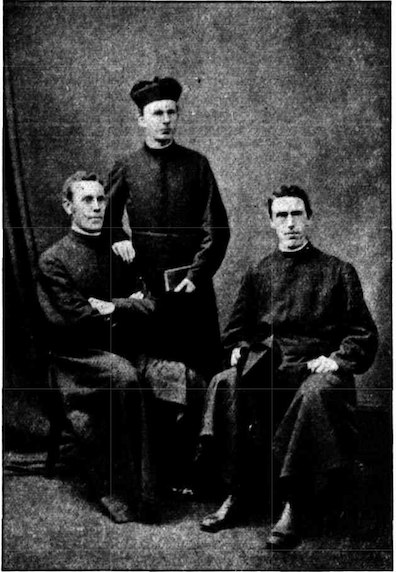

The Congregation of Christian Brothers is a lay teaching

order founded by Waterford merchant Edmund Rice in 1802 to

promote the education of poor Catholic boys excluded by the

18th century penal laws. Although the name suggests a clerical

order of monks or friars, the Christian Brothers are laymen

who, in place of the monk's vows of chastity, poverty, and

obedience, take temporary vows of chastity, poverty, and

"perseverance." Public contributions have always supported

their schools, which keep rates low to make education

affordable. The order has built schools all over Ireland, as

well as many in England, Australia, India, and the Americas.

There are three in Dublin, including the establishments on

Synge Street and Westland Row that Flann O'Brien mocked

uproariously in The Hard Life. The school on North

Richmond Street is named for Daniel

O'Connell, who seems to have played a role in its

founding in 1828. Locally, it has long been called "the

working man's Belvedere."

The O'Connell School figures in Joyce's fictions because his

family lived nearby in the early 1890s and he briefly attended

it. Araby begins, "North Richmond Street, being blind,

was a quiet street except at the hour when the Christian

Brothers' School set the boys free." Wandering Rocks dramatizes

just such a scene: "Father Conmee turned the corner and walked

along the North Circular road. . . . A band of satchelled

schoolboys crossed from Richmond street. All raised untidy

caps. Father Conmee greeted them more than once benignly. Christian

brother boys." Joyce himself was one of those boys for

several months starting in January 1893, after he finished his

studies at Clongowes Wood

College.

John Conmee had been the rector at Clongowes, and he was now

Prefect of Studies at Belvedere. One day in early 1893 John

Joyce crossed paths with Conmee on Mountjoy

Square, told him about the boy who had made a favorable

impression on him at Clongowes, and asked him to admit James

to Belvedere College free of charges, as Belvedere did for

about a quarter of its students. Joyce included the event in A

Portrait:

—I walked bang into him,

said Mr Dedalus for the fourth time, just at the corner of the

square.

—Then, I suppose, said Mrs Dedalus,

he will be able to arrange it. I mean about Belvedere.

—Of course he will, said Mr Dedalus.

Don't I tell you he's provincial of the order now?

—I never liked the idea of sending

him to the christian brothers myself, says Mrs. Dedalus.

—Christian brothers be damned! said

Mr Dedalus. Is it with Paddy Stink and Micky Mud? No, let him

stick to the jesuits in God's name since he began with them.

They'll be of service to him in after years. Those are the

fellows that can get you a position.

—And they're a very rich order,

aren't they, Simon?

—Rather. They live well, I tell you.

You saw their table at Clongowes. Fed up, by God, like

gamecocks.

John Joyce's snobbishness about a Jesuit education, which

must have kept uneasy company with his indigence, communicated

itself to his son, whose fictions do not represent the fact

that he briefly endured the indignity of a Christian Brothers

education. Gordon Bowker's biography notes that he told

Herbert Gorman he had never attended their school (43).

Christian Brothers schools have long been known for harsh

rote learning enforced by harsh discipline. Their noble social

aims notwithstanding, lack of "obedience" to church

authorities or answerability to civic ones encouraged many of

them, especially industrial schools like the one at Artane, to

condone savage beatings of children (despite Rice's

forward-thinking prohibition of corporal punishment), and to

overlook rampant sexual abuse. Their reputation is now fatally

blackened, along with other Irish Catholic institutions like

orphanages and laundries, but the Christian Brothers were a

shaping force in Irish society for two centuries, offering

primary and secondary education to children who might not

otherwise have succeeded economically. Until the scandals

broke they ensured their continuing centrality in 20th century

culture by fostering several generations of nationalist

Catholic leaders.

The pandybat scene in part 1 of A Portrait shows

that even Jesuit schools were not free of cruel and unjust

punishments, and An Encounter suggests that the

public "National Schools," which mostly trained students for

the workplace, may have rivaled the Christian Brothers for

violent abuse. The boy who narrates the story is asked by a

strange man about his friend, "did he get whipped often at

school. I was going to reply indignantly that we were not National School boys to be

whipped, as he called it." The seductive opportunity

that sadists and pederasts discover in holding power over

young schoolboys is vividly evoked in the horrifying sentences

that follow, as the stranger begins "to speak on the subject

of chastising boys."