In the

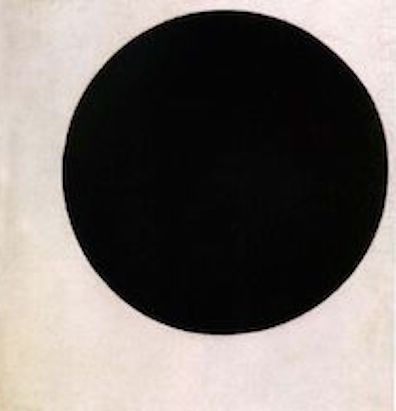

Rosenbach manuscript, Joyce wrote at the end of Ithaca, "La réponse à la dernière demande est un

point"—the answer to the final question is a

point. This may sound absurd, but in French, the

language of the printers whom Joyce was addressing, point can

refer to a period or full stop. He wanted the

typesetters to place this common symbol after the

question "Where?" as an

answer to it. On successive proofs he specified that the

point should be "bien visible"—clearly

visible—and then that "le point doit être plus visible," the

point must be more visible. Perhaps because the

typesetters could find no good way of fulfilling his

request with the characters in their trays, what he got

in the first edition was a clearly visible black square.

Some

later editions have further frustrated the author's

intent by omitting the mark entirely, and even those

that print it do not agree on how large it should be.

The Random House editions from 1934 to 1961 and the

final Odyssey Press edition of 1939 employ a big bold

blot that is slightly less tall than a standard capital

letter in the text. Some people have thought this too

big. Among them, apparently, is Hans Walter Gabler,

whose Critical

Edition of 1984 featured a much smaller

period. In his critical review, "Errors of Execution in

the 1984 Ulysses," Studies in the Novel 22

(Summer 1990): 243-49, John Kidd objected, sensibly

pointing out that what the Gabler team supplied is "far

smaller than even the intermediate dot Joyce had

insisted should be made more visible" (248). In his Corrected Text of

1986 Gabler made the dot a bit larger, but even this

revised version offers (ahem!) a pointed alternative to

the aesthetically satisfying large dot of the earlier

editions.

If

the proper size of the black dot is uncertain,

the significance that Joyce intended for it to

convey is more so. Many equivalents have been

proposed, but before jumping into any of them

readers may want to ask how the text prompts

such speculations.

A simple but productive starting point is to

recognize that the question "Where?" in the last

paragraph is nothing new: the previous six

paragraphs have all pursued a line of interrogation

that could broadly be called geographical or

spatial. First, the narrative asks about the

"directions" in which the Bloom's two bodies are

lying in bed. Then it addresses those bodies'

inertial states of "rest or motion"—relatively

stationary, but absolutely swinging through

interplanetary space in huge swift arcs. Next it

analyzes the bodies' "postures": how their parts are

arranged on the bed. Finally

it observes that Bloom is "Weary" because "He

has travelled" throughout Dublin during the day

and now (in a variation on the earlier "rest or

motion") "He rests." There is also a suggestion

of returning to the "Womb."

The

womb is certainly a place, but no one can return to

it after birth—though the picture of Bloom as "the

childman weary, the manchild in the womb" suggests

that he would like to do so. This detail of the

third and fourth paragraphs is followed, in the

fifth, by another place that no one can physically

access. As Bloom starts to drift off to sleep his

mind reels through a childish series of sound

associations prompted by "Sinbad the Sailor,"

suggesting that his day's Odyssean journey is giving

way to a nighttime journey into fantastical Arabian

places. In the sixth paragraph the strange question

"When?" makes even time a

kind of place. "Going to dark bed" (a properly

spatial kind of movement) takes Bloom into "the

night of the bed," and at the end of the sentence

Sinbad's (Darkinbad's) voyage into darkness seems to

be followed by the Sailor's (Brightdayler's) journey

into the new day. It is quite late, and earlier in

the chapter Bloom has recalled once staying up all

night and seeing the sun rise. His sleepy,

half-comprehensible thoughts here suggest that he is

looking past his voyage into the darkness with

anticipations of June 17.

These

six sections of Ithaca all

address travel: around Dublin, back home, into bed, into

the womb, into a fantasized Arabia, into the next day.

The chapter's final question, then, is merely a

culmination of the six that come before it. If the

answer to the question is a black dot, then it too must

be a place, at least in the loose sense that the Womb,

Sinbad, and June 17 are places to which the mind can

travel. What is this place? One interpretation seems

obvious: Bloom is traveling into the black unknown of

sleep. That he embarks on the journey accompanied by

Sinbad and his alliterative companions says something

about the places he may visit in his dreams. The posture

that he adopts as he drifts off—"the childman weary, the

manchild in the womb"—also suggests that loss of

consciousness is somehow taking him back to origins—to

childhood and thence to that place from which all life

journeys begin.

The

dot can certainly be visualized as the black

hole in a woman's belly, and Joyce seems also to

be inviting his readers to connect it to the "roc's auk's egg"

of the penultimate paragraph. Eggs implant

themselves in wombs to bring forth new life, but

Molly's womb has never been fertilized since the

untimely death of the couple's infant child. The

novel asks whether the turmoil surrounding the

affair with Boylan (he has left her "big with

seed") might bring about salutary change in this

sterile sexual relationship, and the beginning

of the next chapter shows Molly thinking about

Bloom's changed behavior: "Yes because he never

did a thing like that before as ask to get his

breakfast in bed with a couple of

eggs."

One may note here not only the insistent return

to eggs but also a reprise of the motif of day

following night. Concerns

from the end of Ithaca, funneled

through the black dot, carry over to the

beginning of Penelope.

Wombs

and eggs infuse interpersonal, sexual concerns

into Bloom's experience of going to sleep.

Another textual detail points to more purely

intellectual registers of experience. Calling the

roc's egg "square round"

recalls the thought of geometers squaring the circle

that occurs to Dante in the final lines of the Divine Comedy as

he gazes up into the capacious "circlings" of the

triune godhead. The simile characterizes Dante's

rational attempts to make sense of the frustratingly

transcendent mystery of how God can be incarnate.

Like the geometers, Dante fails to make rational

sense of the Incarnation and the Trinity, but then

he finds rationality and selfhood extinguished in a

blaze of mystical insight that grants what he has

sought: access to the source of all being, the mind

of God.

The

"Where?" of Ithaca,

by contrast, is the mind of a human being

leaving the daylight world and entering the

state of sleep. In an inversion typical of

Joyce's Dantean allusions, medieval religiosity

gives way to modern secularity, and

light-flooded circles become a dark one. Sleep

does, however, bear some resemblance to mystical

vision, because it temporarily obliterates

selfhood and reason: thinking strangely morphs

into dreaming, and consciousness is lost only

to be reborn at waking.

Read this way, the black dot suggests both

shrinking and expansion. As a mere point,

printed just large enough to be different from

other full stops, it suggests the contraction of

consciousness, like the shrinking circle of

light on the screen when the TVs of the 1950s

and 60s were turned off. Made larger, it looks

like a hole bored through the page, a tunnel to

something on the opposite side of normal

perception.

Bloom's

incoherent half-dreaming thoughts of Sinbad and the

roc's egg flow into the black dot like water down a

drainhole, to reappear god knows where. For him this

is the end of the story, but for Joyce it was only

the beginning. By mapping the Dantean trope of

transcending rationality onto the landscape of sleep

he began the process of writing Finnegans Wake. The

two half-crazy swirling Sinbad sentences feel like

anticipations of Joyce's final work, and "Finbad the Failer"

feels like a nickname for HCE.

These

thoughts are my own, but versions

of many of them have occurred to many other people

. In an article that surveys some of the ways in which

Joyce critics have responded to the strange symbol—"The

Full Stop at the end of Ithaca: Thirteen Ways—and Then

Some—of Looking at a Black Dot," Joyce Studies Annual 7

(Summer 1996): 125-44—Austin Briggs takes up the idea of

the dot as a hole in the text. Quoting from The Robber Bride, where

Margaret Atwood reflects that the period after "The End"

suggests "A pinprick in the paper: you could put your

eye to it and see through, to the other side, to the

beginning of something else," Briggs observes that the

full stop in written texts has sometimes been termed a punctus or a

"prick": a puncture mark, more an aperture than a stop,

a portal of discovery for readers to gaze through (128).

Robert Martin Adams, he notes, saw the dot at the end of

Ithaca as a

"black hole" through which Joyce's mind passed and "it

is never a daylight mind again" (128). Adams too was

thinking of Finnegans Wake.

Texts that enlarge the large dot evoke this alternate

reality, but others eliminate it entirely, and Briggs

notes that there is a kind of logic to this choice too:

"The geometer's point has a definite position but no

shape or size or extension. How boldly the mark is

inscribed on Joyce's page may therefore be in a sense

irrelevant, for all geometric points are equally

no-size" (135).

Early

on, the article observes that Ulysses and Finnegans Wake

perpetually raise "the distinction between the visible

and the audible text" (126). Both novels demand to be

read aloud, but how does one bring a black dot to life?

Anthony Burgess and Richard Madtes suppose that it could

be performed as a snoring sound, the snores of the

somnolent Bloom silencing once and for all the

mynah-bird rational loquacity of Ithaca's

narrator. Many critics have responded more abstractly to

the visual implications of the symbol. C. H. Peake and

Harold Baker suppose, in slightly different ways, that

narration, grammar, and language itself are falling

asleep, dissolving into mere ink on a page. Others have

intuited a sense of conclusion similar to the sense of

conclusion at the end of a sentence, but grander. In a

letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver in early October 1921,

Joyce wrote that "Ithaca is in

reality the end as Penelope has

no beginning, middle or end." In this framework, the

outsized period may signal the true end of the novel,

its "emphatic stop" to male consciousness succeeded by "the

virtually non-stop 'female monologue'" of the final

chapter (129). (By that logic, Briggs cogently observes,

there probably should not be a period after Molly's

final "Yes," the ending left unpunctuated just as in Finnegans Wake.)

In

his Ulysses

Annotated Don

Gifford offers a particularly ambitious but also

tenuous version of the view that the black dot

serves as a mark of formal conclusion. Gifford

argues that the dramatically large capital letters

that the editors of the 1934 Random House text gave

to the initial words of the novel's three sections—"Stately,"

"Mr,"

and "Preparatory"—suggest

the Subject, Middle, and Predicate of a medieval

syllogism (as well as the names of the three

protagonists, Stephen, Molly, and Poldy). The large

period at the end of Ithaca,

then, is equivalent to the QED that declares a proof

to have been completed. Although some people

commenting on the novel still refer to this claim,

it has fallen into general disrepute, not least

because there is no evidence that the large capital

letters were Joyce's idea. (One may also note, in passing,

that in an interpretation of this sort the dot

has ceased to function in any way as an answer

to the question "Where?")

Some critics, while acknowledging that an outsized

period may convey a sense of conclusion, go so far

as to read it ironically. Karen Lawrence, Briggs

notes, regards it as a mere "parody of closure"

(130), and indeed Joyce's fictions do regularly

subvert such expectations. Briggs observes that "The

'pointless' stories of Dubliners do

not 'end' as stories were once expected to, and one,

'Counterparts,' stops in mid-sentence. Writing to

Harriet Shaw Weaver in 1917, Joyce directed that the

words 'The End' be deleted from a new edition of A Portrait

underway" (130). Finnegans Wake, of

course, makes beginnings and endings

indistinguishable.

In his

article Briggs surveys a bewildering variety of other

critical interpretations of the black dot: it is Molly's

anus, or a "hole" suggesting equally anus or vagina, or

a "period" in the menstrual sense, or the head of a

nail, or the contraction of a comet, or the earth seen

from distant space, or the "pinprick" that is a star, or

an astronomical black hole, or Bloom's triumphant

squaring of the circle, or Bloom's nothingness, or "the

now, the here" of Bloom's life before the novel plunges

into the timelessness and everywhereness of Molly's

monologue, or an isolated point transcending time and

space, or an egglike encapsulation of the infinite

possibilities held within a single moment, or the womb

of time from which a new day will emerge, or the

daybreak itself (the French pointe du jour). Some

of these readings contradict others and

some are less helpful to baffled readers than others

, but their sheer number may serve as a warning not to

expect a single, clear, universally agreed-upon

significance in the symbol.

Here

once again there are intimations of Finnegans Wake,

with its innumerable meanings. Periodically quoting

from it, Briggs suggests how strongly Joyce's

interest in the period or full stop carried over

into the later novel: "Finishthere. Punct" (17.23);

"Fillstup" (20.13); "false step" (210.26); "Fools

top" (222.23); "Fool step" (370.13); "Fill stap"

(595.32); "fullstoppers and semicolonials" (152.16).

The idea of the punctuation mark is most richly

addressed in the chapter (1.5) devoted to ALP's

letter—a figure for literature itself. Periods or

full stops were not used in many ancient

manuscripts, and the Letter has been written in this

manner, flowing on from word to endless word like

Molly's monologue. However, it has apparently been

pierced by the tines of a fork, producing four kinds

of punctuation marks:

it showed no signs of punctuation of any

sort. Yet on holding the verso against a lit rush this

new book of Morses responded most remarkably to the

silent query of our world's oldest light and its recto

let out the piquant fact that it was but pierced

butnot punctured (in the university sense of the term)

by numerous stabs and foliated gashes made by a

pronged instrument. These paper wounds, four in type,

were gradually and correctly understood to mean stop,

please stop, do please stop, and O do please stop

respectively.... (123.31-124.5).

Joyce is having a lot of fun here

(as the four "paper wounds" are translated, one

can almost hear the text crying out not to be

stabbed any more), but, as the language of verso,

recto, and "university sense" suggests, he also

seems to be conducting a paleographical

investigation. In the 3rd century BCE,

Aristophanes of Byzantium developed an influential

system of punctuation in which a hypostigme

or dot placed low on the line of characters

signaled a brief pause, as a comma does, a dot at

the vertical midpoint of the characters called for

a longer pause as semicolons do now, and a dot

high on the line indicated what would eventually

come to be called a period or full stop. Low dot?

Stop! Middle dot? Please stop! High dot? O do

please stop! Perhaps some later grammarian added a

fourth symbol?