As the young men gather in the street at the end of Oxen

and prepare to walk to the pub, they express apprehension

about the weather: "Like ole Billyo. Any brollies or gumboots

in the fambly?" "Brollies" is English slang for umbrellas, and

"gumboots," also an English expression, are rubber galoshes.

"Like ole Billyo," a more obscure phrase, might refer either

to the recent violent thunderstorm or to the need to hurry to

the pub as closing time approaches, but in either case the

meaning must be something like "fast and furious."

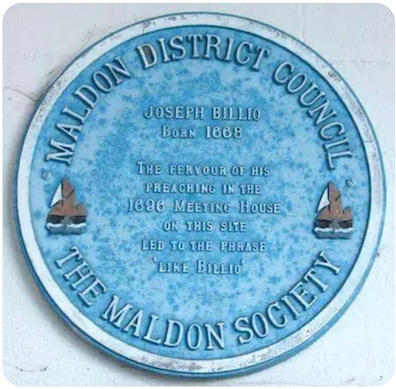

On the Phrase Finder website (www.phrases.org.uk), Gary

Martin discusses "like billy-o" as a still-used "extreme

standard of comparison; for example, 'It rained like

billy-o; we were all soaked through'.” Martin considers

and dismisses a possible inspiration for the phrase in Joseph

Billio, a Puritan minister who preached passionate sermons in

the 1690s at the United Reformed Methodist church in Market

Hill, Maldon, Essex. Although a wall plaque in Maldon claims

that these fire-and-brimstone sermons gave rise to the saying,

Martin concludes that it must have arisen elsewhere: "It

didn’t become common until long after Billio’s death and

disappearance into obscurity (had you heard of him before?)

and doesn’t appear in print for almost 200 years after Billio

died." The first printed record of the phrase, he observes,

can be found in a US newspaper, The Fort Wayne Daily

Gazette, in March 1882: “He lay on his side for about

two hours, roaring like billy-hoo with the pain, as weak as a

mouse.” A closer analogue ("oh," not "hoo") appears in a UK

newspaper, The North-Eastern Daily Gazette, in August

1885: "It’s my umbrella I’ll be lavin’ at home and shure

it’ll rain like billy-oh!"

The use of the phrase to describe intense rainstorms in two

of Martin's examples strongly suggests that Joyce may be using

it in this sense, and if so then his two sentences make up a

coherent unit: "That was some storm! We don't have any

umbrellas or galoshes in the group, do we?" Another

possibility, though, is that someone in the group is saying

that they should proceed with all haste to Burke's pub. Declan

Kiberd notes that the phrase is "Dublin slang for 'very

fast'." Slote, Mamigonian, and Turner agree, citing Eric

Partridge to the effect that "like Billy-ho" means "with great

vigour or speed."

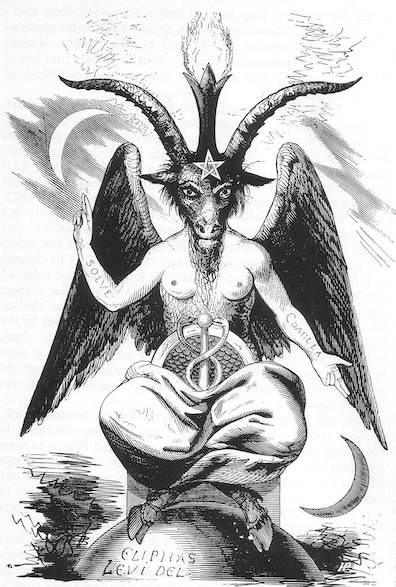

On the same authority they note that "Billy-o" could

refer to the Devil, drawing the inference that "Someone gives

the order to move like the Devil." The name Billy apparently

came to be applied to the devil in the middle of the 19th

century because goats started being called billy-goats in this

time and Satan was sometimes represented with a goat's head or

body in the same era. Joyce's insertion of the epithet "ole"

perhaps supports this reading: Old Billy, Old Nick, the Old

Serpent of Revelation 12:9.

Whether or not Satan is involved, taking the phrase to mean

"very fast" raises further questions, and other posters on the

Phrase Finder website have addressed them. On 8 October 2004 a

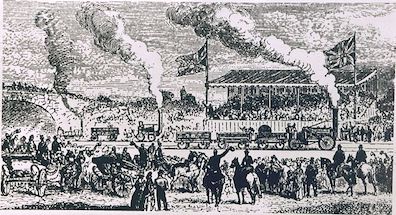

writer identified only as Shae observed that "Billyo entered

the English language in the late 19th century after the

Rainhill steam locomotive trials between Liverpool and

Manchester. These had gripped the public's imagination.

Engineer George Stephenson's Puffing Billy gave rise to the

expressions 'running (or puffing) like Billy-o'. The

Puffing Billy type of 'infernal combustion engine', belching

steam, smoke and fire, must have appeared Dante-esque to

spectators in an era of horsepower and hence its association

with hell. So billyo became a general pseudonym for things

hellish and useful in genteel or young company, where

something could be said to 'hurt like billyo' or one could

invite someone to 'go to billyo' without corrupting or

offending." James Briggs responded to Shae's post later the

same day, adding that calling Stephenson's engine "Puffing

Billy" may have been suggested by the "billypot"––"a can

or pot used to boil water over an open fire."

The Rainhill Trials, held in October 1829, were designed to

test the theory that steam engines mounted on railway cars

could do a better job of hauling freight along rails recently

laid between Liverpool and Manchester than stationary steam

engines pulling cars by cables. The men who had proposed that

theory, George and Robert Stephenson, entered a locomotive

called the Rocket in the contest and it alone completed the

weeklong trials. Robert later remarked that "the trials at

Rainhill seem to have sent people railway mad." If this mania

for locomotive technology did give rise to the expression

"like Billy-o," it is not hard to imagine the image of a

burning, puffing, spouting, furiously fast (25-30 miles per

hour!) machine eventually lending its metaphorical force to

things like rainstorms––or, possibly, in Joyce's case, to a

pack of young men barreling down the street. If Joyce was

aware of the railway context, it forms a fascinating bookend

to the loudly whistling steam fire-engine that he

features near the end of this concluding section of Oxen.

A final point to note about these two sentences is that they

are distinguished by largely English idioms. Slote and his

collaborators, again citing Partridge, observe that "fambly"

is "Cockney pronunciation" for family. Along with the

brollies, the gumboots, and Puffing Billy, they suggest a dip

into distinctively English dialect.