Like the tongue-twister featured in Singin' in the Rain

("Moses supposes his toeses are roses, but Moses supposes

erroneously"), some answers to the riddle were simply silly.

In Weep Some More, by musicologist Sigmund Spaeth,

Thornton found two of these nonsense answers in different

versions of Where Was Moses When the Light Went Out?,

a popular song which dated back at least as far as 1878, 26

years before Bloom's revelation. According to one version,

Moses was "Down the cellar, eating sauerkraut." The other

"implied that Moses had suffered the inferior extremity of his

shirt to escape from its confinement"—i.e., he was "Down in

the cellar with his shirt tail out."

Given Bloom's fondness for songs, ad jingles, and

nursery-style rhymes, his head may well have become infected

with such catchy pop-culture nonsense. But locating a couple

of these rhymes as Thornton does—and Gifford and Slote follow

his lead—sheds no light whatsoever on the Ithaca passage.

The relevant idea, implied by both verses putting Moses in the

cellar, is that he was in the dark. This straightforward

answer to the riddle is not nonsensical, but it is mildly

absurd: it embodies the "Duh!" (or Homeric "D'oh!") principle

of realizing the obvious.

In a personal communication, Doug Pope observes that Joyce

might have known of a literary precedent for Bloom's answer:

the same solution is mentioned in The Adventures of

Huckleberry Finn, first published in the UK in 1884. In

chapter 17, when Huck appears at the front door of a family's

cabin in the dead of night, they cautiously take him in,

ascertain that he is not a member of the murderous Shepherdson

clan with whom they are feuding, and entrust him to the

keeping of their son Buck, who "looked about as old as

me—thirteen or fourteen or along there." Buck takes Huck

upstairs to his room, gives him some clothes, brags about some

small creatures he caught in the woods yesterday, "and he

asked me where Moses was when the candle went out." Huck

is flummoxed by the riddle, though his presence in a

candle-lit cabin in the woods might well have suggested an

answer, and Buck encourages him: “But you can guess, can’t

you?” Finally, Buck supplies the answer himself: “Why, he was

in the dark! That’s where he was!”

Riddles like this, stock in trade for 13-year-old boys,

deliver a stupidly literal answer that seems head-slappingly

obvious only in retrospect. Bloom is much older, and he has

discovered the answer himself, but since his Eureka! moment

comes only after 30 years of on-again, off-again pondering, he

appears to no better advantage than the uncharacteristically

slow-witted Huck. Joyce's allusion to the American novel, if

such it is (and "candle" is convincingly specific!),

shows him playfully making Bloom the victim of a joke.

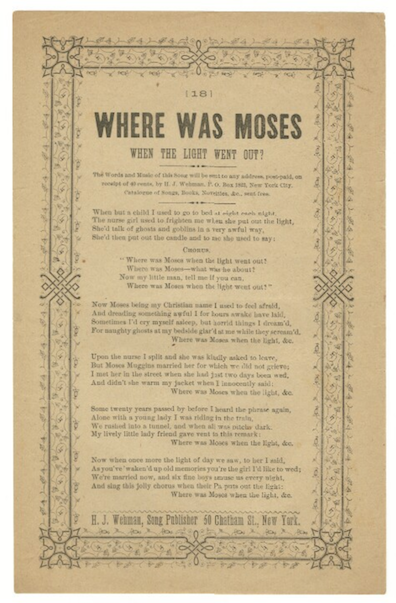

But in some other variants of Where Was Moses When the

Light Went Out?, the same implied answer, "in the dark,"

assumed more suggestive meanings. Instead of asking a boy to

solve a riddle, the version whose lyrics are reproduced at the

top of this note exploited his terrors and excited his early

adolescent desires. In this song Moses is the singer's

"christian name," and he recalls how a "nurse girl" who puts

him to bed at night used to terrify him by narrating stories

"of ghosts and goblins in a very awful way," then putting out

the light and asking him where Moses was when the light went

out. The poor boy would lie awake for hours after this

sadistic manipulation. Eventually, though, he gets his own

back: the nurse is fired, and after hearing that she has

married a man named Moses Muggins he finds her in the street

two days after the wedding and "innocently" asks her where

Moses was when the light went out.

His sly revenge births further sexual innuendo 20 years later

when a train on which he is riding enters a pitch-black

tunnel, prompting a young woman sitting near him to ask where

Moses was when the light went out. The song does not say

whether she asks this question knowing what trains entering

dark tunnels could symbolize, but its description of her as

"lively" suggests that she does. As for the young man, hearing

the Moses riddle again revives his cherished sadomasochistic

memory of the servant girl. As they emerge from the tunnel he

says to this new woman, "As you've waken'd up old memories

you're the girl I'd like to wed." Singing the song years in

the future, he says that he did marry the girl and they have

produced six fine sons, who, when their father puts out the

light at bedtime, sing, Where was Moses when the light went

out?

If Joyce wanted his readers to call to mind some such version

of the Victorian-era song, then Bloom's imagination of a Jew

(his favorite Jew) finding himself in the dark brings with it

an air of dread spiked with sexual excitement. These emotions

are by no means irrelevant to Bloom's situation as he stands

in his parlor, getting up the nerve to crawl into bed with the

woman who has deliberately subjected him to sexual humiliation

on June 16. Is he a candle whose wick has been snuffed? Or is

he being called to plunge back into the dark tunnel? Penelope

will show that Molly is thinking both thoughts, and looking

for Bloom to decide which version of the story will come to

pass.

Both the parlor song and Twain's story feature a young man

placed in a position of awkward ignorance and challenged to

find his way out. It is possible to hold both in mind while

reading the Q & A in Ithaca. Like Huck, Bloom has

set himself the task of solving a riddle, and the answer is

revealed by his present situation: he has just turned out the

light. But the blackness in which he is standing also evokes

perils, as it does for the terrified boy in the song. Alarmed

by the possibility that his marriage may be coming to an end,

and keenly aware of his sexual connection to Molly, Bloom

inherits both the boy-man's fears and his glimpses of sexual

maturity. The allusion suggests that he may yet triumph over

his ghosts and goblins by acting the part of a man. A silly

song suggests the possibility of something heroic in him:

overcoming sexual self-doubt.