England's great 19th

century art critic (

The Stones of Venice, Modern Painters

I-IV, The Seven Lamps of Architecture) had a single very

unhappy marriage. On his wedding night in 1848 Ruskin found his

wife's body so repulsive that he could not perform as expected.

He does not seem to have suffered from latent homosexuality. He

anticipated his wedding night with the gusto typical of

heterosexual males, writing Effie to say that the thought of

seeing her naked prompted unspeakable urges: "That little

undress bit! Ah—my sweet Lady—What naughty thoughts had I…"

Something about Effie's actual body, though, strangled his

visual fancies in their crib. During annulment proceedings six

years later he said, "It may be thought strange that I could

abstain from a woman who to most people was so attractive. But

though her face was beautiful, her person was not formed to

excite passion. On the contrary, there were certain

circumstances in her person which completely checked it."

The precise "circumstances" that chilled Ruskin's ardor may

never be known, but clearly they had to do with how Effie's

"person," i.e. her body, was "formed." She wrote to her father

that John had pled "various reasons" for not wanting to have sex

with her, but that he "finally this last year told me his true

reason," that "he had imagined women were quite different to

what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his

Wife was because he was disgusted with my person the first

evening 10th April." What unimagined feature of women's bodies

did Ruskin behold for the first time that night? Starting with

Mary Lutyens, an early Ruskin biographer, most people have

assumed it was pubic hair, though alternative explanations have

been advanced. (Menstruation is only barely plausible: most

young men know that women bleed. Disfiguring skin disease seems

still less likely: that affliction would not be common to all

"women." Unattractive odor could explain such a strong reaction,

but it does not square with Effie's mention of "what he saw.")

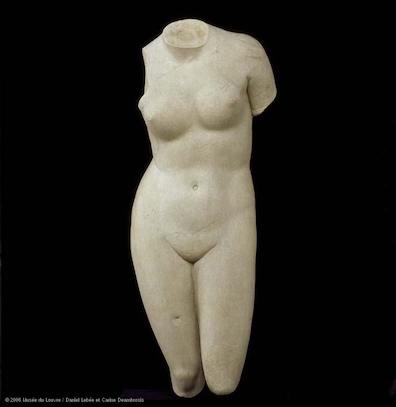

The usual view, that Ruskin thought women have no hair between

their legs, can cite for a cause the fact that he was accustomed

to gazing on classical statues. (In addition to the originals he

no doubt viewed in Italian and French museums, countless

Victorian rooms were decorated with cheap reproductions.) The

syllogistic chain of ideas thus attributed to Ruskin—

classical statues depict ideal female

beauty; those statues have no pubic hair; ergo, beautiful

women lack pubic hair—accounts well for Bloom's thoughts. But if

Bloom wishes to transcend the messiness of genital hair he has

not let it stop him as it stopped Ruskin. And he ultimately

rejects the idealizing impulse in

Circe, attacking the

supposedly suprasexual Nymph as merely presexual: "If there were

only ethereal where would you all be, postulants and novices?

Shy but willing like an ass pissing." The stage directions too

attack her impersonation of purity: "Sacrilege! To attempt my

virtue!

(A large moist stain appears on her robe.) Sully

my innocence! You are not fit to touch the garment of a pure

woman."

The aestheticizing impulse that reputedly infected the fantasies

of one famous Victorian has been hilariously reproduced in

another Irish novel, this one set in Ruskin's era. In J. G.

Farrell's

The Siege of Krishnapur (1973), which is about

the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857, two inexperienced young men, Harry

and Fleury, are intrigued with a young woman named Lucy whose

honor has been compromised. Chapter 16 directs the reader's

attention away from any sexual acts that Lucy may have committed

to the worst offense that another young woman, Louise, can

imagine. Louise supposes that Lucy "allowed, perhaps even

encouraged, certain things to be done to her by a man; she had

perhaps allowed her clothes to be fumbled with and

disarranged... she might even perhaps, for all Louise knew, have

been seen naked by him." It distresses Louise "That a man (let

us not call him a gentleman) should have been permitted to view

that sacred collection of bulges, gaps, tufts of hair and

rounded fleshy slopes." Exposing this "delightfully shaped body"

to the gaze of males represents "a betrayal of her sex."

The erotic charge that characterizes Louise's imagination of the

male gaze certainly attaches to Harry and Fleury, but it becomes

clear that their visual images do not include "tufts of hair."

In chapter 22, the young men experience a version of Ruskin's

wedding night when a black cloud of beetles called cockchafers

invades a room where Lucy is entertaining visitors at tea,

landing on everyone in the room but especially Lucy. She leaps

to her feet and furiously beats at the insects, which cling to

her everywhere and crawl into every available opening. In a

frenzy she pulls off all of her clothes, but still more insects

land on her, falling off in clumps as their weight accumulates.

Harry and Fleury, shocked at "the unfortunate turn the tea party

had taken," watch as "an effervescent mass detached itself from

one of her breasts, which was revealed to be the shape of a

plump carp, then from one of her diamond knee-caps, then an

ebony avalanche thundered from her spine down over her buttocks,

then from some other part of her." The

brief exposures give the young

men "a faint, flickering image of Lucy's delightful nakedness,"

and the erotic spectacle is distinctly aesthetic: watching it,

Fleury dreams up the idea of "a series of daguerrotypes which

would give the impression of movement."

Lucy becomes paralyzed with fear. The men hesitate to touch her,

but when she faints they decide to act. Tearing the boards off a

Bible to use as blades, they scrape the black crawling mass from

her backside and then begin on her front. As they expose swaths

of white flesh, they discover that Lucy's body is "remarkably

like the statues of young women they had seen... like, for

instance, the Collector's plaster cast of

Andromeda Exposed

to the Monster, though, of course, without any chains.

Indeed, Fleury felt quite like a sculptor as he worked away and

he thought that it must feel something like this to carve an

object of beauty out of the primeval rock. He became quite

carried away as with dexterous strokes he carved a particularly

exquisite right breast and set to work on the delicate fluting

of the ribs."

But it turns out that statues have not prepared the young men

for what they will find between Lucy's legs. She has hair

there, and "this caused them a bit of surprise at first. It

was not something that had ever occurred to them as possible,

likely, or even desirable." Having scraped at it to no effect,

Harry asks, "D'you think this is supposed to be here?"

Fleury, who "had never seen anything like it on a statue,"

says, "That's odd.... Better leave it, anyway, for the time

being. We can always come back to it later when we've done the

rest."