In his Shakespeare talk, which is studded with countless

phrases from the bard's works, and again in Circe,

Stephen uses a term for promiscuity that he has encountered in

Much Ado about Nothing: "light-of-love." In Circe

the phrase also shows up in Bloom's mouth: "No, no worshipful

master, light of love." Here the Shakespearean diction of Much

Ado overlaps curiously with the language of Freemasonry

to produce a sentence that can be read in radically different

ways, painting Bloom either as a morally upstanding and

reasonable man or as a clownish and lewd figure.

The OED traces "light of love" to early appearances

that declare it a cousin of Elizabethan uses of "light" to

mean "sexually inconstant." In Euphues (1579) John

Lyly uses the phrase adjectivally: "Ah wretched wench, canst

thou be so lyght of love, as to chaunge with every

winde?" Thomas Proctor's A Gorgeous Gallery of Gallant

Inventions (1578) makes it a noun: "The fickle are

blamed: their lightilove shamed." Later uses cited in

the OED show that it could also be a name for loose

women themselves, as in John Fletcher's The Chances

(1618): "Sure he has encountered / Some light-o-love

or other." Joyce uses the phrase in this last sense.

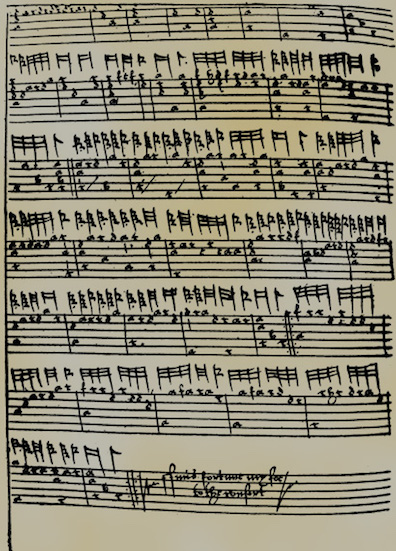

A popular Elizabethan song called "Light of Love," set to a

danceable "turkeylony" tune (the word apparently came from the

tordiglione, an Italian galliard), figures in the

dialogue in which Hero prepares for her wedding and

Beatrice frets over her newfound love for Benedick while

Margaret needles both of them with sexual innuendo:

Hero.

Why, how now? Do you speak in the sick tune?

Beatrice. I am

out of all other tune, methinks.

Margaret. Clap's

into "Light a' love": that goes without a burden. Do you sing

it, and I'll dance it.

Beatrice. Ye

light a' love with your heels! then if your husband have

stables enough, you'll see he shall lack no barns.

Margaret. O

illegitimate construction! I scorn that with my

heels.

(3.4.41-51)

A "burden" was the bass line in a song, and the word

acknowledges the heaviness of Beatrice's love-longing, but it

also echoes "the weight of a man" from several lines earlier.

"Light...with your heels" suggests energetic dancing but also

evokes "light-heeled," another idiom for unchastity. "Barns"

extends the theme of "stables" but also puns on "bairns,"

children. "Illegitimate" refers not only to faulty logic but

also to the fruits of promiscuity. Shakespeare's lush word

play suggests that the song's lyrics must have sent lustful

thoughts racing through Elizabethan minds.

In Scylla and Charybdis Stephen imagines that the

bedroom of every "light-of-love" in London must have

held a copy of Venus and Adonis,

the story of a sexually aggressive woman. In Circe he

thinks of Shakespeare and two other famous men having been dominated by such women:

"We have shrewridden Shakespeare and henpecked Socrates. Even

the allwisest Stagyrite was bitted, bridled and mounted by a light

of love." From the first of these appearances to the

second no real change of meaning or suggestion occurs: the

flighty Anne Hathaway rode roughshod over Shakespeare, and

Socrates and Aristotle experienced similar humiliations.

But later in Circe Bloom uses the phrase in a new and

puzzling way. When a constable threatens to take him to the

police station Bloom performs certain recognizable Masonic

signs and protests, "No, no, worshipful

master, light of love. Mistaken identity." The ruling

officers of Masonic lodges are often addressed as Worshipful

Master, and many Masons have spoken of their order as being a

"light of love" to the world: tolerant, inclusive, highminded,

and charitable. The duplication of meaning here is astounding:

Bloom signals that he is a Mason and hence someone of high

moral character, while at the same time he either confesses to

sexual immorality himself or admits that he has been involved

with a woman of that type.

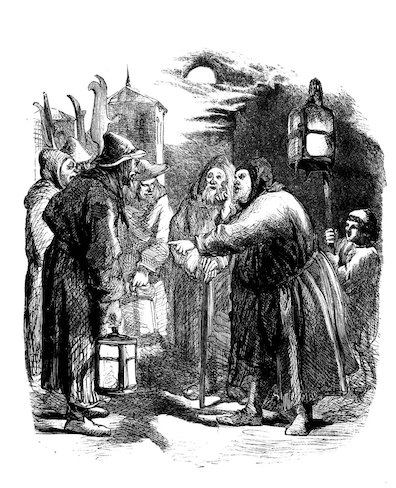

But it is not only "light of love" that proves polysemous. In

a personal communication, Arnie Perlstein has called my

attention to the fact that "worshipful master" may

recall the speech of Dogberry, the bumbling constable in the

subplot of Much Ado. This commoner entrusted with the

job of leading the night watch in Messina stumbles upon Don

John's scheme to ruin the reputation of Hero, but he proves

supremely incapable as an investigator. His clownish idiocy

regularly produces malapropisms and other verbal blunders, and

he is obsequious toward his betters. Worship and Master are

much on his lips, as in these exchanges:

Leonato.

Neighbors, you are tedious.

Dogberry.

It pleases your Worship to say so, but we

are the poor duke’s officers. But truly, for mine

own part, if I were as tedious as a king, I could find

in my heart to bestow it all of your Worship.

Leonato.

All thy tediousness on me, ah?

Dogberry.

Yea, an ’twere a thousand pound more

than ’tis, for I hear as good exclamation on your

Worship as of any man in the city, and though I be

but a poor man, I am glad to hear it.

(3.5.18-27)

Conrade.

I am a gentleman, sir, and my name is

Conrade.

Dogberry.

Write down Master Gentleman Conrade. Masters, do you serve God?

Conrade, Borachio.

Yea, sir, we hope.

Dogberry.

Write down that they hope they serve

God; and write God first, for God defend but God

should go before such villains.

Masters, it is

prov'd already that you are little better than false

knaves, and it will go near to be thought so shortly.

How answer you for yourselves?

Conrade.

Marry, sir, we say we are none.

Dogberry.

A marvelous witty fellow, I assure you,

but I will go about with him.

Come you hither, sirrah; a word in your ear, sir. I say to

you, it is thought you are false knaves.

Borachio. Sir, I say to

you, we are none.

Dogberry. Well, stand aside.

'Fore God they are both in a tale.

(4.2.13-26)

The sycophantish Dogberry acts with spectacular ineptitude as

an officer of the constabulary. The sycophantish Bloom speaks

with spectacular ineptitude to an officer of the constabulary,

urging him to come to the aid of a fellow Mason when there is

almost no chance that the officer is a Mason. No one but Joyce

would discover such a connection in the happenstance

resemblance of two words––much less five––but by joining the

two contexts he creates a brilliant play of meanings. By

saying "No, no, worshipful master, light of love," Bloom

simultaneously claims the moral high ground and gives it away,

declaring himself a virtuous Mason and admitting that he is

only a bumbling oaf, a besotted tool.