Joyce told Frank Budgen that this was his favorite chapter, a

preference which says much about its quality but may also

reflect its having stemmed very directly from his educational

training. Catholic catechisms indoctrinate young people in the

tenets of their new faith via a long series of loaded

questions and definitive answers, and Joyce had to memorize

two of them before his tenth birthday. They are dull,

elementary exercises, but in Joyce they whetted an appetite

for more sophisticated question-and-answer discourses like

Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologica (aka Summa

Theologiae) and Summa contra Gentiles,

philosophical works which break down every important aspect of

Catholic teaching into categories, subcategories, and

subsubcategories, state the correct position on a given

subject, consider the objections that can be made to it, and

counter them with detailed replies. Joyce became a devotee. In

Scylla and Charybdis Stephen refers to "Saint

Thomas...whose gorbellied works I enjoy reading in the

original," and later in the chapter Mulligan mocks him for it:

"I called upon the bard Kinch at his summer residence in upper

Mecklenburgh street and found him deep in the study of the Summa

contra Gentiles in the company of two gonorrheal ladies,

Fresh Nelly and Rosalie, the coalquay whore."

Although these Catholic rational habits clearly inform

Joyce's method, Ithaca pointedly rejects the

otherworldly premises of Catholicism in several allusions to

Dante's Divine Comedy, and instead takes a

quasi-scientific approach to very earthly subject matters. It

makes sense, then, that in addition to his religious

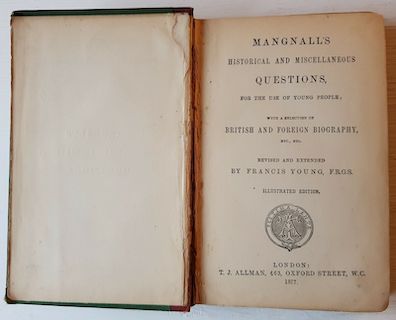

inspirations Joyce had a secular catechism in mind. Citing the

work of two other scholars, A. Walton Litz observes (Critical

Essays, 394) that the chapter is clearly indebted to

Richmal Mangnall's Historical and Miscellaneous Questions,

an encyclopedia-like textbook of history, biography, and

science "for the use of young people." First published in

1798, this durable educational staple went through more than

one hundred editions throughout the course of the 19th

century. In part 1 of A Portrait of the Artist, as

Stephen works up his courage to tell the rector about his

unjust punishment, he thinks, "A thing like that had been done

before by somebody in history, by some great person whose head

was in the books of history. And the rector would declare that

he had been wrongly punished because the senate and the Roman

people always declared that the men who did that had been

wrongly punished. Those were the great men whose names were in

Richmal Magnall’s Questions."

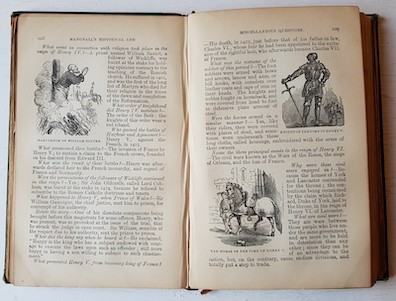

The Questions take children's brief naive queries and

flood them with information. Litz quotes this one:

What are comets?

Luminous and opaque bodies, whose motions

are in different directions, and the orbits they describe very

extensive; they have long translucent tails of light turned

from the sun: the great swiftness of their motion in the

neighbourhood of the sun, is the reason they appear to us for

such a short time: and the great length of time they are in

appearing again is occasioned by the extent and eccentricity

of their orbits or paths in the heavens.

This professorial sentence could almost be mistaken for one

of Joyce's in Ithaca. "There can be no doubt," Litz

remarks, that Mangnall's work "was a primary source for

Joyce's

'mathematico-astronomico-physico-mechanico-geometrico-chemico

sublimation of Bloom and Stephen'. To the modern adult reader

it is filled with unconscious humour and grotesque

distortions, but to the young Joyce it must have shimmered

with the poetic magic of unfamiliar names and mysterious words

(such as gnomon and simony)" (394). Running across such words,

and running to a dictionary to look them up, is one of the

great pleasures of reading Ithaca.

Both the church's theological discourses and Mangnall's

historical and scientific tome must have appealed to Joyce's

love of precise language and orderly rational categories, but

to adopt their stolidly straightforward industriousness would

have been intolerable. He found antidotes to the catechism's

stultifying quality in playful caprices, unpredictable

digressions, wry wit, and outright jokes. Ithaca is a

sham catechism—pseudo-scientific, rationality on laughing gas.

No less than any other late chapter in Ulysses, it is

animated by an archly parodic spirit. Litz floats the

interesting notion that it approaches "self-parody" (390, 395)

by aping the author's own Jesuitical intellectual habits.

There is a kind of escalatory logic to this. Cyclops

mocks patriotic Irish male blather and Nausicaa mocks

women's sentimental fiction. Oxen of the Sun sends up

ten centuries of English literary prose, Circe

explodes drama from the inside, and in Eumaeus the

keys to the car are handed over to someone as lacking in literary

skill as the novel's protagonist. After all this raising

of stakes, why not shoot the moon by mocking the author

himself?

But for all its self-referential hyper-rationality, Ithaca

never abandons the spirit of naive openness that catechisms

seek to foster in children's malleable minds, and it lays out

its story in an reassuringly straightforward way. Narrative

movement is conveyed through five clearly defined scenes.

First Stephen and Bloom walk from the quays to Eccles Street,

trying out a wide range of intellectual topics. Then a second

long conversation—nearly half the chapter—is conducted in the

kitchen as Bloom prepares and serves cocoa. More conversation

occurs after the two men leave the house by the back door and

stand in the garden under the stars. After Stephen leaves, a

fourth section of the chapter follows Bloom as he reenters the

house and spends some time alone in the parlor. Finally Bloom

is in his bedroom, putting away clothes, climbing into bed

with Molly, thinking about her as she sleeps, and engaging in

conversation with her when she wakes up. In his early

typescript drafts of the chapter, Joyce named these five

scenes: "street," "kitchen," "garden," "parlour," "bedroom"

(Litz, 398).

Ithaca delights in little logical puzzles that twist

readers' brains into pretzels, but a greater part of its

energy is devoted to the more straightforward business of

cataloguing things: topics of conversation, sequences of

actions, contents of rooms, contents of bookshelves, contents

of desk drawers, articles of clothing, mechanics of water

delivery, properties of water, astronomical phenomena,

characteristics of penises, places in Ireland, places abroad,

financial assets, credits and debits, daydreams of wealth,

moneymaking schemes, events of the past day, plans for the

future, possible bad ends to life, unsatisfactory conditions

of embodiment, unsatisfactory conditions of marriage, reasons

for divorcing, reasons for remaining married, strategies for

achieving equanimity, stages of sexual attraction, things

never quite understood—and on and on. These lists, some of

them obsessively long, feel as comprehensive and as

exhaustively detailed as Aquinas's analysis of theological

problems, and they create a sense of epic scope not unlike the

catalogues in Homer's Iliad.

But it is the Odyssey that Joyce's artistic

architecture most overtly invokes, and as in all the other

chapters readers must think about how to respond to the

invitation. How little or how much of the epic's violent

climax is echoed in the novel's story of coming home at the

end of a humdrum day? How much or little does Joyce's everyman

protagonist resemble Homer's extraordinary hero? How broadly

or minutely, and how often or rarely, are intertextual

connections insinuated? Joyce drops some very precise

reminders of Homer's episode into his own: Stephen and Bloom

constitute a "duumvirate" as they walk to

the house on Eccles Street, Bloom employs "A

stratagem" to get into it, Bloom thinks of a "preceding

series" of 24 men who came before Blazes Boylan, and he

asks "What retribution, if any" should redress the violation

of his matrimonial bed. But the answer to this

question—"Assassination, never, as two wrongs did not make one

right. Duel by combat, no. Divorce, not now...."—makes clear

that modern Ireland is not archaic Greece, poor Bloom is not

mighty Odysseus, and pacifist Joyce is not bloodsoaked

Homer.

Still, it seems certain that Joyce did not intend only faint

ironic echoes of Homer's rousing climax. Ithaca is

about regaining control—not through acts of savage violence,

as in the Odyssey, but through mental mastery of

life's insufficiencies. Bloom's efforts to achieve

"equanimity" about a crisis in his marriage are as heroic in

their small way as Odysseus's efforts to drive rival males out

of his palace, and the chapter's serenely detached prose

presents many other ways in which he rides out waves of worry,

distrust, insecurity, hostility, jealousy, and sorrow. Turning

on a tap elicits gratitude and wonder for the presence of

water. Failing to have bet on a winning horse brings not

disappointment but calm reflection. A viciously antisemitic

song about broken windows prompts him only to reflect that his

kitchen window remains unbroken. Intellectual frustrations

with Molly end in deep physical satisfaction as he lies

nestled in her backside. Fantastical dreams of sudden wealth

help him get to sleep at night. Visions of a beautifully

furnished house in the suburbs provide a mental landscape of

fulfillment beyond each day's economic striving, just like the

one that drives Odysseus on from island to island, back home

to Ithaca.

If this response to the chapter is on target, then its

strange pairing of epic triumph with schoolboy

instruction—Joyce called it the "ugly ducking" of the novel—is

not an awkward mismatch but a metaphysical conceit worthy of

John Donne. All of Ulysses allegorizes Homer's epic as

a journey of the human mind. Ithaca consummates this

reinterpretation, ending the saga of sadness, alienation, and

longing on a note of intellectual mastery.