An event of 15 June 1904, reported in newspapers around the

world on the following day, gave Joyce an occasion to include

a representative horror of modern life. The General Slocum,

a triple-decked side-wheel paddle steamboat carrying

German-American women, children, and grandparents from lower

Manhattan to a picnic spot on Long Island Sound, caught fire

on the East River and sank off the Bronx shore. More than

1,000 of the approximately 1,400 people on board drowned,

burned to death, died of smoke inhalation, or were crushed by

huge paddle-blades, in a catastrophe made far worse by

carelessness, ineptitude, and corruption. It was the worst New

York disaster before the attacks on the World Trade Center in

2001, and perhaps only the greater death toll on the Titanic

in 1912 has kept it from continuing its hold on cultural

memory.

In Lotus Eaters Bloom carries around a copy of the Freeman's Journal, which

reported the disaster on the morning of June 16, and in Aeolus

he visits the paper's offices. In Lestrygonians,

before the novel mentions any newspaper accounts, he thinks of

what he has apparently learned from the Freeman: "All

those women and children excursion beanfeast burned and

drowned in New York. Holocaust." Reports of the

disaster surface in Wandering Rocks on newsboards

announcing "a dreadful catastrophe in New York," and in

Eumaeus the "New York disaster" is covered in

the Evening Telegraph.

But the fullest account of the horror comes in Wandering

Rocks when Tom Kernan, pleased with having booked an

order, stops in for a celebratory drink: "I'll just take a

thimbleful of your best gin, Mr Crimmins. A small gin, sir.

Yes, sir. Terrible affair that General

Slocum explosion. Terrible, terrible! A thousand

casualties. And heartrending scenes. Men trampling down

women and children. Most brutal thing. What do they say was

the cause? Spontaneous combustion. Most scandalous

revelation. Not a single lifeboat would float and the

firehose all burst."

"Spontaneous combustion" refers to the fact that the fire may

have started in the ship's Lamp Room, where lamp oil, dirty

rags, straw, or trash on the floor could have been ignited by

a match or cigarette. When a teenage boy reported the fire to

the captain, he was told to shut up and mind his own business.

Some minutes later, the captain realized the truth of the

boy's report, but instead of heading to the nearby Manhattan

shore, where there were stores of oil and lumber, he

accelerated toward an island across the river, steering his

vessel into a headwind that fanned the flames.

The "heartrending scenes" crowd upon one another in

imagination. When the fires grew, sections of deck collapsed,

pitching people into the flames below. Desperate passengers

found that all the lifeboats on the ship were wired and

painted down and could not be lowered into the water. Most of

them could not swim, and the women who tried were weighed down

by the heavy wool clothing of the time. Mothers placed life

preservers on their children and threw them into the water,

only to watch them sink like stones. The life preservers,

which had been hanging in place for 13 years, their canvas

covers rotting, were filled with cheap pulverized cork and

seem to have had iron bars stuck in them to bring them up to

regulation weight. The 36 crewmen had never trained in a fire

drill, and when they tried to put out the fires, the hoses

fell apart in their hands. Rather than assist passengers, many

of them sought their own safety—among them the captain, who

jumped onto a tugboat as soon as the boat settled on the river

bottom, leaving his burning passengers behind.

All of the safety equipment on the boat had passed inspection

a few weeks earlier, but clearly nothing was actually

inspected. The Knickerbocker Steamship Company had a long

history of graft and bribery, uncovered by newspaper

investigations after the disaster, and the General Slocum,

which had suffered numerous groundings and collisions in its

13-year life, had sadly decayed from the showpiece it once

was. Two inspectors were indicted but found not guilty. The

Company received only a small fine. Only the captain, William

Van Shaick, went to jail. Tom Kernan comments on the influence

that big money perennially wields in America: "What I can't

understand is how the inspectors ever allowed a boat like

that... Now, you're talking straight, Mr Crimmins. You know

why? Palm oil. Is that a fact? Without a doubt. Well now,

look at that. And America they say is the land of the free.

I thought we were bad here."

The people who had chartered the General Slocum for

a highly festive outing to Locust Grove, Long Island, hailed

from the working- and middle-class neighborhood of Kleindeutchland

[sic] or Little Germany on the lower east side of Manhattan.

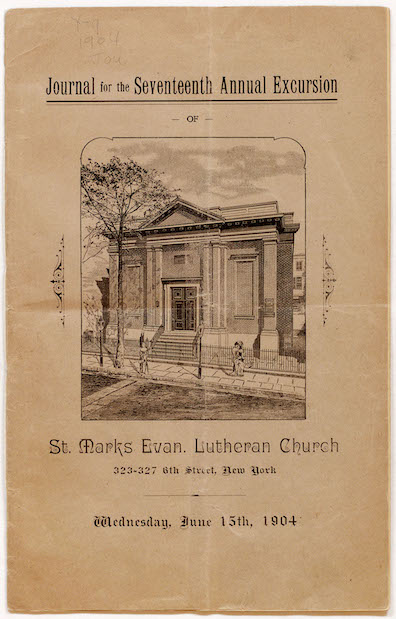

The excursion was organized by the pastor of St. Mark's

Evangelical Lutheran Church, George Haas. It was intended to

celebrate the end of the church school year, and to give

church members a respite from crowded, grimy Manhattan. People

showed up for the long-anticipated trip in their best clothes

and passed up the river in high spirits until the fire broke

out.

The Protestant faith of the victims figures in Wandering

Rocks when Father Conmee, reading about the disaster,

thinks complacently that "In America those things were

continually happening. Unfortunate people to die like that,

unprepared. Still, an act of perfect contrition."

"Perfect contrition" is a safety valve that compassionate

Catholic theologians have dreamed up to save the souls of

people who face death without access to the rite of extreme

unction (normally required): lacking the church's intervention

with God, the sinner's sincere repentance may in certain

exceptional cases be enough. But this kindly indulgence can

hardly be expected to apply to believers who lack the true

faith.