After the political and religious apotheosis of Bloom in Circe

has tipped decisively over into sexual derision, he sits

in a pillory while "Artane orphans, joining hands, caper

round him. Girls of the Prison Gate Mission, joining hands,

caper round in the opposite direction." The two groups

of social outcasts ridicule him with crude popular rhymes, one

of them an antiromantic parody of Valentine's Day devotions,

the other a pair of lewd acrostics.

The "Prison Gate Mission" was a charitable institution

founded in 1876 to help young female prisoners return to

productive society. Its inmates chant a ditty that seems

innocuous enough at first glance, but these girls are not

genteel. Like Oliver Gogarty's poem on

the return of the troops to Dublin, their lines conceal

a crude message:

If you see Kay

Tell him he may

See you in tea

Tell him from me.

When spoken, the first line sounds out FUCK, the third one

CUNT. Joyce may have coined these obscenities––no

commentator has yet discovered a precedent––but any dirty mind

could do as much. Various t-shirts these days sport the

message "Eff you see Kay."

The other ditty has a history. The "Artane orphans"––boys

at the O'Brien Institute for Destitute Children, the

charitable institution where Father Conmee hopes to place

Paddy Dignam's son as a result of his "walk to

Artane"––chant these catchy words:

You hig, you hog, you dirty dog!

You think the ladies love you!

In a JJON note, John Simpson quotes similar lines

from "a very old, probably Irish, song" ("You pig, you hog,

you dirty dog / Ya think the girls all love ya / Grand as you

think yerself to be / I think myself above ya"), and also from

"the typescript Diary of Josiah Cocking," an English

work in which a woman named Mrs. Reed writes to a W. Reed that

she is soon to be "married to a proper husband" and will no

longer require his services ("You pig, you hog, you dirty dog,

you think that I do love you; I sent you this to let you know

I think myself far above you").

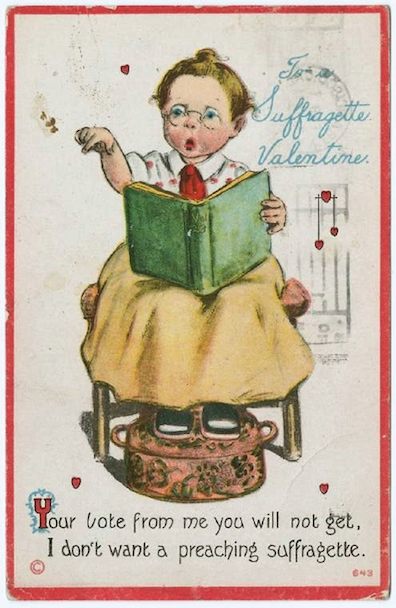

Such lines appear to have been incorporated into some of the

teasing missives that Victorians and Edwardians called

"vinegar valentines" or "comic valentines," commercial

postcards which substituted contempt for loving sentiments.

Simpson notes that a book called Bell's Life in Sydney shows

Betsy Pumpkin writing a letter to her sister on Valentine's

Day, 1849 about how Doodle Pumpkin has received many insulting

valentines, one of which begins, "You pig, you hog, you ugly

dog, / You think the girls all love you; / You ugly beast, not

fit for a feast, / For the New Zealanders to eat you." The

writer of a 1921 article in the Hull Daily Mail

mentions seeing such a valentine in a shop window. If such

verse was common in mock-valentines, Simpson observes, then

"Bloom is perhaps reminded of his lusty wanderings earlier" in

Circe: "You know I had a soft corner for you.

(Gloomily.) ’Twas I sent you that valentine of

the dear gazelle."

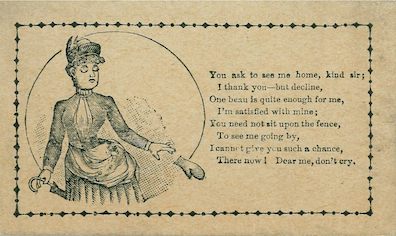

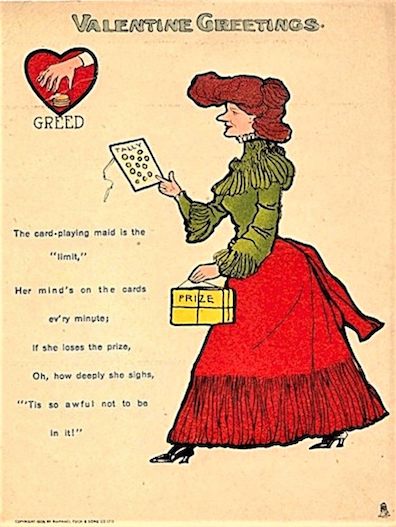

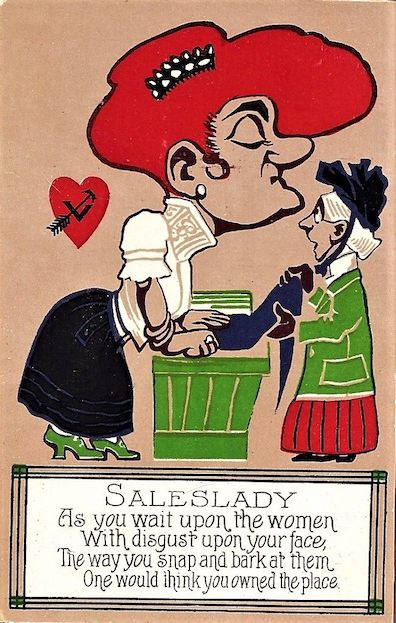

The images displayed here come from Natalie Zarrelli's online

article of 8 February 2017 (updated in 2023) at

www.atlasobscura.com/articles/vinegar-valentines-victorian.

Zarrelli observes that vinegar valentines "were sent

anonymously, so the receiver had to guess who hated him or

her; as if this weren’t bruising enough, the recipient paid

the postage on delivery. In Civil War Humor, Cameron

C. Nickels wrote that vinegar valentines were 'tasteless, even

vulgar', and were sent to 'drunks, shrews, bachelors, old

maids, dandies, flirts, and penny pinchers, and the like'. He

added that in 1847, sales between love-minded valentines and

these sour notes were split at a major New York valentine

publisher. Some vinegar valentines were playful or sarcastic,

and sold as comic valentines to soldiers—but many could really

sting." For Bloom, there can be little doubt that the

intention is to sting.