirs had a simple cylindrical shape and were often

called

colonnes Rambuteau. "In 1877 they were

replaced by multi-compartmented structures, referred to as

vespasiennes.

At the peak of their spread in the 1930s there were 1,230

pissoirs in Paris," but then came a steady decline until in 2006

only one remained.

From Paris the practice spread to Berlin, which held

architectural competitions in 1847, 1865 and 1877 to choose

designs different from the Parisian pissoirs. The Old Dublin

Town site notes that "One of the most successful types was an

octagonal structure with seven stalls, first built in 1879.

Their number increased to 142 by 1920." Something like this

design must have been adopted in Oslo as well, judging by a

Norwegian witticism that Ole Martin Halck has mentioned to me in

a personal communication. One of the circus companies that

regularly visited Oslo after the city constructed a permanent

building in 1890 was called Cirkus Schumann, after its

German/Danish founding family. There was a urinal in Oslo's

central square, Stortorget, that was vaguely round and had a

capacity of seven men ("sju mann"), so this structure too came

to be called the Cirkus Sjumann.

Precise dates are harder to come by for cities in the UK, and

in Dublin the available historical record seems to be almost

entirely photographic. The Old Dublin Town page says that

French-style urinals arrived "prior to the 1932 Eucharistic

Congress, as part of a 'clean up Dublin' campaign," and in The

Encyclopaedia of Dublin Bennett notes that "In 1932,

several ornamental cast-iron pissoirs were imported from

France and erected on the Quays" for that occasion (95). But

Joyce's novel makes clear that they were present much earlier.

Vincent Altman O'Connor suggests that pissoirs may also have

been erected for the same purpose (cleaning up a dirty old

town) before one of the visits of King Edward VII, who came to

Dublin in 1868, 1885, and 1903. In Eumaeus Bloom and

Stephen pass by a "men's public urinal" next to the

cabman's shelter at the Custom House. Later in the same

chapter the narrative, which approaches very nearly the

consciousness of the civic-minded Leopold Bloom, notes

with annoyance that the sailor relieves himself in the street

even though "Some person or persons invisible directed him

to the male urinal erected by the cleansing committee all

over the place for the purpose."

Numerous photos document the presence of greenhouses in

Dublin. At least five images of the pissoir on Ormond Quay

survive, including the color photograph displayed here. As the

poster for The Eagles on its river side suggests, this fixture

lasted into the 1970s, when the Dublin Corporation sold it

to a student for £10. It ended up converted into a gazebo in

someone's back yard in Sandymount.