Almidano Artifoni was born in the city of Bergamo, in

Lombardy, in 1873. He taught at the Berlitz School in Hamburg

in Germany for five years in the 1890s, eventually becoming

its director. In 1900 he moved to Trieste to open the local

Berlitz branch, and a few years later he became important in

the life of the penniless James Joyce, who arrived in Trieste

in October 1904 with his pregnant partner Nora Barnacle.

Artifoni lessened Joyce's hardships by assigning him a

position as an English teacher at the branch office he had

just opened in Pola, southeast of Trieste on the Istrian

coast, and soon afterward in the headquarters of Trieste

itself. In 1907 Artifoni left the direction of the Berlitz

School in the hands of two other teachers. He taught

accounting at the Revoltella Higher School of Commerce and

helped Joyce to obtain the role of English teacher in the same

institute from 1910 to 1913.

Joyce put Artifoni in Stephen Hero as the character

Charles Artifoni, Stephen's Italian teacher at University

College, Dublin: "He chose Italian as his optional subject,

partly from a desire to read Dante seriously, and partly to

escape the crush of French and German lectures. No-one else in

the college studied Italian and every second morning he came

to the college at ten o’clock and went up to Father Artifoni’s

bedroom. Father Artifoni was an intelligent little moro,

who came from Bergamo, a town in Lombardy. He had clean lively

eyes and a thick full mouth." The physical details seem to

have been inspired by Artifoni, but some of the personal

qualities that Joyce assigned to the character, as well as his

given name of Charles, came from his actual teacher at

UCD—another sympathetic Italian man, this one Sicilian, named

Charles Ghezzi. When Joyce reshaped his cumbrous early

novel into A Portrait of the Artist, he let Father

Ghezzi appear under his own name.

The Artifoni of Ulysses may also have been modeled in

part on the Neapolitan maestro Luigi Denza,

professor of voice at the Royal Academy of Music in London and

composer of the well-known song Funiculì funiculà. In

1904 Denza chaired the jury of the prestigious Dublin Feis

Ceoil singing competition. Joyce, who had a beautiful but

untrained tenor voice, had started taking singing lessons from

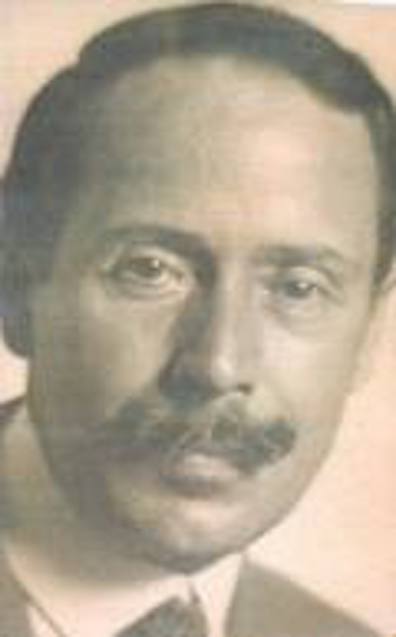

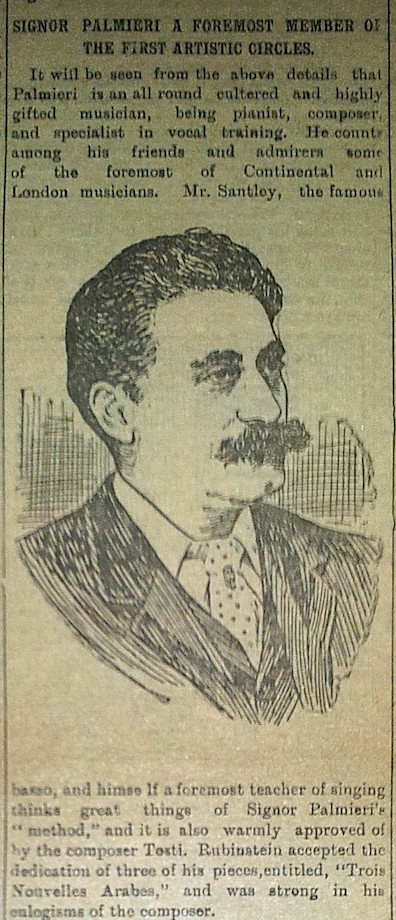

an Italian teacher named Benedetto Palmieri, also born

in Naples, but he ran out of money to pay for the lessons.

John McCormack, the great Irish tenor who had won the gold

medal at the Feis Ceoil in 1903 and who had seen his career

soar as a result, beginning with a year-long scholarship to

study voice in Italy, urged Joyce to enter the competition.

Joyce did, and he sang splendidly, but he grandiosely refused

to do the sight-reading exercise at the end because he had

never learned that skill—even though he knew it was a

requirement of the competition.

According to Ellmann's account of the evening, "The startled

judge had intended to give Joyce the gold medal....The rules

prevented his awarding Joyce anything but honorable mention,

but when the second place winner was disqualified Joyce

received the bronze medal.... Denza in his report urged that

Joyce study seriously, and spoke of him with so much

admiration to Palmieri that the latter, who had made the

mistake of refusing to help McCormack, offered to train Joyce

for three years for nothing in return for a share of his

concert earnings for ten years. But Joyce's ardor for a

singing career had already begun to lapse; the tedious

discipline did not suit him, and to be a second McCormack was

not so attractive as to be a first Joyce" (152).

Ellmann's judgment seems overstated, because when he was

living in Trieste Joyce continued to explore the possibility

of training to become a professional singer. In October 1908

he enrolled at the Trieste Conservatory of Music and became a

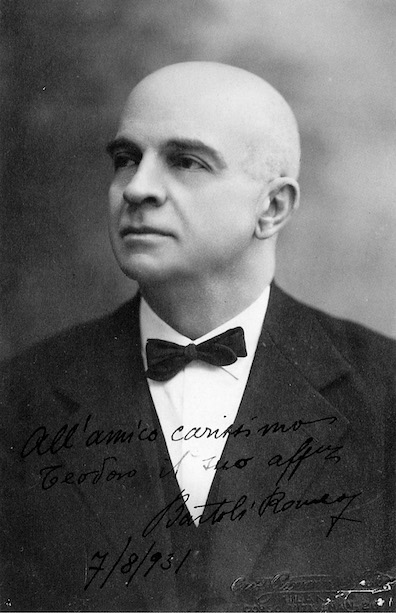

pupil of the maestro Romeo Bartoli, who had

features similar to how Joyce describes Artifoni. Bartoli

confirmed that he was gifted with a rather good voice and

promised him that he would be ready to go on stage within two

or three years. Joyce gave Bartoli some English lessons and it

is possible that the two exchanged professional services in

something like the manner described in Eumaeus and Ithaca,

where Bloom envisions Stephen becoming a professional singer

and Molly acquiring "correct Italian pronunciation,"

the two of them singing "duets in Italian with the accent

perfectly true to nature." In reality, Joyce's singing

career was limited to the performance of a quintet from Wagner's Der

Meistersinger at the Conservatory's end-of-year concert

on 3 July 1909.

Wandering Rocks presents a very warm interaction

between Stephen and Artifoni on College Green as the latter

stands waiting for a tram:

— Ma! Almidano

Artifoni said. [But!—i.e., Who knows!?]

He gazed over

Stephen's shoulder at Goldsmith's knobby poll.

— Anch'io

ho avuto di queste idee, Almidano Artifoni

said, quand'ero giovine come Lei. Eppoi mi sono

convinto che il mondo è una bestia. È peccato. Perchè la

sua voce... sarebbe un cespite di rendita, via. Invece,

Lei si sacrifica. [I too had these ideas when I

was young like you. Then I was convinced that the world is a

beast. It's a shame. Because your voice... it would be a

financial asset, come on! Instead, you are sacrificing

yourself.]

— Sacrifizio

incruento, Stephen said smiling, swaying

his ashplant in slow swingswong from its midpoint, lightly. [A

bloodless sacrifice.]

— Speriamo,

the round mustachioed face said pleasantly. Ma, dia

retta a me. Ci rifletta. [Let's hope so. But

listen to me. Think about it.]

By the stern stone

hand of Grattan, bidding halt, an Inchicore tram unloaded

straggling Highland soldiers of a band.

— Ci rifletteró, Stephen

said, glancing down the solid trouserleg. [I'll think about

it.]

— Ma, sul serio,

eh? Almidano Artifoni said. [But seriously, eh?]

His heavy hand took

Stephen's firmly. Human eyes. They gazed curiously an instant

and turned quickly towards a Dalkey tram.

— Eccolo, Almidano

Artifoni said in friendly haste. Venga a trovarmi e ci

pensi. Addio, caro. [Here it is—i.e., the tram.

Come visit me, and think about it. Goodbye, dear friend.]

— Arrivederla,

maestro, Stephen said, raising his hat when his

hand was freed. E grazie. [Goodbye, Master.

And thanks.]

— Di che? Almidano

Artifoni said. Scusi, eh? Tante belle cose! [For

what? Excuse me, eh?—i.e., for having to run. So many

beautiful things!—i.e., My best wishes!]

Amplified by association with three, four, or possibly even

five other well-meaning and helpful Italian men, Almidano

Artifoni represented for this Irish writer a positive figure

that he wanted to remember in his works and, above all, in his

masterpiece. The "clean lively eyes" of Stephen Hero

become "Human eyes" in Wandering Rocks. Artifoni's touch is welcome to Stephen,

and so is his advice. When he briefly returns in Circe

as a hallucinated figment, he says somewhat aggressively, "Ci

rifletta. Lei rovina tutto" (Think about it.

You're ruining everything). But at the end of Eumaeus

Leopold Bloom presents yet one more layered evocation of

Artifoni, warmly human, physically supportive, and not at all

accusatory. Bloom's efforts to convince Stephen to make money

on the concert stage might seem merely ignorant and venal,

were it not for the personal history that Joyce wove into the

figure of Almidano Artifoni.

[2023] Joyce's dense layering of real people into this one

fictive character makes life tough for his commentators.

Gifford notes that Artifoni gave Joyce a job in Berlitz

schools, but he does not mention Ghezzi, Denza, or Palmieri.

Vivien Igoe gives a biography of Artifoni, noting that he

"never visited Dublin," but likewise ignores other possible

models. Slote and his collaborators say that "Artifoni is

based on Joyce's Italian instructor in Dublin, Father Charles

Ghezzi, S.J." and they note that he used his name in place of

Ghezzi's "in Stephen Hero, but not in A Portrait,"

but they do not mention Denza or Palmieri. Ian Gunn and Clive

Hart, in James Joyce's Dublin, infer that the

fictional Artifoni "is modelled" on Palmieri. They do not

mention Ghezzi or Denza. No one mentions Bartoli.