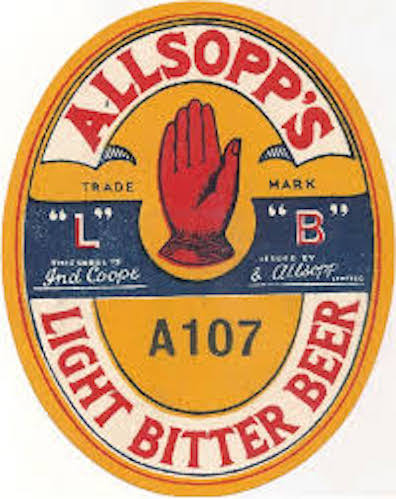

Allsopp's, an English brewing company founded in

Burton-on-Trent in the 18th century (and acquired by Samuel

Allsopp in 1807) is mentioned twice in Joyce's novel. In Lestrygonians

Bloom thinks of Dubliners having a "bottle of Allsop" at

lunch. A much more puzzling reference comes in Cyclops

when Lenehan says that he will have "An imperial yeomanry,"

and John Wyse Nolan translates this to the barman as "a hands

up." Terry confirms the order: "bottle of Allsop. Right, sir."

For anyone familiar with Allsopp's, "hands up" should probably

not be too hard to fathom, as their bottles and ads all

display the image of a upraised red hand. But "imperial

yeomanry" takes obscurity a long step further. It links the

image of raised hands to British soldiers surrendering during

the second Boer War.

In a JJON note, Harald Beck observes that "A raised

red hand had been the Allsopp Brewery’s trademark since 1862.

In 1904 the company reminded the public that their Light

Dinner Ale was also called 'Hand Up' and was thus registered

and protected at the Patent Office." In Ireland the red hand

was additionally associated with the O'Neills of Ulster. A

little earlier in Circe the Citizen has sounded the

fierce clan's "tribal slogan Lamh Dearg Abu"

(Red Hand to Victory) and raised a glass "to the undoing of

his foes, a race of mighty valorous heroes, rulers of the

waves" (i.e., the English). But the two red hands have

different histories. Beck notes that although it "was a common

misconception in Ireland" to hear reference to the O'Neills in

Allsopp's trademark, in fact it was "simply a traditional sign

to signal that the inn in question sold ale of good quality."

The Allsopp's company website cites "an old story that

innkeepers sometimes displayed an open hand to indicate that

their ale was in good condition and ready for sale, and this

is where we believe that our Red Hand derives from."

But the image acquired new resonances from language coming

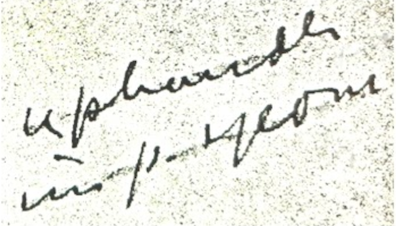

out of the Boer War. One of these terms was "uphander." Beck

notes (with thanks to four industrious colleagues) that

Joyce's notesheets from the summer of 1919 pair "uphander"

and "imp. yeom." and that an earlier draft of the Cyclops

passage has Alf Bergin ordering an "Uphander...

Imperial yeomanry, Terry." In Londinismen, a

German dictionary of English slang published in a revised

edition in 1903, Hans Baumann observes that "uphander" was

"first used in the South-African war in 1900" as a term for

soldiers who surrender in battle and obey the command, "Hands

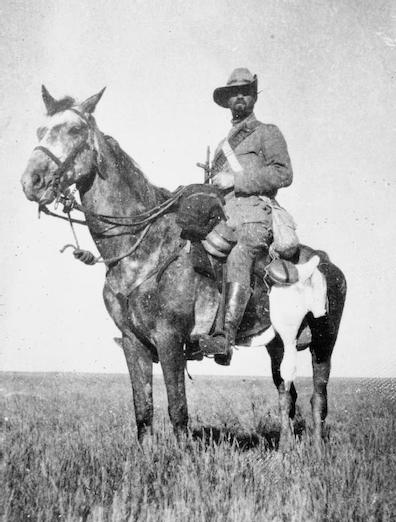

up!” The term could apply to soldiers on either side, but the

men in Barney Kiernan's are thinking of the Imperial Yeomanry

Cavalry, a volunteer unit in the British army which suffered

many defeats in South Africa, especially in the battle of

Lindley in May 1900. Under the headline "Hands Up," a 14 March

1902 article in the Motherwell Times bemoaned the fact

that "An unprecedented and painful feature of the South

African War has been the constant succession of surrenders to

the enemy of unwounded officers and men."

Irishmen sympathetic to the Boers in their overmatched fight

against the imperial war machine apparently seized on this

image of British troops raising their hands in surrender. Late

in Circe, when a "bawd" proclaims that "The red's as

good as the green. And better. Up the soldiers! Up King

Edward!," a "rough" mockingly replies, "Ay!

Hands up to De Wet." This image, it seems, briefly

became linked in Dubliners' imaginations with the raised hands

on Allsopp's beer bottles. Beck and his collaborators have

turned up an article from the 15 July 1905 Evening

Telegraph about "a court case involving a Dublin

county publican who had sold beer of low quality under

Allsopp’s trade name." The article's headline reads,

"Allsopp's 'Hand Up'. A Reminiscence of the Imperial

Yeomanry."

Some Irishmen, many of them from Ulster, enlisted in the

Imperial Yeomanry. Among the 530 British soldiers captured at

Lindley on 27 May 1900 was James Craig, the future Prime

Minister of Northern Ireland. The Ulster connection may add

still another quirky insight into the evolution of these

strange ways of referring to beer. Beck writes, "The fact that

troops of the 60th (Belfast) Regiment of Yeomanry wore a badge

on their helmets featuring the red hand of Ulster on a white

shield may also have played a role in the coinage, just as the

fact that the directors of Samuel Allsopp and Sons Ltd., sent

600 bottles of their light and dark lager for the use of 500

volunteers to the Cape in January 1900." Irish volunteers in

the imperial war effort would have earned particular scorn

from Irish nationalists like those in the bar.

As it happens, Boers in South Africa were expressing similar

feelings of scorn with a word remarkably similar to "Uphander."

In a personal communication Vincent Van Wyk notes that the

Afrikaans term hensopper (hands-upper) was widely

applied to the National Scouts, Boers who had been recruited

into British military units after surrendering in battle.

Nationalists despised these hensoppers as traitors and

give-uppers, much as Irish nationalists despised the treachery

and ineffectuality of the Imperial Yeomanry. The English term

that Joyce used in an early draft of the Cyclops

passage seems close enough to "handsuppers" to suppose that

English and Irish troops coming back from South Africa may

have carried a linguistic parasite with them.

The head-spinning linguistic connections do not stop there.

Van Wyk notes that a kind of near-rhyme obtains between the

Hands-Up beer that John Wyse Nolan orders and the All-Sopps

that Terry delivers. This is not the kind of thing that would

have escaped Joyce's notice. The strangely intricate

linguistic associations in which he turned his mind

loose to recreate were not products of sheer will; he

regularly found them inscribed in the world around him. Van

Wyk spots another such uncanny coincidence in the historical

record. When Lord Kitchener met with the turncoat National

Scouts, it was in Belfast––"Belfast, South Africa that is!"