In the graveyard, Laertes abominates the priest who is giving

Ophelia truncated burial rites: "I tell thee, churlish priest,

/ A minist'ring angel shall my sister be / When thou

liest howling" (5.1.240-42). Thornton cites only this one

allusion, but the conceit of an angelic woman ministering to

fallen mankind (better than the male minister does) evidently

struck a chord with people in the 19th century, when new

economic realities were fostering sharp distinctions in gender

roles. Gifford seems to be aware of this development, noting

that "Sir Walter Scott uses the phrase in Marmion

(1808), sending it on its way toward cliché":

O Woman! in our hours of ease,

Uncertain, coy, and hard to please,

And variable as the shade

By the light quivering aspen made;

When pain and anguish wring the brow,

A ministering angel thou! (6.30)

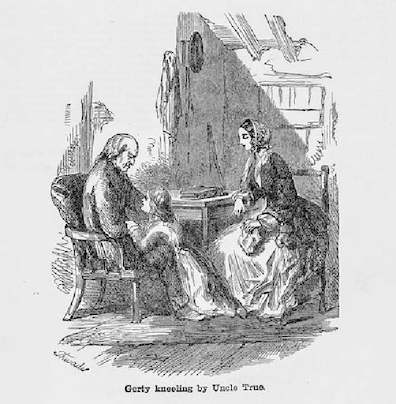

Scott's picture of women ministering to male needs found

followers as the century wore on. Slote notes that Maria Cummins

uses the same Shakespearean phrase as a chapter title in the

best-selling 1854 novel that did so much to inspire the

sentimental prose in

Nausicaa. Chapter 14 of

The

Lamplighter, "

The Ministering Angel," shows Gerty

tenderly assisting Trueman Flint, the kindly old man who adopted

her four or five years previously. True has suffered a

debilitating stroke and he dies at the end of the chapter, after

Gerty warmly reciprocates the loving care he has shown her:

With the simplicity of a child, but a woman's

firmness; with the stature of a child, but a woman's capacity;

the earnestness of a child, but a woman's perseverance—from

morning till night, the faithful little nurse and housekeeper

labours untiringly in the service of her first, her best

friend. Ever at his side, ever attending to his wants, and yet

most wonderfully accomplishing many things which he never sees

her do, she seems, indeed, to the fond old man, what he once

prophesied she would become—God's embodied blessing to his

latter years, cheering his pathway to the grave.

This chapter may have prompted Joyce's phrase "ministering

angel," but he could have encountered many other expressions of

the idea in Victorian writing. One work in particular seems

important to cite as a possible source for the gender

stereotypes in

Nausicaa, as well as its focus on

marriage. English poet and literary critic Coventry Patmore's

The

Angel in the House (1863), a long narrative poem

compiled from four earlier volumes published from 1854 to 1862,

celebrates an ideal of womanhood that Patmore saw embodied in

his wife Emily. Instead of the overt religiosity and relative

gender parity of Cummins's novel, Patmore's poem defines

essential traits, especially purity and submission, that suit

women for the role of wife. It proved hugely popular and

retained its appeal well into the 20th century.

By the time the poem was written, men were commonly understood

to be more aggressive, demanding, and impatient than

women––qualities suited to the industrial and capitalist

workplaces in which they made their way. Women were becoming

housewives, and Patmore's poem helped to define their roles in

life: to create a quiet and comforting domestic sanctuary in

which the man was master, and to pour oil on the troubled waters

of his afflictions, demands, rages, and silences.

The

poem praises its angel's "virtuous spirit," her "woman's

gentleness," her "maiden kindness." One section, titled "The

Wife's Tragedy," describes the selflessness required for such a

role:

Man must be pleased; but him to please

Is woman’s pleasure; down the gulf

Of his condoled necessities

She casts her best, she flings herself.

How often flings for nought, and yokes

Her heart to an icicle or whim,

Whose each impatient word provokes

Another, not from her, but him;

While she, too gentle even to force

His penitence by kind replies,

Waits by, expecting his remorse,

With pardon in her pitying eyes;

And if he once, by shame oppress’d,

A comfortable word confers,

She leans and weeps against his breast,

And seems to think the sin was hers;

And whilst his love has any life,

Or any eye to see her charms,

At any time, she’s still his wife,

Dearly devoted to his arms;

She loves with love that cannot tire;

And when, ah woe, she loves alone,

Through passionate duty love springs higher,

As grass grows taller round a stone.

Patmore never uses the word "ministering" to describe women's

saintly altruism, but Joyce must have been thinking of his poem

or at least of the cult of virtuous housewifery that it

inspired. His Gerty MacDowell is "A fair unsullied soul," a

creature of "gentle ways" who blushes at "unladylike" words, an

angelic creature with "an infinite store of mercy" in her eyes

and "a word of pardon" on her lips. "From everything in the

least indelicate her finebred nature instinctively recoiled."

She knows that men are "so different," capable of becoming a

"devil," "brute," "wretch," or "cad," "the lowest of the low."

She can see maleness coming on even in a young child: "The

temper of him! O, he was a man already was little Tommy

Caffrey." She knows "that a mere man liked that feeling of

hominess," and she looks forward to meeting Mr. Right and

settling down "in a nice snug and cosy little homely house"

where they will have brekky in the morning "and before he went

out to business he would give his dear little wifey a good

hearty hug."

In her 1931 paper "Professions for Women," Virginia Woolf

recounts battling "a certain phantom" that she named "after the

heroine of a famous poem, the Angel in the House." She describes

this soul-draining archetype: "She was intensely sympathetic.

She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She

excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She sacrificed

herself daily. If there was chicken, she took the leg; if there

was a draught she sat in it––in short she was so constituted

that she never had a mind or a wish of her own, but preferred to

sympathize always with the minds and wishes of others. Above

all––I need not say it––she was pure." "Had I not killed her,"

Woolf says, "she would have killed me. She would have plucked

the heart out of my writing." "Killing the Angel in the House

was part of the occupation of a woman writer."

It goes without saying that this act of extermination was

not so urgent a part of the literary occupation for Joyce as

it was for Woolf. But readers of Nausicaa can see that

he added it to his list.