In a 13 July 2015 New York Times review of a

biography of Browne, Jim Holt aptly calls him "a minor writer

with a major style." Browne's prose cannot be mistaken for any

written before or since. It is grand, sonorous, and stately,

but also fresh, quirky, and bursting with ingenious

connections. Holt observes that, "At a time when the

prevailing plain style was growing dull and insipid (John

Locke is an example), it was Browne who showed the way to new

possibilities of Ciceronian splendor. In doing so, he became a

prolific contributor of novel words to the English language.

Among his 784 credited neologisms are 'electricity,'

'hallucination,' 'medical,' 'ferocious,' 'deductive' and

'swaggy.' (Other coinages failed to take: like 'retromingent,'

for urinating backward.)"

Many of Browne's words, whether newly coined or common, come

from Latin or Greek roots. He deftly draws readers on through

brisk colloquial strings of short Saxon words to the

polysyllabic abstractions and analogies on which he wants

their attention to linger. "Break not open the gate of

Destruction, and make no haste or bustle unto Ruin. Post not

heedlessly on unto the non ultra of Folly, or

precipice of Perdition. Let vicious ways have their Tropicks

and Deflexions, and swim in the waters of sin but as in the

Asphaltick Lake, though smeared and defiled, not to sink to

the bottom" (Christian Morals 1.30). "Which conceit is

not only erroneous in the foundation, but injurious unto

Philosophy in the superstruction" (Pseudodoxia Epidemica

2.6). "The world that I regard is my selfe, it is the

Microcosme of mine owne frame, that I cast mine eye on; for

the other, I use it but like my Globe, and turne it round

sometimes for my recreation.... whilst I study to finde how I

am a Microcosme or little world, I finde my selfe something

more than the great. There is surely a peece of Divinity in

us, something that was before the Elements, and owes no homage

unto the Sun. Nature tells me I am the Image of God as well as

Scripture; he that understands not thus much, hath not his

introduction or first lesson, and is yet to begin the Alphabet

of man" (Religio Medici 2.12).

Joyce's parody focuses on such weighty anchor-nouns, and a

few similarly ponderous adjectives and verbs. He exaggerates

the neologisms, the strange locutions, the classical learning,

but the spirit of Browne's original is preserved in his

whimsical imitation. Stephen starts by observing that

canonical texts have little to say about his subject: "This tenebrosity

[darkness, from Latin tenebrae] of the interior

[his mind, the Latin word meaning "further within"], he

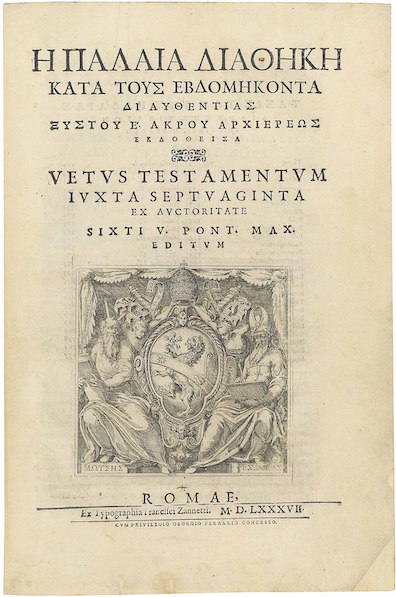

proceeded to say, hath not been illumined by the wit of the septuagint

[an early Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, from the

Greek word for "seventy" because supposedly produced in 72

days by 70 scholars] nor so much as mentioned for the Orient

[the resurrected Christ, from the Latin oriens,

"rising," used in the Vulgate translation of Luke 1:78] from

on high which brake hell's gates visited a darkness that was foraneous

[uncertain meaning––Gifford defines it as "utterly remote,"

but without any attribution; the OED documents a 1656

use referring to a market-place or court, from the Roman forum,

which seems inapplicable]. Assuefaction minorates

atrocities [becoming accustomed to them reduces

their impact] (as Tully [the great Roman orator Marcus

Tullius Cicero] saith of his darling Stoics [the Greek

and Roman philosophers whom Cicero studied]) and Hamlet

his father [i.e., Hamlet's father, in an early modern

form of the possessive] showeth the prince no blister

of combustion [he declines to disclose the

effects of Purgatorial fire to his

son]."

Then Stephen sketches a schematic of human life in which

darkness becomes representative of an underlying truth: "The adiaphane

[Aristotle's Greek word for "non-transparent," pondered

in Proteus] in the noon [middle] of life

is an Egypt's plague [Exodus 7-12] which in the

nights of prenativity and postmortemity

[Latinate pre-birth and post-death] is their most proper ubi

[Latin "where"] and quomodo [Latin "in what manner"].

And as the ends and ultimates of all things

accord in some mean and measure with their inceptions

and originals [the two Latinate pairs articulate

an idea from Aristotle's Physics], that same multiplicit

concordance [manifold correspondence] which leads forth

growth from birth accomplishing by a retrogressive metamorphosis

[development in reverse] that minishing [i.e.,

diminishing] and ablation [Latinate "carrying away" or

"removing"] towards the final [end, from Latin finis]

which is agreeable unto nature so is it with our subsolar

being [life under the sun]."

Finally, Stephen meditates on the biblical life of Moses as a

paradigm of the symmetry of birth and death: "The aged

sisters [the three Fates of Greek mythology, and the midwives

on Sandymount Strand] draw us into life: we wail, batten,

sport, clip, clasp, sunder, dwindle, die: over us dead they

bend. First, saved from water of old Nile,

among bulrushes [sedges, perhaps papyrus stalks, made

into a small boat in Exodus 2:3] a bed of fasciated

[bound together, from Latin fascia, "band"] wattles

[poles woven together with twigs or reeds]: at last the cavity

[hole, from Latin cavitas, "hollowness"] of a

mountain, an occulted [Latin occultus,

"concealed"] sepulchre [Latin sepulcrum, burial

vault] amid the conclamation [Latinate coinage, "great

shouting together"] of the hillcat [perhaps a cougar,

a.k.a. puma or "catamount"] and the ossifrage [bearded

vulture, or lammergeier]. And as no man knows the ubicity

[location, from ubi above] of his tumulus

[Latin for burial mound] nor to what processes we shall

thereby be ushered nor whether to Tophet [the Hebrew

"place of burning" corpses and sacrificing infants, read

typologically by Christians as an image of Hell] or to Edenville

[Stephen's coinage for the earthly paradise

in Proteus] in the like way is all hidden when we

would backward see from what region of remoteness the

whatness of our whoness hath fetched his whenceness."

In Nestor Stephen inverts a famous phrase from John's

gospel to explore an anti-Christian metaphysics

inspired by writers like Averroes, Moses Maimonidies, the

pseudo-Dionysus, Henry Vaughan, and William Blake: "and in

my mind's darkness a sloth of the underworld,

reluctant, shy of brightness, shifting her dragon scaly

folds"; "dark men in mien and movement, flashing in

their mocking mirrors the obscure soul of the world, a

darkness shining in brightness which brightness could not

comprehend." In Oxen of the Sun he returns to

"This tenebrosity of the interior" via the style of Browne,

who shares with fellow 17th century writer Vaughan an affinity

for metaphysical conceits. Stephen says that tenebrosity is

not "illumined" or even mentioned in the Bible, despite the

fact that Christ, after his resurrection, descended into the

"darkness" of Hell to rescue the virtuous souls of the Hebrew

scriptures (the so-called "harrowing of hell"). The darkness

of Purgatory, presumably similar, receives no better

illumination in Shakespeare's Hamlet.

After the first two sentences Stephen turns from the ontology

of Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory to the existential psychology

of human beings. In "the noon of life"––the "brightness" of

this world evoked in Nestor––opacity ("The adiaphane")

seems an affliction dreadful as those described in Exodus. But

on either side of life's brightness are "nights." Life is a

passage from darkness to darkness though a brief interval of

light. (In the Ecclesiastical History Bede vividly

articulated this view with an image of a bird flying through

an open window into a lighted room and back out into

darkness.) Nature forms us into complicated, capable beings,

and then, since "the ends and ultimates of all things"

correspond to "their inceptions and originals," it tears us

down, unmaking what it has made. Mythical old women see us

into life and then out of it. As babies they hide us in arks,

and as corpses they put us in places where only wild animals

hunting for meat may find us. None of us can know where we are

going after death, any more than we can know where we came

from before birth.

Half of one sentence has been omitted from this paraphrase,

as it quotes directly from Browne, requires some contextual

framing, and presents interpretive difficulty. As first noted

by Thornton (Robert Janusko adds the observation that Joyce

came across the words in Saintsbury's study of English prose

styles), "Assuefaction minorates" reproduces two of Browne's

strange coinages. Christian Morals warns against

trusting in visual reminders like memento mori icons

to keep one's thoughts focused on human mortality and divine

beneficence: "Forget not how assuefaction unto any thing

minorates the passion from it, how constant Objects

loose their hints.... When Death's Heads on our Hands have no

influence upon our Heads, and fleshless Cadavers abate not the

exorbitances of the Flesh; when Crucifixes upon Men's Hearts

suppress not their bad commotions, and his Image who was

murdered for us with-holds not from Blood and Murder;

Phylacteries prove but formalities" (3.10). Thornton also

quotes a sentence from Cicero's Tusculan Disputations

that may account for Stephen's remark about Tully's "darling

Stoics": "anticipation...of the future mitigates the approach

of evils whose coming one has long foreseen."

Cicero advocates stoically calming perturbation by dwelling

thoughtfully on the everpresent possibility of loss. Browne's

point is no less clear: Christians must labor to maintain vivid

awareness of the emptiness of earthly goods and the abundant

grace of God. Stephen's meaning seems less certain, but it

certainly differs from both Cicero and Browne. He is either

suggesting that familiarity wears away our awareness of

"darkness" (like Stoics cultivating apatheia, we find ways to

convince ourselves that our lives make sense), or, more likely,

that Hamlet's father has gotten so used to the fires of

Purgatory (true "atrocities") that he doesn't think it worth his

while to describe that dark place to his son.

Many of Stephen's thoughts appear to have been inspired by

one small section of the Religio Medici ("Religion of

the Doctor") in which Browne reflects on the impossibility of

predicting how long a human being may live. All lives may

contain "sufficient oil" for the biblical seventy years, he

writes, but "in some it gives no light past thirty,"

suggesting that "There is therefore a secret gloom or bottom

of our days." God works darkly within the natural processes of

birth, growth, and death: "There is therefore some other

hand that twines the thread of life than that of nature: we

are not only ignorant in antipathies and occult qualities;

our ends are as obscure as our beginnings; the line of our

days is drawn by night, and the various effects therein by a

pencil that is invisible; wherein, though we confess our

ignorance, I am sure we do not err if we say, it is the hand

of God." Several of Stephen's ideas pick up on ideas in

these sentences: the linking of human "ends" with

"beginnings," the eternal presence of "gloom" or "night"

within the light of life, and the myth of Fates spinning out

and cutting the thread of an individual life.

In addition to the Christian Morals and Religio

Medici, Joyce seems to have paid close attention to Hydriotaphia,

Urn Burial. (The English in the title translates the

Greek.) Prompted by the discovery of some four dozen

Anglo-Saxon funerary urns in Norfolk, this impressive work

surveys the many known ways in which human beings have

disposed of their dead, before concluding in the magnificent

final chapter that all such archaeological and anthropological

knowledge is rendered superfluous by Christian belief in the

soul's salvation.

Janusko observes that one sentence in the work's first

chapter anticipates Stephen's linking of birth ("a bed of

fasciated wattles") and death ("an occulted sepulchre").

Browne does it by associating the shape of the human uterus

with a common type of urn: "the common form with necks was

a proper figure, making our last bed like our first; nor

much unlike the Urnes of our Nativity, while we lay in

the nether part of the Earth, and inward vault of our

Microcosme." Janusko notes too that Joyce took the word

"fasciated" from a different passage in the first chapter

which describes Jesus breaking the "fasciations and bands

of death" in his Resurrection. By taking this word which

Browne applies to death and using it to describe the boat that

saved baby Moses, Joyce links birth and death in his own way,

in "a conceit worthy of Browne himself" (65).

The intertextual connections do not end there. Stephen says

that Moses was buried in an "occulted sepulchre" in the

mountains, reflecting the biblical belief that "no man knoweth

of his sepulchre unto this day" (Deuteronomy 34:6). Gifford

notes that this burial is mentioned in the first chapter of Hydriotaphia.

Two other details, the tumuli in which many ancient

peoples interred important leaders, and the cremation implicit

in "Tophet," also suggest awareness of Browne's subject

matter. But, like Browne, Stephen is more interested in the

life of the soul.

Gifford and Slote hear a reference to still another of

Browne's works, Pseudodoxia Epidemica, two paragraphs

later when Bloom tries to assure Stephen that thunder and

lightning are nothing but "the discharge of fluid from the

thunderhead." Browne's scientific thinking probably does

figure here, but it hardly justifies Slote's opinion that his

prose style lingers for two more paragraphs after the

"tenebrosity" sentences. The writing in these later paragraphs

is utterly dissimilar. Stylistic influence must be sought in

other sources.