In

the

library the other four men chat about the Irish literary scene

while Stephen, feeling excluded, listens in. Someone, probably

John Eglinton, mentions "Miss Mitchell's joke about Moore and

Martyn," that George Moore is Edward Martyn's "wild oats." This

person goes on to remark that "

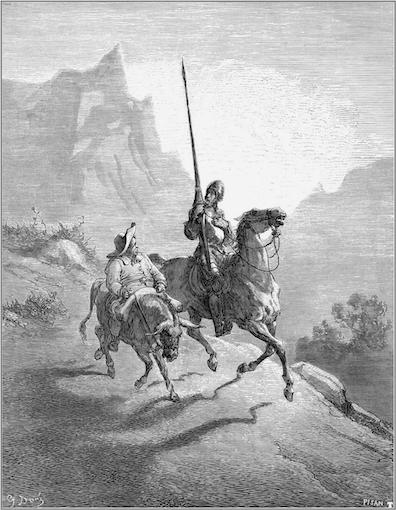

they remind one of Don

Quixote and Sancho Panza. Our national epic has yet to be

written, Dr Sigerson says. Moore is the man for it.

A

knight of the rueful countenance here in Dublin. With a

saffron kilt? O'Neill Russell? O, yes, he must speak the grand

old tongue.

And his Dulcinea? James Stephens is doing

some clever sketches.

We are becoming important, it seems."

This meta-fictive envisioning of a source of great national

pride predicts, of course, the coming of a masterpiece by

someone not named George Moore. So might the references to

Don

Quixote not also apply to

Ulysses?

Cervantes' mocking send-up of medieval knightly romances,

published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, quickly became the "

national

epic" of Spanish culture, and its author quickly assumed

the iconic status that Homer, Dante, and Shakespeare came to

occupy in their cultures. The cultures themselves became "

important"

by virtue of having produced towering works of genius. Like

Dante's poem, Cervantes' prose work offered a model of language

to revere and imitate in a land riven by regional and dialectal

differences. Like Shakespeare's plays it defined national

identity just as nation-states were defining Europe.

Don Quixote has one additional claim to fame: it was, in

the view of many people, the first modern novel. Adventurous

novels like Laurence Sterne's

Tristram Shandy and Mark

Twain's

Huckleberry Finn proclaim their debt to it, and

countless others could never have existed without its

innovations. Mundane, democratic, comical, ironic, skeptical,

subjective, perspectival, dialogic: this work saw where epic

tales would go in an era when ordinary people were grabbing the

spotlight from hereditary elites, prose was displacing verse,

and individual perceptions were starting to seem more real than

universal teachings. It also pioneered a particular narrative

pattern that later novelists would return to again and again.

Two male protagonists who are polar opposites in most obvious

ways, but whose minds somehow mesh, undertake a series of

episodic adventures that highlight both their differences and

their similarities. (One example that rivals Cervantes' stories

for length and readability are the twenty sea novels of Patrick

O'Brian.)

Gifford suggests that Eglinton's reason for comparing Moore and

Martyn to Quixote and Sancho may be primarily physical: "As Don

Quixote is thin so Sancho Panza is fat; George Moore was

slender, Martyn heavy-set. The parallel suggests that the earthy

Martyn tagged around after the ethereal and imaginative Moore."

He acknowledges, though, that Martyn "appears to have been more

of a romantic idealist" than Moore. Neither he nor any other

published annotator appears to have considered that Cervantes'

mismatched duo may also serve as patterns for Joyce's male

leads, who fulfill the archetypes more perfectly. Stephen is

half-starved while Bloom carries around a few too many pounds.

Stephen's head swims with theological abstractions, literary

innovations, dreams of personal vindication, and fantastic

transformations of reality. Bloom thinks of realistic desires,

get-rich-quick schemes, the price of trousers, and his own

shortcomings. But, as

Eumaeus observes, "Though they

didn't see eye to eye in everything, a certain analogy there

somehow was, as if both their minds were travelling, so to

speak, in the one train of thought."

Joyce never again mentions Don Quixote and Sancho Panza in

Ulysses,

but it is interesting to speculate about ways in which their

adventures may inform some of Stephen's and Bloom's. For

instance, tapping his forehead in

Circe, Stephen

declares that "in here it is I must kill the priest and the

king." He is then soundly thrashed by a British soldier. His

grandiose and fantastic dream of killing his country's

oppressors, albeit in a completely peaceful way, contains more

than a whiff of Quixote's futile assaults on imaginary knights

and monsters, which often end with him lying smashed on the

ground. And like Sancho, who is always left to pick up the

pieces, Bloom removes Stephen from the scene of his wild

fantasies, props him up, and escorts him home. The name that

Quixote adopts in Part 1, chapter 19, "

the Knight of the

Rueful Countenance," may have an oblique relevance to

Stephen. Sancho gives him the title because his teeth are so bad

that many of them have fallen out, and Stephen is "

Toothless Kinch, the superman."

Or consider Bloom's dream of a country estate in

Ithaca.

His dogged pragmatism may well owe something to Sancho's, but he

has his own dreams, as does Sancho. Quixote convinces the pig

farmer to become his squire and accompany him on his knightly

quests by promising him that, at some point, he will have his

own island to rule. In Chapters 42-46 of Part II a duke and

duchess trick Sancho into believing that he has found his

ínsula.

He happily sets out learning how to rule his subjects, seeks

advice from the ducal couple and the knight, and does

surprisingly well. Might this episode lurk within Bloom's

never-to-be-realized dream

of acquiring a luxurious

house and grounds and living the life of a country gentleman?

Perhaps not, but his fantasy concludes with the thought that he

will become a "resident magistrate or justice of the peace" and

chart a course of government "between undue clemency and

excessive rigour," dispensing "unbiassed homogeneous

indisputable justice" and "actuated by an innate love of

rectitude."

"And his Dulcinea?" May a reader hope to find her in

Joyce's book? His more quixotic figure, Stephen, has no woman,

but throughout the day he dreams of finding one. In Proteus

he wonders which real woman his dreams might seize on:

"She, she, she. What she? The virgin at Hodges Figgis’ window

on Monday." Cervantes' Dulcinea, similarly, is not a real

woman: Quixote dreams her up out of a village girl who has a

different name, and she never appears in the novel. Sancho, on

the other hand, is married to a quite actual woman named

Teresa Cascajo, and they have a daughter, María Sancha, who

has reached marriageable age just as Milly is doing in Ulysses.

It is hard to say whether Joyce may have paid any attention at

all to these likenesses.

The most abiding law of epics is that they recall and reshape

other epics, reinterpreting the old tradition for new times

and cultures. It seems quite possible that Joyce, like Twain

with his tale of Jim and Huck floating down the Mississippi,

may have conceived his pair of walkers as an updated version

of Cervantes' mounted duo. In their very different ways, both

men embody the mock-heroic spirit of the Spanish novel,

doggedly seeking poetic meaning in a prosaic world.