The Benedictine roots of Mary's Abbey go back to the 9th

century. In the 12th century it became a Cistercian monastery,

and until Henry VIII's abolition of monasteries in 1539 it was

one of the largest and wealthiest in Ireland. The Chapter

House, called "the historic council chamber" in this section

and later "the old chapterhouse," was built in about 1200 as a

place to hold meetings. It survived the fires, pillagings, and

demolitions that destroyed the rest of the abbey––stones from

some structures were used to build the Essex Bridge over the

Liffey (now the Grattan Bridge)––but at some point in time the

grand space was split into two stories. Gifford quotes from D.

A. Chart's The Story of Dublin (1907): "The Chapter

House, which must have been a lofty and splendid room, has

been divided into two stories by the building of a floor half

way up its walls. In the upper chamber, a loft used for

storing sacks, the beautifully groined stone roof remains

intact, looking very incongruous amidst its surroundings"

(276).

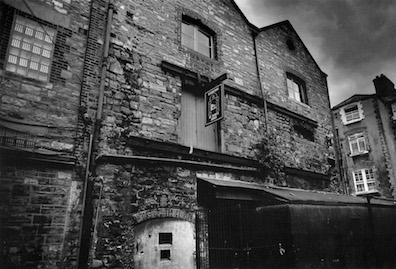

In 1904 a business listed in Thom's as "Alexander

& Co., seed merchants" was using the upper story to store

sacks of grain. This is the scene in which Ned Lambert, an

employee of the business, shows the historic structure to a

visiting clergyman named Hugh Love. The air is so dusky that

Love lights a match to see, and so dusty that Lambert suffers

a fit of violent sneezing after he leaves. Love plans to come

back with a camera the next time he is in Dublin, prompting

Lambert to promise that he will clear grain sacks away from

the windows and to suggest spots from which the scene could be

effectively photographed. Today that task has been admirably

accomplished by Andy Sheridan in the photograph reproduced

here.

Chapter houses were buildings where all the members of a

monastery (or the clergy of a cathedral) could meet to conduct

business. Noblemen, in this case the council that ruled

medieval Dublin, often commandeered them for affairs of state.

Love has come to visit St. Mary's because of his interest in

the aristocrats of his County Kildare, and Ned Lambert tells

him that here "silken Thomas proclaimed himself a rebel in

1534. This is the most historic spot in all Dublin."

Silken Thomas, the son of the 9th Earl of Kildare, renounced

his allegiance to the English crown on the basis of a mistaken report that his

father had been executed by Henry VIII. According to some

historical records he rode out of the mansion of the earls of

Kildare in Thomas Court, the main street of medieval Dublin

("The mansion of the Kildares was in Thomas court," recalls

Love), leading a large force of armed horsemen to Dame's Gate

("He rode down through Dame walk") and thence to St. Mary's

Abbey where he broke into the council of English barons and

proclaimed himself a rebel.

Lambert adds that "The old bank of Ireland was over the

way till the time of the union and the original jews' temple

was here too before they built their synagogue over in

Adelaide road." In the 18th century the Bank of Ireland

was indeed, Gifford notes, "located in what nineteenth-century

guidebooks agree were 'miserable premesis' in St. Mary's

Abbey, a street just north of the Liffey." The dissoution

of the Irish Parliament in 1800 gave them an opportunity

to purchase, in 1803, their grand headquarters on College

Green. The "original jews' temple" was not here. At some time

in the 17th century Dublin's Jewish community founded a

synagogue in Crane Lane, nearby but across the river, and

synagogues were subsequently founded in other places. But in

1836 the congregation purchased a former Presbyterian chapel

at number 12 Mary's Abbey, which had given to the alley its

present name of Meetinghouse Lane. This synagogue closed in

1892 and was replaced by a new, purpose-built synagogue on

Adelaide Road.

Readers struggling to assimilate all this information will

find their attention further diverted by two interpolations.

Partway through section 8 comes an anticipation of the third

sentence of section 16, in which John Howard Parnell is seen

playing chess in the D.B.C: "From a long face a beard and

gaze hung on a chessboard." The interpolation seems to

be prompted by what was happening in the previous sentence,

when Ned Lambert poked around the council chamber looking for

spots to set up a camera: "In the still faint light he moved

about, tapping with his lath the piled seedbags and points of

vantage on the floor." The piled bags blocking movement in

various directions resemble chess pieces positioned around the

board, and "points of vantage" aptly describes the way chess

players think, looking for places from which their pieces can

mount effective attacks. In addition to the chess analogy,

Clive Hart notes a linkage between Charles Stewart Parnell and

the 16th century rebellion of Silken Thomas (Critical

Essays, 206). Desires for independence from the English

crown have been bubbling for five centuries.

A bit later comes a second interpolation, repeating nearly

verbatim a sentence from the end of section 1: "The young

woman with slow care detached from her light skirt a

clinging twig." Here one must look even more carefully

for the implied connections. In the previous paragraph Ned

Lambert was reading to J. J. O'Molloy from the card that the

Protestant minister gave him: "The reverend Hugh C. Love,

Rathcoffey. Present address: Saint Michael's, Sallins. Nice

young chap he is. He's writing a book about the Fitzgeralds he

told me. He's well up in history, faith." Hugh Love is from

Rathcoffey in County Kildare. When Father Conmee was walking

along the road to Malahide in section 1 he "watched a flock of

muttoning clouds over Rathcoffey" and thought of his Clongowes

rectorship in County Kildare. There is more: Hart notes that

"There is an ironic association here with the idea of love,"

because after watching the clouds over Rathcoffey Conmee sees

two irreverend fornicators emerging from the bushes.

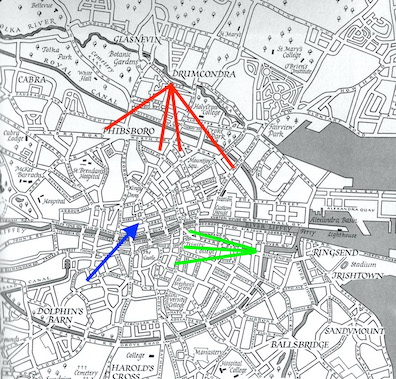

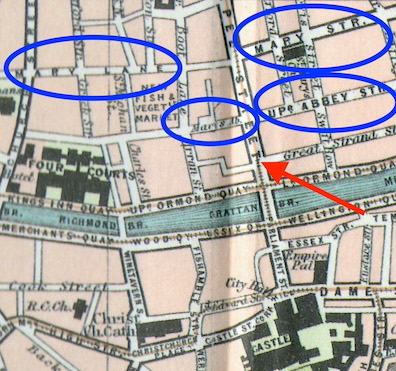

Readers who successfully navigate all these bewildering

twists and turns may yet find themselves briefly stymied when

Lambert follows Love "to the outlet" and comes "forth

slowly into Mary's abbey where draymen were loading floats

with sacks of carob and palmnut meal." Wait... Weren't

the men leaving Mary's Abbey? And why would workmen be

loading grain sacks onto wagons on an upstairs floor? The

seeming absurdities stem from the fact that Mary's Abbey (not

to be confused with Mary Lane, Mary Street, or Abbey Street)

is the name of the street from which Meetinghouse Lane

departs. Alexander & Co. had its offices at 2-5 Mary's

Abbey.

There are no time markers in section 8, but in section 19

Reverend Love sees the viceregal cavalcade passing by "From

Cahill's corner." Gifford's inference that this refers to the

Cahill & Co. printers at 35-36 Strand Street, close to

where Capel Street meets the quays and just north of the

Grattan Bridge, seems clearly preferable to Slote's

identification of Timothy Cahill's pub at 8 Lower Liffey

Street, since the cavalcade crosses the Liffey at Grattan

Bridge and would not be seen further east on the north side of

the river. Since the former Cahill's is only two blocks away

from the Chapter House, it would seem that very little time

has passed since the conversations represented there. Perhaps

their timing can therefore be inferred from the movements of

the cavalcade.